Transcript of a podcast featuring Cannupa Hanska Luger

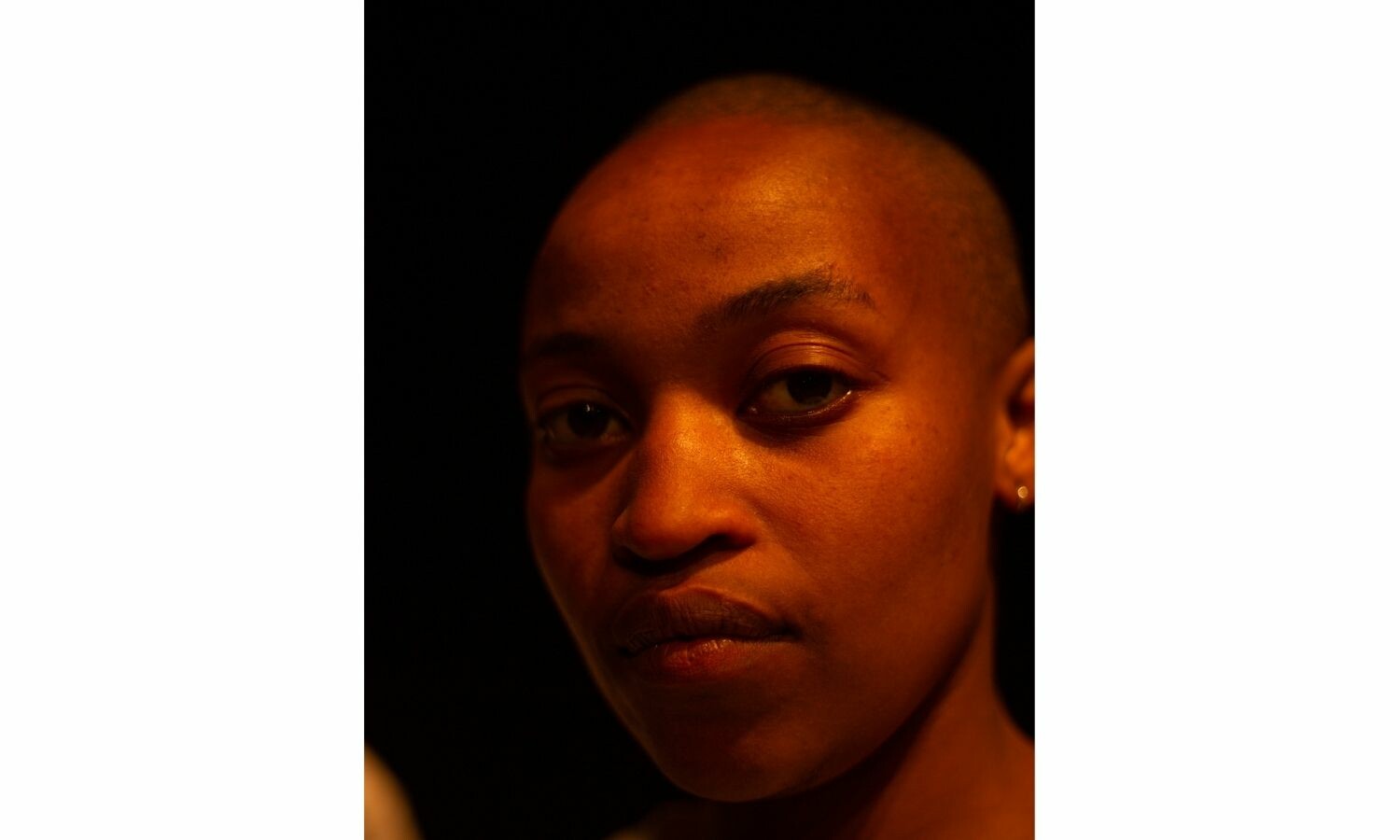

Simon Dove: Hello, and welcome to The Future Is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink. My name is Simon Dove. I'm the executive director of CEC ArtsLink. For this podcast series, we asked ten independent artists and curators from different parts of the world, whom we call the Future Fellows, to talk about the current context of their work and to share their vision for how they see the future of arts practice. In this episode, we hear from Cannupa Hanska Luger, based in Santa Fe, U.S.A.

Cannupa Hanska Luger: I'm Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara, enrolled member of the three affiliated tribes (of Fort Berthold), from Dripping Earth Clan. I have a background in ceramics but do a lot of mixed media and installation using digital media, and basically any material that I have access to.

Models that we've used for the celebration and ultimately the commodification of art are being questioned today, maybe amplified through access to social media and communication. This sort of platform actually undermines the whole preservation model that most institutional spaces have been relying on for a few centuries. Our capacity to utilize the digital sphere opens up and challenges the way that art is related to. Art and culture are verbs; active and alive, in flux and changing.

As an Indigenous person in the United States, I recognize that deep-time historical relationship to making your life beautiful; art is a by-product of that. These are living examples of our culture and creative process. So, as we move forward in time and have a much broader reach communicating with one another across what were initially geopolitical borders, conversations from a multitude of cultures that have been silenced or ignored throughout the last couple of hundred years are actually communicating with one another and bypassing the center for culture share, which would be your museum or gallery or market, even, of information.

With access to that amount of communication, technology, and inspiration, we can actively participate in the maintenance and adaptation of our own cultures through ideas drawn from the lands of each indigenous community across the globe. My own practice, having a background in ceramics, there is an emphasis on this historical object that can exist in defiance of entropy for a long time. So I wrestle with the idea: Am I making these objects, or are the objects actually making me?

Going from three-dimensional, hard ceramic forms is informing me on how to create more performative acts, which exist in the fourth dimension, with time. Film and digital media allow me to create a record of those experiences that can then be shared on a global network versus my immediate community. All of that is in response to this umbrella of consumerist capitalist influence that also breeds voyeurism and narcissism. How do you subvert these two very toxic traits? Using social media as a platform for people to participate in the creation of work, and/or celebrating and sharing work that emphasizes an alternative way to engage with your environment, to see your land with reverence rather than just resource.

I believe from my own experience, how you amplify and lift each other up in certain ways have existed for a long time; that there are grassroots models of how to organize, to communicate. You see a lot of artists and artwork and culture bearers existing on the same platforms as say a resistance or protest narrative. But that is the same kind of functioning model that generates a potential alliance and intersection of peoples' varied experiences. They become a tightly woven network of communication, ask, and support. So tightly woven, it's harder to fall through that network once you're part of it, whereas the larger industrial, colonial, empirical model is a loosely woven network, and many people fall through.

A grassroots effort to do so actually generates more of a connection to your immediate community. And that, as a model to participate in, also influences the way you interact with your immediate family, roles in the household. Then beyond that, within the neighborhood, community, environment, there's a reverberating network of care, a model that had worked for tens of thousands of years and was deemed primitive at some point in history. But we are quickly recognizing that it is a more holistic way to engage with community that's not a code word for Brown and Black people.

The effort to dismantle existing institutional spaces may be wasted because they are brick and mortar. We'll never understand what a decolonial experience is because their core existence is the transformation and the annexing of land and space. So these spaces, I don't know if they can ever become truly a decolonial experience. However, the effort to decolonize feels like important work. But I'm more interested in how we re-indigenize our way of thinking that has a root in its relationship to space and land, and consider that the creation of something else is the best way to destroy something that's obsolete. I'm no longer in a demolition process but rather can help to generate something that will make it obsolete.

That's what I'm hoping to see but also don't have any expectation of experiencing that in my immediate lifetime. We are sowing seeds. The fruit is for future generations. I may never live in the world that I imagine, but I am happy to die trying to create it. And the notion of that sort of effort, of pushing this envelope slowly forward, is encouraging enough for me to continue.

There is no effort made now that isn't going to be worth something a generation from now. And I'm happy that there is a level of disorganization in this learning curve process that develops a much cleaner communal idea of what the future is going to look like—especially when we're dealing with institutional practices based on order. I don't think you can use order to dismantle that.

The chaos of trying to understand and trying many different modes to dismantle and/or build and establish a new paradigm are equally valid. I'm happy that I can work in my own independent way and understand that I'm not alone in that effort, that there are many, from many different angles, coming in and converging on what we want as representation of not only ourselves, but our community and how we want to share culture and art with one another.

Whatever I'm doing is not necessarily sustainable. It's in response to the environment that I live in, but as all of that starts to shift and change, I have no idea where my next structural support system will come from, and I don't think it will be from the one that I'm developing presently. It'll be some other underlying network, whether that's a farmer's union, an imprisoned population, a homeless community.

I don't know which one will end up being the most beneficial, but I'm happy to apply a variety of ideas and know that others are applying a variety of ideas, and that down the road one will be praised and the other will be abolished, and whatever survives that crucible will be what we end up kind of utilizing. What works for one region doesn't necessarily work for another, so I would be interested in the multiplicity of possibilities rather than trying to find a unified theory for us.

Because I cannot exist in the future that I imagined, I have been of late obsessively developing work that is indigenous futurism, science fiction, ideas and forms emphasizing ancestral knowledge, applying it through new material and imagining what a potential culture and community could look like.

I can imagine, and have even seen, life growing in Superfund sites and areas decimated through extractive industry and pollution, and somehow, some way, I could make a go at it here. Let's look at our more-than-human kinships; our relationships to our environment and space. Then instead of looking at it as a potential resource, let's look at it with reverence and understand that there is an important wealth of knowledge that a blade of grass growing through a crack in the concrete can share with you if you look at it in the right light and perspective. You realize what we call urban spaces is a front line trying to annihilate life as it's continuously dismantling the infrastructures we've created, breaking it down and turning it into a spring for growth.

I see it in our most polluted areas, our most economically despaired areas, and in our wealthiest areas as well. It finds a way to generate growth. And what I tried to do with my work, what I'm interested in is, how do you unshackle this notion of humans versus nature? How do you reestablish a kinship and a relationship to your own environment so that you see yourself as an extension of it, rather than something separate?

As we talk about environmental efforts and things like that, we need to be real honest about what we're talking about: that the ship is going to keep moving, the planet will keep revolving. It was happy a ball of flame, it was happy covered in ocean water. As a highly adaptable species, why have we forced nature to adapt to us when we can adapt to just about any climate? Every diverse culture you've seen in history books and museums and everything, every phenotype, all were developed out of adaptation to place.

My optimism is based on what I have seen as a living thing on this planet. I get to share one of the most complex, complicated, incredible powers and forces at play, and somehow just by being brought into this space, I am a participant. I have a direct line to the sun we circle, the moon that affects our tides. There are so many forces at play, but they are not against you if you understand you are a part of it.

We're not guaranteeing ease. Difficultness is what makes us better at living. Challenge is what hardens our body and hones our senses. My optimism comes of sheer awe of being anything at all. I'm also a father. What would I do with pessimism or defeatism raising two young boys? I'm only borrowing this place from them. We are only borrowing our world and our life and our experience from future generations. It's about time we start acting accordingly. Dramatic pause.

I have a hard time placing myself in the position as artist. Primarily our function in society is social engineering. We build bridges from our perspective to another, and it's not necessarily that we ask people to trust the construction of that bridge, but that its creation allows them the possibility of crossing, wayfinding, and pathfinding.

Linking artists together is incredibly important and is also what naturally happens to the creation of any sort of object or work. Not only can you communicate with living peers, but you can communicate with the dead and unborn. That's what we try to do, we are talking.

This social engineering is an impossible architecture because it has the capacity to span time and space. Any interaction that allows us to communicate with our present peers, also those geographical, social, and economic experiences, become pillars of bridge building. I can span the gap if I know where it's going to land, and working with artists from other regions and communities allows you to understand where your span is going to reach. Possibly we're both building in the same direction.

It's important to retain some sort of understanding and relationship to the place that you belong to and the land that you belong to and build these paths and bridges for those who want to push the edge of that. And somewhere along that span, people may build a whole culture and civilization that will span in another direction.

And it's their responsibility, their artists, their culture, that will then generate an even tighter network of communication, so I don't think we do build them necessarily for us. We can cross them, we can go and meet, but that's not why they're built. They're built for the public, for the community, the people at large, who aren't necessarily doing that sort of thing, but it creates a platform for people to meet somewhere along that path. I'm just building bridges, man.

Simon: You have been listening to The Future Is Now, a podcast series from CEC ArtsLink with support from HowlRound. All interviews and postproduction is by me, Simon Dove, executive director of CEC ArtsLink. The specially composed music is by the extraordinary bass player and composer, Shri. This podcast is part of the ArtsLink Assembly 2021: Future Fellows, supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, Kirby Family Foundation, John and Jody Arnhold Foundation, and of course, generous individual donors. These podcasts are available to listen to, or download the transcripts at our website, www.cecartslink.org, or at howlround.com.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here