Civic-Minded and Morally-Guided Practices

Jeffrey Moser: Dear artists, welcome to another episode of the From the Ground Up Podcast produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. I'm your host, editor and producer Jeffrey Moser recording from the ancestral homelands of Potawatomi, Ho-Chunk and Menominee homelands, now known as Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

These episodes are shared digitally to the internet. Let's take a moment to consider the legacy of colonization embedded in the technology structure and ways of thinking that we use every day. We are using equipment and high-speed internet not available in many indigenous communities, even the technologies that are central to much of the work we make, leaves a significant carbon footprint contributing to climate change that disproportionately affects indigenous people worldwide. I invite you to join me in acknowledging all this as well as our shared responsibility to make good of this time, and for each of us to consider our roles in reconciliation, decolonization, and allyship.

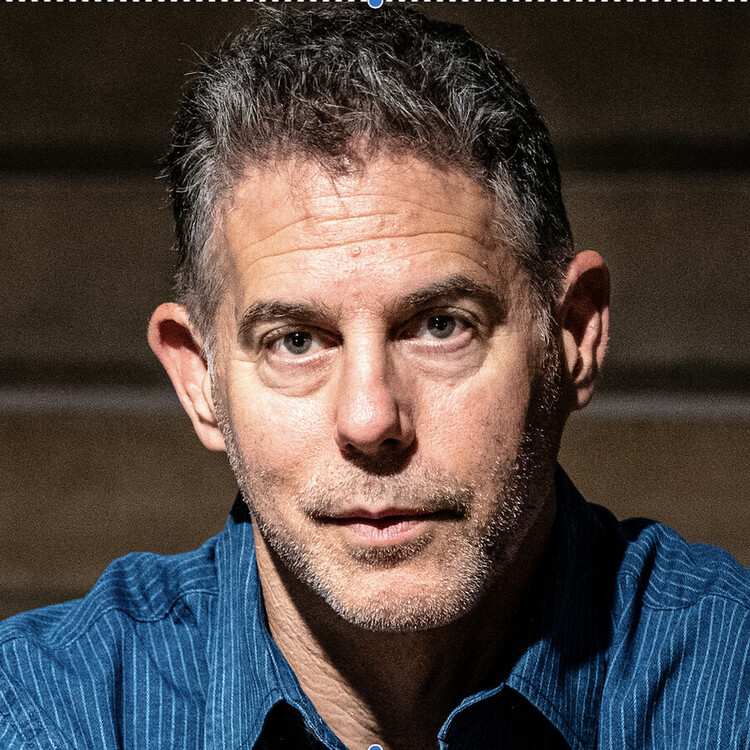

I come at you each week and say that I'm really excited to share this episode with you. At the risk of sounding redundant, I am really excited to share this one with you. Today's guest, Michael Rohd, has influenced my work in so many ways. In my first job while I was exiting undergrad, I used his book of exercises, Theatre for Community Conflict and Dialogue. Little did I know that I would get the chance to study with him years later. I wanted to talk to Michael, because I've always seen him as someone who's at the front edge of the ever-evolving state of ensemble-based theatre.

At one Network of Ensemble Theaters conference in Chicago, I heard him ask an auditorium of ensemble practitioners, “What is ensemble?” And the answers were vibrant and expressive and expansive. And most importantly, no two were the same because it's clear that we as ensemble creators, get to define what we do and how we do it in amazing ways. We'll get to hear what he thinks ensemble is now and where it might be going. We kick off our conversation by talking about definitions and how it helps his practice. And we dig into how shared leadership is present in two organizations he's affiliated with: both the Center for Performance and Civic Practice in Phoenix, Arizona, where he is an artist for civic imagination and founding artist, as well as in his new role as ensemble member at Sojourn Theatre in Portland, Oregon. Michael and I held a Zoom call on September 27, 2021. He joined me from Phoenix, Arizona, the ancestral lands of the Akimel O'odham and Pee Posh peoples. Enjoy.

Michael Rohd: Hello there, how are you, sir?

Jeffrey: I am so good. So good to see you. This is such a pleasure for me on so many levels.

Michael: It's good to see you too.

Jeffrey: Thank you so much for being here. I really appreciate your time. I love that our paths have crossed so many times and I can really truly say that I appreciate knowing you. I have never been in a room without you defining something. So I was watching the Clark Forum interview that you had a while ago. And one thing you said that really stuck with me was that artists keep, maintain, and transform meaning. And whereas I had always thought about theatre as a means of a metaphor in which to see things differently or to create things differently so that an audience can encounter them in a different way, but what you provide is this framework as artist as an advocate, artist as a creator, as a changer—changing, transforming the audience. And I'm wondering, where does this insight come from to constantly find ways to define things?

Michael: It's a very interesting place to start. First, it's nice to see you, and I love that our paths have crossed off and on as well. And I'm really appreciative to get the chance to talk with you in this space because I really like conversation; I like dialogue a lot. And when you describe it that way, it is very interesting because I feel like we are in a moment... I generally believe in questions more than answers as an artist and an as educator and as a person, I'm more interested in questions than answers. But you're right, that I also have spent energy trying to define ideas or find terms that I think can be useful. And I'm hoping that that impulse comes not from wanting to control meaning or conversation—which your assessment demands that I interrogate my own history around language in relation to whiteness and privilege and patriarchy and colonialism, all these things that are real and that have a lot to do with how language is deployed to control. So I'm going to think about that after this conversation.

I know that, for me, I am interested in definitions because I feel like when we are often working collaboratively, either in a thought ideation space or a problem-solving space or a co-creation space, that we sometimes use terms or words as if we all mean the same thing when we use them, and I find that we often don't. So sometimes I guess in a room I'll propose that, and sometimes in writing or in a project, I'll actually suggest like, “Hey, here's a word that I think could be useful.” For me, ideas like civic practice or now, civic imagination, have become proposals to colleagues and maybe to fields in general to say, “I think there's something that's going on that we're not naming or making connections amidst. So here's some verbiage to maybe help us think about this work in relation to itself.”

Not so people will, in an Orthodox way, commit to describing things as I insist they be described, but rather as an offering so we have some table to meet at around some definition that we can then push and pull at and tug at or break open or get rid of, which certainly happens as well. So I think that's why I'm drawn to it. Like if you ask questions in a room and people answer with a word but mean different things, I don't think the conversation is that satisfying or useful. So it's about how do we find frameworks and ideas and words that help us come together. Definition's not in a scholarly notion of this must now be monolithically a meaning that is shared, but here is hopefully an on-ramp to more discourse that's productive across lots of different perspectives.

Jeffrey: One thing I really appreciate about it is that it has always become a magnet. And then the ideas cling to one of those definitions as a magnet. So we have a pillar or a cornerstone that we can then work from for the rest of the process. So it allows artists to be better artists, because then we name something, it seems as though that would also be useful in civic practice or civic imagination as you call it.

Michael: Yeah. Certainly, for me, civic practice as an idea was a way of framing a batch of work that I thought was getting collected under the social practice umbrella. And that actually had some useful distinctions to note. And for me, civic imagination is something that I'm trying to move outside of the art ecosystem into the local government ecosystem and starting to frame that idea these days. So yeah, I find it helpful to invite folks into a conversation.

Jeffrey: We are able to hold in our heads right now multiple truths or the idea of multiple truths. Is there a way for us to define or find commonality between those common truths through defining, or have you found that in your practice at all?

Michael: I think the big questions right now—as artists but also maybe as members of communities of places and coming from our own unique and particular positionalities—is how do we build a healthier we? How do we build a stronger we? So to build a stronger we, it means to make sure that there is equitable access to the commons, the public good capital, all the different things that we need access to. It also means that singular definitions are probably less and less—this is slightly contradicting what I said a couple minutes ago—but singular definitions are less and less useful because what's important is that anybody who brings interest or lived experience or desire to a conversation should be able to name the terms upon which they enter the conversation. Otherwise, somebody else's idea, mine or anyone else's, can get in the way of everybody being able to collectively bring wisdom and make change together.

If the question is: Can multiple truths live alongside each other? If they can't, how do we live together? Because we have multiple truths. In my household, we have multiple truths. On my street, in my neighborhood, in my city, in my state, in my nation, in this world, we hold multiple truths. They're organized around so many different principles, faith, ideology, politics, background, family of origin. So we better be able to live with different truths. And then how do we make spaces as artists in process and then with audiences and participants and spectators for different truths to be productive and healthy and positive?

Jeffrey: Can you help me define the moment of ensemble-based and collaboratively creative work that's happening now, the moment that we're in?

Michael: It's a good question. I think we're in a really interesting moment. I think that the notion of ensemble, the idea of ensemble, the practice of it, people working together purposefully and intentionally to make things together, be those ideas or change or art or performance, whatever it is. I think people are trying to figure that out all over. People are trying to figure that out in institutions, people are trying to figure that out in government, people are trying to figure that out in change movements. So in the theatre world, I think we're in a moment where ensemble is recognized as powerfully as it ever has been. But I also think we're in this amazing interrogation of ensemble, like what should leadership mean in ensemble? What has it meant historically? What does it need to mean now in this multiple pandemic moment—including more legible than ever social justice reckonings, racial justice reckonings? What does shared leadership look like? What does it look like to make decisions as a body of people in an equitable way?

I think the moment that we're in is both like a step forward for ensemble practice within and beyond the arts ecosystem, but I also think it's a moment that's demanding real attention to what we have enacted when we have said ensemble, historically, who's had access, who hasn't? Who's been included, who hasn't? Who's been leading, who hasn't? How many artistic directors, myself included, have existed in an ensemble framework but have also benefited from historical hierarchical practices within our field? So I think we're at a really interesting, complicated moment of opportunity, but also demanding real self-reflection and analysis, I think.

Jeffrey: Relating to what you had said, I always thought of an ensemble work and collaboratively creative work as being more inclusive and more equitable and less hierarchical, rather egalitarian of sorts yet retaining democracy of a certain amount. But I'm wondering if you could talk about that and the decision for Sojourn to go that route of development of a leadership board.

Michael: Yeah, so we call it a leadership body. And basically on July 1, this past July 2021, we formally transitioned from being an artistic director–led company, and up until that point, I had been the founding and ongoing artistic director to now a leadership body led. And the leadership body of Sojourn Theatre consists of Bobby Bermea, Jamie Rea, Nik Zaleski, and Courtney Davis. So I'm now an ensemble member, which is awesome to be an ensemble member amidst this wonderful group of artists. We started work about fourteen months before that announcement. So spring 2020 was when we started that journey. And I hope you get an opportunity to talk with the leadership bodies, some members of it on here, because that would be a really good conversation.

I can speak for myself. For me, I was feeling that twenty years was plenty long for a single artistic director to be helping guide and shape the vision of any theatre, and certainly an ensemble and certainly ours. So I approached the company about what a transition might look like. And we all agreed as a company and began a process of exploring that. And I think that we were really thinking, and I was thinking, that for a company to continue to change and evolve and be of the times that it is in and to develop a vision for its future, it needs a different kind of leadership and a different imagination that my fifty-four-year-old white male imagination, it is not necessarily the appropriate one to be guiding this company—or any company—into the future at this moment. There are other voices and other models to do that in a probably more dynamic and visionary way that's connected to the company's interest in where we are as a world right now.

So we worked on that. And the company was incredible and had an incredible set of conversations and different company members facilitated it. And we went through it. I believe we went through it with love and a lot of, I think, rigor and attention. And I think folks were very... I am very happy and excited about where we are now. And I hope you get a chance to talk to others about that journey. And different ensembles decide for themselves what the moment of transition and leadership is, but to me, as Nik Zaleski, one of the new leadership body members said, I think in a statement she put in the press release, she said, “We are thrilled to not just enact principles of equitable democracy in the ways that we work in our creative process, but to enact them in our organizational model and structure and decision-making process.” And I think that's a really good statement.

Jeffrey: Beyond leadership and decision-making, what work do collaborative creators and ensembles need to be doing better?

Michael: Well, I don't think I can presume to say what anybody else should be doing better. I think I can say that whatever an ensemble takes as its mission, like what is its purpose as a group of artists? What does an ensemble come together around? Then I think we just all need to be attentive to how we are listening within our circle, how we're listening to each other, how we're making space for everyone in that circle to have agency and to have a vision that reflects everyone in that space, and how are we paying attention to the relationship between our mission and our values, and who is in the circle? Are we in circle with who we need to be to manifest the vision and mission that we have set out? Do we need to expand our circle?

And then there's a circle of our ensemble, but then who are our stakeholders? Who's our community? Who are we in service to? And how are those human beings in circle with us or in another ring of circle? And what's the process by which the ensemble circle and that ring, that circle, is actually in an ongoing dialogue? So I think to me, at this moment, I just care about all of us considering who we hold circle with, how we hold it in healthy, equitable, and just ways and how we connect purpose to action. Everything's a moral document. Our budget's a moral document, our mission's a moral document, our programming choices, our moral choices. What we prioritize is reflected in all those things, what we choose to produce, what we choose to develop, who we commit to, how we spend our energy, how we engage with folks not in the core circle. And all those choices represent a manifestation of our purpose—or they don't. And I just think all of our attention just needs to be on the relationship of those things, choices, priorities, purpose, relationships and probably for many of us, equity and justice and change being centered in all those conversations.

Jeffrey: With your leadership at CPCP, Center for Performance and Civic Practice—

Michael: Has also transitioned, right?

Jeffrey: Yes. Yeah, do you want to speak to that at all?

Michael: Sure. There were initially three of us, then five of us, and then three of us, over the years, the past decade, and then about a year—similar to the Sojourn timeline—Shannon Scrofano, Rebecca Martinez, and I were co-leading and began the process of relationship building, deeper relationships with seven other artist-organizers that we'd worked with around the country. And over the course of the past year, that group has redesigned CPCP organizational model. And we are now a collective of ten. And that group of ten now makes all organizational decisions for the company from spending, to what activities we take on, to what programming we do, to who does what gigs. And one in a collective of ten, no longer a leader in that organization either, that's been also a great process with a tremendous group of folks—some theatre practitioners, some not. If Sojourn is a leadership body of four representing a larger company of fifteen, of which I'm a part of, CPCP is a collective of ten.

Jeffrey: That's really cool. I don't think I had heard all those parts and pieces yet though. Thank you for sharing that. That's so cool. Through that transition, and as you go forward with it, do you think that social justice work or more civic-minded work, do you think that it's on the rise or getting more attention paid to it right now?

Michael: Yeah, it's an interesting question. I think there are probably researchers and scholars who spend a lot of time and could answer that with some actual data. Obviously social justice work, the work of change, is not remotely new. It's been going on in this nation and around the world always. Artists have also always been engaged in social justice and change work. I think in the last half decade, and certainly particularly in the last year, the institutions, which we think of as historically dominant in the nonprofit industrial complex—whether you're talking about theatre, museums, dance, visual art, all of those—have started to narrate publicly the work of social justice in their respective fields and buildings far more actively and quickly than ever before. And some of that is folks using the opportunity to push what's always been central to their values even further, and part of it is people jumping on the trend bandwagon, I think, and wanting to be a part of that and not miss out on the attention and the funding.

Within all of that, there are historically—in Black Indigenous and people of color communities, our queer communities, our disability communities—there have been people doing that work in those fields and in their own spaces and in their own organizations but not given the microphone, not amplified into a mainstream culture or media context, but have been there the whole time doing the work. How do we make certain that the folks who've been doing the work do not get left behind resource-wise or attention-wise or leadership-wise as larger institutions come into the fold more and more?

So I think that's a really important thing to note as we talk about the scale of social justice work right now. I also think young people coming... I don't know. I graduated college in 1989. And I can say as an absolutely true data point that the number of people coming out in that time of traditional arts programs—I said I can say, I believe this to be true—that there were not nearly as many young artists at that point entering the field with social justice intentions central to their work in relation to the number of young people I encounter in undergrad or in community now for whom that is central to their work and their purpose. And I think that certainly states the influence that a lot of folks have had in their fields over the decades, but it also is about how important change is to young people—across fields, but certainly in the arts as well these days.

Jeffrey: I want to change gears just a little bit and talk about content a little bit. So much of your work is participatory, if not all—all that I have seen. And then how do you know that the content that you've created has made a difference in an individual or in the community that you share it with?

Michael: Yeah. You're talking about measurement or impact? I think you decide on the front end—you and whatever stakeholders and collaborators are at the core of the project—how are you going to define success? You might define success by just believing that if you get the folks in the room that you hope come into the room that, that's success. And what their experience is, you can't control, don't want to control, and don't want to assess. Or you might decide, actually the success of this project is, do we expand folks' perspectives on a certain critical dialogue in public conversation right now? Those are different success criteria we figure out, and then it iterates, of course, over the course of a process, what will success mean to us? What will it mean to partners? What will it mean to collaborators? What will it mean to those we work with?

And then, okay, what questions do we have to ask to who at what point or points to discover if we've been successful? It's very infrequent that I want to hang the success of an art space project on whether an individual's mind was changed. I am generally more interested in reflection, sometimes action—that doesn't have to require a mind change, but something happened. I'm interested in the thousand dollars going somewhere as a result of the project. I'm interested in new relationships between urban and rural residents. I'm interested in strangers who'd never met having an experience of talking about challenging issues with each other and having that remain loving and respectful, even when uncomfortable.

And then hopefully, those muscles get built and continue to exist in their experience in the world. But then again, there's Witness Our Schools from back in like ’04, ’05, where success meant, are useful dialogues happening in all these towns around Oregon, where we go with local political leaders and citizens who would usually not get to talk to them? Is data being brought to the state legislature that they wouldn't get other than how they're getting it through this project? Are voices being heard on the floor of the Capitol that wouldn't be heard otherwise? So it really is different for each project, but it starts with what will success mean?

Jeffrey: And typically, you have some facilitation around each project as well, is that correct?

Michael: It depends on the project. Some shows, some forms need a layer of facilitation or hosting and some don't. I guess I haven't done a lot lately that has felt more purely presentational. I have an exhibit in a museum right now. Part of an Agnes Gund fund for justice supported art museum exhibit out here in Arizona, around mass incarceration and the history of mass incarceration. And I'm one of twelve artists in the exhibit in my portion is actually participatory; it's using the architecture of the museum as a site for text and then interactive experience with audience members. So, there's no facilitation; just the instructions are all a part of the audience journey.

Jeffrey: I have the privilege of being your note taker at the Double Edge Art and Survival-

Michael: Yeah, Art & Survival. Yeah.

Jeffrey: ...event.

Michael: That was a while ago, right?

Jeffrey: That was a while ago. And you were facilitating a conversation, but I honestly remember this moment where it started out going the right way and then it took a turn and the folks on the call were no longer maybe serving the ideal of the nature of the topic anymore. And it became that they wanted artists to do something that would've served some propaganda rather than some community service or community regard. Which is all to say, I'm wondering how you deal with a facilitation moment that takes a turn where you end up having a morally challenging question in the middle of it, where you are now a focal point as a facilitator now having to navigate this conversation. I just remember your work in that moment being like... it was like listening to jazz. You ran with it, you framed it, and you had the conversation to address their issue, but also bringing it back around to meet us back where we continued.

Michael: Well, maybe a sideways way to get at that is I'm co-teaching a class right now with the amazing Dr. Maria Rosario Jackson. It's called Purpose, Collaboration, and Accountability. And we were talking about facilitation the other day with a group of grad students and talking about the work of listening and the work of presence. And in relation to being in a room that has a focal purpose, you have to know as a facilitator: Is your job to serve the group? Is your job to serve a particular action item that is supposed to be accomplished? Is your job to continue to try to take the group deeper into a conversation that we may not know what the outcome or output's going to be, but we're just supposed to go as far in and into discovery as we can?

So those are different things: serve the group's desires, push for deeper discovery, get to an accomplished action or solve a problem. I think for me, it's really important as a facilitator, also in a rehearsal space to understand what's my role? How does the room understand my role? What's the power dynamic at play here, both in terms of my assigned role, but also my positionality in relation to the beings here and whatever values have been articulated and whatever history we do or don't have?

And then the worst thing a facilitator can do is something can go off track and without attending to it, you can try to insist that things stay on track. So whatever you're describing as a positive improvisation, hopefully was like me listening, making sure to not write off what was contributed. Certainly as a facilitator, my job is to make that legible and help a group acknowledge, do repair work if necessary, and figure out how to go on if possible. But my job is not, I disagree with something and therefore I have to take it on just because it's not my idea. And I think listening and presence and the ability to flow and to shift gears and to make sure that the group can stay invested in where we're going, which means we're in this together, I have to attend to all of that as a facilitator or as a director or as an educator.

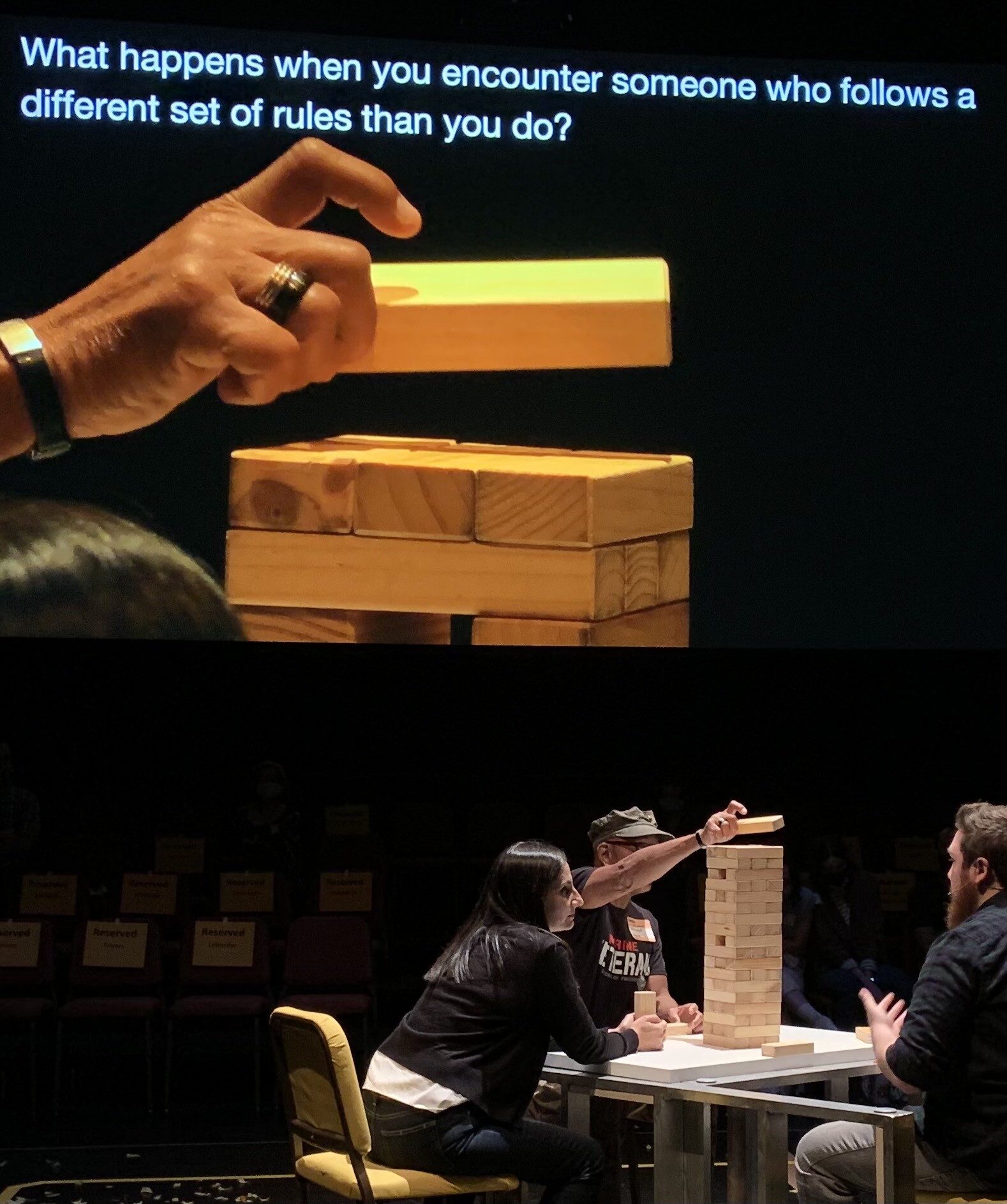

Sojourn Theatre’s Don’t Go. Photo by Halley Willcox. Led by: Rebecca Martínez, Michael Rohd, & Nik Zaleski. Featured in photo are Community Participant/members left to right. Four community participants/members of the Stranger Chorus who joined for this specific performance only, visible from left. Pardis Mahdavi, Ahmad Daniels, and with his back to us, Matthew Venrick. Lights by William KirkhamSets and Rabbit Friedrich. Projections by Sojourn Theatre.

Jeffrey: Sojourn has a history of being a collection of artists from across the country, correct? There's always been a national network of artists. How has the organization survived and thrived with that big picture of artists are all over the place—that idea?

Michael: It'd be fascinating to hear and important to hear other people's perspective on this in the company. For me, I think it's because we've kept projects going and those projects have allowed combinations of artists to come together and collaborate. We've also, for a number of years, done a yearly lab where everybody in the company comes together for a few days—often in Arizona, the past five years, pre-COVID—folks would come together, and we would work on new projects. Everybody could bring a new project and we'd make sessions to work on in each other's work. That's been a real continuation of our group health, I think, and then just multiple projects that bring different folks together. And folks go in and out of how active they are based on the season of life that they're in.

I think another thing is, I think we all say this over and over again, it's our artist family. I think everybody in this ensemble really loves working with each other and loves each other. And so I think people have made the choice again and again to stay connected. Now, it's worth noting that, although this is a transition moment in terms of policy, it'll be really great to see how things change in the coming months and years. Historically, nobody in the ensemble, myself included, is on salary except when they're working on a project. So we have an operations manager, who's not an ensemble member, who's on a partial salary and helps keep the virtual doors open, but nobody else is on regular salary for their work at Sojourn. Folks livelihoods comes from other places and then they work with Sojourn and that, of course, contributes to their livelihood each time they take on a project to work for a couple days or a week or a month or whatever it is. So that's the particular model that's allowed us, economically, to survive.

Jeffrey: How has Sojourn gone about finding partnerships with different regional presenters and theatres?

Michael: I think it's been a combination over the years of relationships different members of the company had with folks and then just being in conversation with them. Occasionally, folks reach out to us; occasionally, we reach out to folks. I think if you're asking about presenters and producers in the arts ecosystem, which are not always our hosts or producers, but when they are, it's mainly, I think the same as everyone else: relationships and reach outs.

Jeffrey: So when Sojourn does tour or does present a production in a different region, what do you give to those communities by touring or participating in those different markets outside of your home market?

Michael: I guess it depends on the project, right? Our show, How to End Poverty in 90 minutes (with 199 people you may or may not know), has happened in eight different states. And they were all different relationships. Like once it was a regional theatre, a couple times as a university, one time it was a presenter, another time it was a partnership between a regional theatre and the local United Way. So each time what we hope to bring or offer depends on who's invited us in.

But I think it's an interesting question. Sometimes we talk about hopefully trying to help build capacity for a certain art space to community development work through workshops, as well as production when we're there. Sometimes we talk about, or we're asked by a theatre, to help their audience consider other forms of performance so that, that theatre can expand the work that they share and that they make and produce. Sometimes in a university, we're asked to make the work part of the educational journey of folks on that campus, as well as help them engage with surrounding neighborhoods and communities because they're trying to do that more and more and they think a project of ours might help them do that. So it's different based on the host, the ask, the context.

Jeffrey: Do you think there's space for more of these partnerships and relationships with ensembles and presenting organizations?

Michael: Oh yeah. I think particularly because many ensembles have experience of working with local artists, often across disciplines, and many ensembles have experiences of engaging residents in places, more deeply than a traditional, maybe regional theatre model where it's just an audience or the occasional engagement event, I think ensembles are amazing resources for presenters, producers, learning environments with schools, universities, community colleges. Yeah, I think as many ensembles are learning or have been doing for a long time, residencies and relationships like that are really mutually beneficial, I think. And that's been my experience.

Jeffrey: What do you think needs to change for it to happen more frequently?

Michael: I would say it's advocacy and awareness work. I'm thinking about APAP, I'm thinking about Association for Theatre in Higher Education, I'm thinking about American Association of Theatre Educators—all these spaces, ensemble is not new in any of those spaces. So what are the other spaces where folks with leadership in educational environments, folks in arts presenting world, maybe have not been hearing a lot about ensemble that they could. I'll tell you one space I think that could be really powerful: community foundations and family foundations, who we have in just about every state and mid to large size city in the country, and they work often on local issues and needs and visions as they should, a lot of them don't necessarily belong to Grantmakers in the Arts, which is the service organization for philanthropists and foundations that do focus on arts.

So it's like, how do we get to those local foundations and help them understand how ensembles in their area could be really beneficial to their working community? That's one really specific place that I think advocacy and awareness could be really powerful. And then, of course, a lot of the work that I'm engaged in these days is around local municipal government in helping them understand how artists can be valuable contributors to public good—particularly around recovery outcomes. And ensembles can be really meaningful resources around recovery outcomes.

And there's funding, not just through the arts ecosystem but the local fiscal recovery funds that are out there in every city, county, state, and tribal government. That money can support ensembles working on non arch-related recovery outcomes with equity and justice centered in that work. So that's another space I think is really present right now.

Jeffrey: As we come out of COVID, not of this moment, what can artists be doing now as we emerge from COVID to prepare for more civically minded work?

Michael: Yeah, I think this is an incredible time to be alive, to be an artist, to be a practitioner, to be a member of the community. And I think that there's a lot of energy aimed at the potential for reimagining and redesigning systems at the civic level and at the institutional level. I think that some of it is lip service and some of it is very real. It's obviously very real coming from the direction of folks in change movements, in movements for justice. I think at the institutional and systemic level where it is folks saying, “Yeah, we need change to survive,” versus because they authentically believe that this needs to be a time of change.

But I think artists can be incredible collaborators in that reimagining and redesigning, whether that's a local organization that's talking about creating more equitable practices for working with residents in the place, it's a social service agency, a nonprofit, a municipal department, whether that's a university that's addressing its own history of white supremacy and colonialism in its relationship to the neighborhoods around it or the city where it resides, whether it's a local government and a commitment to a different transparency or work on a different civic engagement. I think artists can collaborate, can help ideate, can develop projects that align with these goals for change. So I think it's an awesome moment.

And then within the arts sector itself, as folks are trying to figure out how they actually want to be in the place where they are. I think arts institutions right now, get to ask the question in a very real way: Who do we serve? Who are we here for? And I think for some places, the answer is the same as it's always been. And for some, it's the same answer but a recognition that they maybe need to do more if that's their answer. And then for some, it's a new answer. So there's all these opportunities for artists, individual artists, as well as organization-based artists, to help in that thinking and help in that manifestation.

Jeffrey: What are you interested in finding out right now?

Michael: I'm interested in finding out right now, how we get folks in systems that affect all of our daily lived experiences, systems of governance, economic systems, nonprofit service ecosystems at the local level. How do we get the people who make up those institutions and gatekeep those institutions and lead those institutions to prioritize civic imagination as something that will help us build a stronger “we” and will help us more imaginatively solve significant problems that face residents in our communities—that face all of us? And then if we prioritize civic imagination, how can we recognize that we have artists practically on every block who can help us build that civic imagination in every place and in every community and in every neighborhood? So I'm interested in the advocacy work of doing that. And I'm interested in the practical work of how that can happen.

Jeffrey: What is a hurdle for CPCP that you wish you could eliminate at this point?

Michael: I don't think there are any hurdles for CPCP. I think CPCP is a collective of an amazing group of folks who, upon deciding what that group wants to accomplish and contribute in terms of a set of values centered in justice and equity and a center of purpose focused on transformational change, I think that group—which I'm fortunate to be a part of—can accomplish a lot. So I wouldn't know what to say to hurdles. I could say white supremacy and structural racism is a hurdle to doing that transformational change work, but I think that's a hurdle we all face. I don't think there's an external hurdle other than the hurdles that we all face to make a more just society.

Jeffrey: Anything else that you'd like to say that I haven't made space for you to address?

Michael: Tell me again, what's the center for you of the podcast series itself.

Jeffrey: And so yeah, the ultimate goal is for theatre practitioners to take that next step and figure out what they can do to do the next thing. For me, ultimately, I'd like to write on how all these organizations have come to be what they are and how they are—some collection or a passing collection of knowledge of ensemble-based theatres at this wave of collective collaboration. My next call this afternoon is actually with Alison Carey and Mildred Ruiz and Steven Sapp from Universes to talk about that reciprocal relationship of ensembles at a regional theatre. And so just understanding where you're coming from on in terms of the shared responsibility of the ensemble at the theatre at a presenting location is a big part of that conversation too.

So these are all interlocking. And actually part of the questions that I'm asking you too are interlocking into my bigger question, which I presume to be season three in terms of how civic practice and social justice work has been what has come out of Bread and Puppet and San Francisco Mime and tying it all back to previous waves of ensemble-based work. Does that all make sense? I'm sort of—

Michael: It does. You can tie it back. And then there's also distinctions I got in a public row with one of the founders of San Francisco Mime Troupe at the 2005 national, at the net conference at Dell'Arte. We got into a bit of an argument because his belief was that political theatre and ensemble theatre concerned with social justice had to be didactic; had to have a single point of view and a message that it was attempting to persuade people to and make change in that vein. And at the time I was there with Witness Our Schools, our public education piece, and I was talking about the importance of dialogue and how I felt that the newer generation of ensemble artists were interested in dialogue more than straight propaganda.

And I said, “I don't believe in 2005, that propaganda changes a single person's mind. And I don't believe you're speaking to anyone other than people who already agree with you. And I don't think that's a particularly good use of my energy,” was what I said. And he was saying that, that was morally relativistic and it was a way out. And we went back and forth a little bit, but I think what we didn't talk about—he and I in that moment—and what since I've thought about a lot, is the context, of course. The context is everything. The time, the place, the world around you.

Between 2016 and 2020, when Donald Trump was president, I would've been hard pressed to say that I thought it was my responsibility to make a space where everybody could be heard equally and given the same proportion of moral weight within the event that I was maybe helping to create, because I felt that disinformation and racism and hate were actually being given a voice and nurtured in a way that was super dangerous to the people all around me and to the potential of this nation, which, of course, that has never reached—this failed experiment based on colonialism and slavery. So I would have that conversation with him differently now, sixteen years later.

So I think the relationship of social justice and civic practice and political theatre to the history of ensemble has a lot of complexities in it. Cornerstone's work and Universes' work also both represent different points in terms of their origin stories and their purpose in relation to the larger theatre field and to audiences. The thing that I was going to say a moment ago was I think that the practice of ensemble is, so far, the great failed journey of the United States. And I think that ensemble theatres attempt to, over and over again, offer microcosmic demonstrations of the potential, sometimes deeply flawed, sometimes really successful, most often both simultaneously.

And that one of the great offerings ensemble practitioners can make, I think, is to find ways in our communities where our experience with the practice of ensemble can help governance and civic life and local decision-making share a rigor and playfulness and curiosity and civility and love and justice that we aim for in our best aspirations as ensemble practitioners. That's what I think our great contribution can be. Probably to me, even more important than what we can contribute to theatre spaces and the theatre ecosystem is that. But that's just my own personal point of view.

Jeffrey: No, and that's what we're here for. Thank you, Michael. Thank you so much for your time and thank you for that sentiment. I really appreciate it. I think I quoted you in my thesis as saying something as such as, “Every ensemble is an opportunity to create a new utopia, a new perfect location.” I remember hearing you say that in class and it's always stuck with me. It continues to resonate with me and be a driving factor. So I want to say thank you so much for taking time and thinking through some of this with me.

Michael: It's my pleasure. Thanks for doing this. I like listening to them, and I'm honored to be a part of it. And I'm glad to get to talk to and see you. Please give my love to Alison and Steven and Mildred. You will have, I imagine, a very playful and funny conversation with them because they are all very, very smart but also very funny people. So give them my love.

Jeffrey: Will do. Thank you again, Michael and we'll talk to you soon.

Michael: Okay. Take care, Jeffrey.

Jeffrey: First, a special thank you to Jerry Stropnicky of Bloomsburg Theatre Ensemble, who is and has been a fantastic thought partner. Thank you, Jerry, for your assistance on preparing for this episode. I probably don't have to say it, but I want to underline how Michael thinks of all of our practices as a means of creating a moral document. How are we meeting our mission with our actions—in our budgets, in our programming? As he says, all those choices represent a manifestation of our purpose. We are indeed in a great moment of recognition and recreation. Ensembles can bring something new to each institution, even their own. Can we make decisions slower or by consensus?

On the next episode of From the Ground Up, we'll be hearing from David Catlin who takes us through Lookingglass Theatre Company’s growth as a favorite Chicago ensemble. He'll carry us through their egalitarian, artistic decision-making process for each season and how it fits their hierarchical administrative model. Also, how the company finds success in touring their works across the country. Thanks for listening artists. And now your soundcheck lightning round.

Can you give me your favorite salutation?

Michael: Probably, “hey.:

Jeffrey: Your favorite explanation?

Michael: I use a strong word sometimes that begins with the letter “f”. This probably escapes my mouth before I can stop myself sometimes unless I'm around the kids, and then I try to do better.

Jeffrey: Right on. Your favorite mode of transportation?

Michael: I really like to drive. I'm very happy driving. Yeah.

Jeffrey: Your favorite kind of ice cream?

Michael: Häagen-Dazs, cherry vanilla.

Jeffrey: And then what would you be doing if not theatre?

Michael: I spend a lot of energy at the intersection of community development and government and change. So I would probably be more and more fully in that world.

Jeffrey: And what's the opposite of CPCP?

Michael: I'm part of a collective. I'd be so interested to know what everybody's answer would be. For me, maybe the opposite would be an extremely hierarchical corporate setting that had a bottom line of financial profit only as its key priority.

Jeffrey: This has been another episode of From the Ground Up. The audio bed was created by Kiran Vedula. You can find him on SoundCloud, Bandcamp and flutesatdawn.org. This podcast is produced as a contribution to HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of this series and other HowlRound podcasts in our feed on iTunes, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and wherever you find your podcasts. Be sure to search HowlRound Theatre Commons podcasts, and subscribe to receive new episodes.

If you love this podcast, post a rating and write a review on those platforms. This helps other people find us. You can also find a transcript for this episode, along with a lot of other progressive and disruptive content on howlround.com. Have an idea for an exciting podcast, essay, or TV event the theatre community needs to hear? Visit howlround.com and submit your ideas to the commons.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here