Stereotypes in Traditional Mask Designs

As a mask maker, I am tasked with representing a character on stage. I'm often asked to fabricate masks for training, rather than a particular character. The goal is to convey strong aspects of character for anyone wearing the mask. This is tricky because there are no genetically impartial features; our physical bodies all have connections to our unique heritage. When tasked with representing social status in a mask (as is required in CdA masks), you must answer impossible questions: “What does a lower class nose look like?” “What features should signify ‘poor’?” This is the mask maker’s conundrum.

It took years for me to realize that it is my responsibility to represent students of today, not players of the past.

In the US in 2023, anyone is supposed to be able to attain wealth. This was not the case when Commedia dell’arte was a dominant theatre form, and is not reflected in Renaissance-era masks. Of course, opportunities for people of color and marginalized identities to attain wealth today are drastically less than those of dominant cultural identities. But theatre is aspirational—it should serve everyone and reflect today’s diverse world of players.

As a mask maker, my first instinct was to mimic the ideas and designs of my predecessors. It took years for me to realize that it is my responsibility to represent students of today, not players of the past. To do so, I have made many changes to this traditional form.

Separating the Harm from Commedia Characters and Their Masks

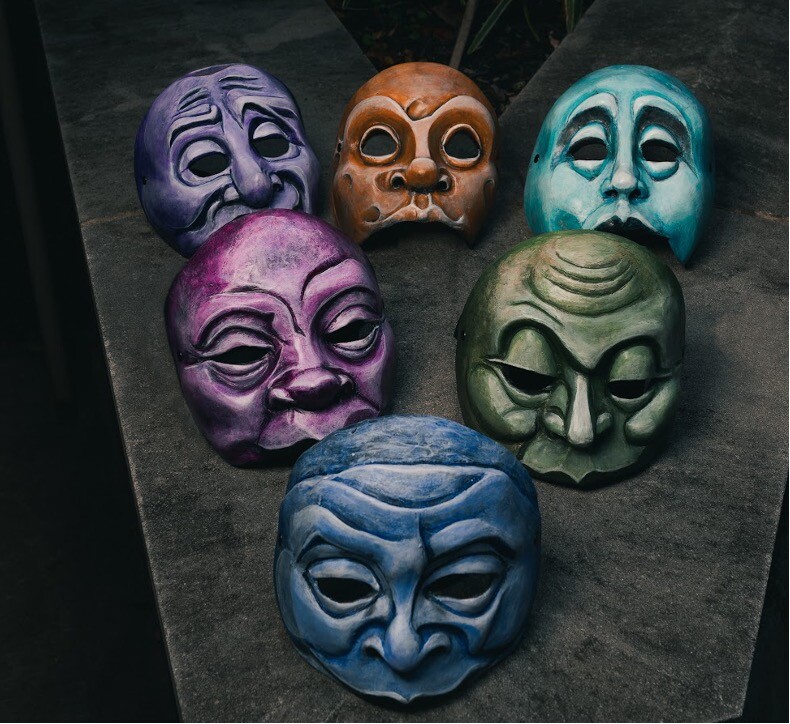

When I began, I had to identify the most important parts of the Commedia acting experience for students. I didn’t want to do harm. Traditional Commedia dell’arte masks have rich histories, but also deeply embedded stereotypical features that stem from ageism, racism, sexism and misogyny, genderism, classism, ableism, etc. I refused to put that pain into the masks that I would use to teach Commedia. But how? If I didn’t use the “stock” characteristics of Commedia’s traditional characters, would people know who they were? And given the harm that has come from contemporary artists using these masks, should I make new masks that are recognizable as the traditional characters they stem from, or should I abandon those models altogether for contemporary devising practice?

I had been using emotion play with Commedia students for fifteen years, so I knew I would be building emotions into the new masks. Emotions play across a face bombastically, throwing symmetry out the door in favor of fascinating visual events—a crinkly nose lifts one side of a lip, pulling the entire left side of a face upwards in wrinkles. Emotions create intersections, conflicts, and big changes of direction: everything the Lecoq territory on Commedia dell’arte might highlight as the purpose of the play.

Emotions are archetypal—recognizable in a large majority of humans across experience and history. Archetypal qualities differ from stereotypical qualities; archetypes are driven from within an individual, whereas stereotypes are driven from external identification. This was the foundation for my pedagogy, “Embodying Archetypes.” I reasoned that if emotions are not generally part of the mask shape for traditional masks, but I knew they lived in those stock characters, I could use those shapes to give definition to new masks.

There were other “archetype containers” I considered for building meaning into the Reimagined Commedia designs, several of which I used, including: inspiration from Carl Jung and his archetypes, the Rasas from traditional Indian dance, family member archetypes, the Grand Passions (a list of character qualities included in my training at Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theatre), elements from nature, and the traditional hierarchical form from Commedia and European clowning. These collections of archetypes gave definition to an idea that might be used in a physical way when sculpting a mask or embodied by an actor: I was looking for archetypes that could do both.

Partners

My concept was to reimagine the way Commedia could play in the Lecoq-informed traditions with archetypes rather than stereotypes, with masks that didn’t hold a history of harms embedded in their features, and with values that redefined the energetic focus of Commedia-inspired play by centering justice and joy. I needed collaborators who could also see what I saw. I was actively seeking environments to develop these ideas into practices. It wasn’t until I was approached by Faction of Fools Theatre Company that the work began to flourish.

I am blessed to partner with people who are passionate about this work: Francesca Chilcote and Kathryn Zoerb, the co-artistic directors of Faction of Fools. We spent many hours sharing concerns, observations, and interest in finding articulation of specific traditional stock characters for new, less harmful masks. They hired me to sculpt the masks using a rubric of archetypal qualities inspired by the traditional masked characters. We worked together to think about how these concepts would inform the company’s foundational training, “Commedia 101.”

Developing the masks and training side-by-side, I continued to bind mask functionality with social justice directives. Faction of Fools funded and co-created the reimagined masks, and became my partners in discovering how these parts would converge to make new, Commedia-inspired actor training.

Abandoning Traditional “Hungers”

Aiming for masks that were true to the work we loved, we first identified qualities that we did not want to see in the reimagined masks. We referenced the traditional wants and needs of the historical characters, the “hungers” of the three societal classes presented in historical Commedia. Generally, when CdA characters are taught, they are given a class-specific directive like, “The servant class wants to eat. That is their behavioral motivation.” I recognized how classist it is for today’s actors to categorize an entire class of people as “servants,” and to say, “all that class wants out of life is to eat.” This line of thinking denies human complexity, and makes stereotypes of everyone. However, by removing singular wants, I removed a lot of what practitioners found so advantageous to the form: its ability to quickly facilitate embodiment and movement stemming from those wants. It is this freedom to play in a well outlined container that makes Commedia so fun. I needed to keep a central want for each character, but one that didn’t encourage stereotyping.

Eliminating the articulation of “a class of person with specific class-wants” loosened the chokehold of stereotyping on the form. When we drop the connection between character social class and character hunger, we acknowledge that our human identities have definition beyond our status within capitalism.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Yes yes yes! What a great article to start my day! I'm constantly looking for the "Fast Food Worker" dell'arte clown, the "Air Traffic Controller" clown, or the "Eccentric Cat-Person" clown in my classes rather than the traditional. What amazing context and content! And thank you for tying in Lecoq to this. I'll be sharing this next semester promptly!

Thrilled to get to share it, Jeffrey! Thanks for your enthusiasm! Don't hesitate to reach out if you want to connect further!