Gender Euphoria, Episode 4: Training Cisgender Producers and Directors: It’s More than Remembering Pronouns

With Maybe Burke

Nicolas Shannon Savard: Hello, and welcome to Gender Euphoria, the podcast, supported by HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. I’m your host, Nicolas Shannon Savard. My pronouns are they, them, and theirs. For today’s episode, I had the chance to chat with actor, advocate, solo performer Maybe Burke about her role at the Transgender Training Institute.

The discussion really beautifully blends the deeply personal and broadly systemic. We talk about big questions about inclusion, and access from college theater programs, to primetime TV sets, the inextricable links between performance and activism for trans artists, and of course her seminar she facilitates, titled Supporting Transgender Actors and Creatives.

To give a brief introduction, Maybe Burke is a New York-based actor, writer, and human rights advocate interested in telling stories that haven’t been told. Their work has been seen at Joe’s Pub, Lincoln Center, Cherry Lane Theater, Arts Nova, New Dramatists, Here Art Center, The New York City LGBTQ Center, and more.

Maybe has spoken on many panels and facilitated several workshops around trans and queer identities. They have spoken all over, from Broadway Con, to Buzzfeed, to universities. Maybe is a queer educator and core trainer with the Transgender Training Institute, which we will be diving into more in depth today. You can read Maybe’s full bio in the show notes.

Rebecca Kling: Gender euphoria is...

Dillon Yruegas: Bliss.

Siri Gurudev: Freedom to experience—

Dillon: Yeah, bliss.

Siri: masculinity, femininity, and everything in between—

Azure D. Osborne-Lee: Getting to show up—

Siri: without any other thought than my own pleasure.

Azure: as my full self.

Rebecca: Gender euphoria is opening the door to your body and being home.

Dillon: Mmm. Unabashed bliss.

Joshua Bastian Cole: You can feel it. You can feel the relief.

Azure: Feel safe.

Cole: And the sense of validation—

Azure: Celebrated

Cole: —or actualization.

Azure: Or sometimes it means

Rebecca: being confident in who you are.

Azure: But also, to see yourself reflected back.

Rebecca: Or maybe not but being excited to find out.

Nicolas Shannon Savard: Hello and welcome back to Gender Euphoria, the podcast. I am here with artist, actor, performer, educator activist, Maybe Burke. Today, we’re going to be talking a bit about building a more trans-inclusive theatre and a bit about Maybe’s role at the Transgender Training Institute and their intensive workshop, specifically for cisgender producers, directors, other artistic leaders looking to create more gender inclusive educational spaces, rehearsal rooms, theatrical venues. Basically, how do we create inclusive spaces and practices around us in the theatre? Maybe, could you tell us a little bit about what is the Transgender Training Institute, and how did you come to create this particular training for the performing arts specifically?

Maybe Burke: Yeah, definitely. The Transgender Training Institute, we’re a trans-run organization that provides trainings facilitated by trans and non-binary educators. We have a goal of contributing to a more just, equitable, and affirming world. Everything we do is just for the people and by the people. We’re doing all kinds of content and workshops, webinars, courses for making sure people have the tools that they need to make spaces more inclusive and comfortable for the trans and non-binary people in their lives.

Nicolas: That’s beautiful. Can you tell us a little bit about how you ended up creating this? I read on the website ten-hour class specifically for creating these kinds of inclusive spaces for trans and non-binary actors.

Maybe: Yeah. It’s 10 hours overall. It’s not 10 hours straight.

Nicolas: Yes, I figured that. That would be a long time. When I say ten-hour courses, people are like, what?

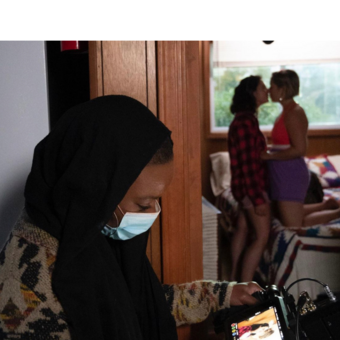

Maybe: When I started working with TTI, we had a program called An Ally/Advocate Training Camp, where we were teaching people how to be allies and just building that toolbox for folks. We started getting a number of theatre and TV people showing up to those things. Then when the pandemic hit, we moved everything online and started doing virtual offerings. Eli Green, our founder, called me and was like, “Do you want to do a course just for your theatre people?” I was like, “Yes, I do.” That was the genesis of this course because we had a bunch of intimacy directors specifically, but a lot of producers and indie directors and folks showing up, wanting to have more specific conversations to the industry and to our field.

I was like, “Let’s just do it then.” Now we get to dive into conversations about representation. We get to dive into the meat of casting issues, and how we deal with transactors and creatives on set. We get to talk about what we do when somebody messes up or addressing microaggressions, but in specific contexts, it’s not as general as just learning to be an ally. It’s learning to be a colleague. It’s learning to work within our field, and within our structures, and have these conversations.

Nicolas: Great. It doesn’t surprise me that kind of intimacy choreographers, intimacy directors, were kind of at the forefront of making this connection here. I had not thought of that before, but this makes a lot of sense to me. Can you talk a little bit about what those initial conversations looked like and what the overlap is between that sort of intimacy work, and creating inclusive spaces for trans and non-binary folks?

Maybe: Yeah, I experienced it firsthand because I worked on a TV show, and I learned what intimacy directors do because I met one. I was cast in a show where I knew I was auditioning to play a man or the role was written for a man. When I auditioned, the role’s name was just “Patient.” Then when I booked the role, they changed it to “Gay Man.” My managers were like, “Ooh, let’s not have that on your IMDB page.” They were like, “We'll have conversations with casting and see if they can change it back.”

Then the next day, or later that week, the intimacy director on the show called me, Alicia Rodis, who is also one of the top-notch intimacy directors in the field. She was like, “Hey. I heard there was like some uncomfortable gender stuff going on. I’m the intimacy director for the network. Do you need anything? Do you want me to come hang out on set and make sure you don’t get misgendered?”

I was like, “Who are you? What is your job?” I was like, “That’s an option? How do I get your job?” She was just free that day and was like, “What do you need?” To which I was kind of like, “Have you Googled me? I think I’ll be okay.” I was actually already emotionally prepared to get misgendered a ton because I knew what role I had auditioned for, and I was comfortable telling that story. It was like a one-liner. I ended up being written off the show. The show doesn’t even… I’m not in it at all, but that started our conversation. She ended up coming to one of our ally training camps when they were held in person.

That spearheaded this whole shift into a lot more people. She was recommending people to come to this. It’s part of intimacy director is getting certified. They can take my course to be part of their certification and all of these things that... Intimacy directors’ jobs essentially are to make sure that actors and everyone in the room is comfortable and feeling safe when we’re addressing intimacy, when we are dealing with intimate scenes and material.

Part of that is making sure everybody’s gender is being affirmed. Part of that is making sure that everyone feels safe and welcome and respected throughout every part of the day. Whether or not we’re doing a sex scene, intimacy means a lot more than that to me. Intimacy, to me, it’s very intimate for me to walk on a set and be the only non-binary person there, and not know if people are going to get my pronouns right. That’s a version of intimacy for me. It makes sense to me that intimacy directors would play that double game.

Nicolas: They’re really dealing with the power dynamics and emotional kind of landscape of everything.

Maybe: Yeah. That’s a thing that we talk about a lot when I’m working with intimacy directors is power dynamics. You correcting somebody who misgenders me is going to land a lot different than me, this actor who was hired for a co-star and is on set for one day, trying to get people to use the right pronouns for me.

Nicolas: All of that makes me so happy.

Maybe: I know, right?

Nicolas: It makes me so happy.

Maybe: Like, “You do this? Okay.” She checked in with me about how I wanted it done. She wasn’t like, “Oh, a non-binary person is coming. We have to do this, this, this, and this.” She was like, “Hey, how do you want this handled? What do you need in this?”

Nicolas: Yeah. Really putting the agency back in your hands.

Maybe: Yeah, like handing me a sliver of her power.

Nicolas: Yeah. Amazing. Amazing.

Maybe: Also, shout out to Alicia. I just love her and think she’s doing...

Nicolas: Yes. Fantastic. I know that this role with the Transgender Training Institute is not your only advocacy slash educator role. I’m sure some of these ideas come through in your solo performance, in your general career as an actor and a performer. I’m curious, for you, what's the relationship between your work as an actor and an artist and your work as an activist? How do those roles, if they even can be entirely separated for you, how do they influence one another?

Maybe: Yeah. The idea of entertainment existing just as entertainment is one of the funniest things I’ve ever heard. Theatre has such a political history and lineage, and the ways that so many stories that we’ve told, movies that we’ve watched and all of those things, have deeply rooted political and social justice themes. Literally superhero movies. Star Wars going against the embassy—I don’t really know Star Wars, but the bad guys.

Nicolas: Yeah.

Maybe: A lot of those things are aggressively anti-establishment, right?

Nicolas: The empire, I think.

Maybe: The empire. The embassy, who am I? I’m stuck in political dramas. When I started, I started doing musicals in the fourth grade. I didn’t know what I was doing in terms of social justice. I didn’t actually want to pursue theatre. I wasn’t going to school for it originally. Then I realized it was kind of all I cared about, so I did go. Around the same time that I transferred schools and started pursuing theatre, I also was discovering that I’m trans and discovering that there’s not a lot of space for me in theatres. There’s not a lot of room there.

Inherently, me walking on a stage these days is going to be a political act. I can’t be an actor without it being politicized because of my identity. That’s not an option for me. Also, when I started realizing that there weren’t spaces for me in at least mainstream theatres, I made a blame of artistry for myself that was going to be heavily political and steeped in advocacy. I did a solo show about my love and sex life that is inherently political because I had colleagues who were trans and non-binary saying things to me after the show, like, “That was the first time I've seen a trans feminine person on stage who loves themself.”

There were stories that I was telling that had never been seen by people before because not enough people like me get to tell their own stories. I didn’t actually start pursuing mainstream commercial gigs until like 2018. I was working downtown, doing the kind of stuff that I like and I know how to do. Then I was trying to figure out how I make a career. How I have longevity and can sustain myself. I really wanted to focus on advocacy work because I think I’m very good at getting people to move from like, “Okay, how do I use the right pronouns?” to being like, “How do we dismantle capitalism?”

Nicolas: Yes. How do we entirely restructure our industry?

Maybe: Right. When I started pursuing TV and Broadway, I was doing so to get a stronger platform for my advocacy. Me being an actor is directly linked to my advocacy work and is… Yeah, one can’t exist without the other. My advocacy can work without me being an actor, but a lot of my advocacy is told through storytelling. At the end of the day, it’s all emotional storytelling that I use to meet people where they’re at, to find people ins to caring about these topics. It’s all part of my acting and my writing.

That background is definitely embedded in my advocacy work, and who I am as an artist is deeply embedded in advocacy. I’m in rehearsals with folks and I'm going to interrupt people. If they say something harmful. I’m going to be one of the first people to speak up and stop situations I’m uncomfortable with. I’m also going to push back on writers if I think there’s a harmful trope in a script, and I think it could be told in a more responsible way. I’m not going to let myself be part of a story I don’t believe in.

For me… I mean, this course that I teach is the intersection of everything I ever wanted to do with my life. I literally am so grateful every time I get a room full of people who want to be part of that conversation with me because neither of my two lanes can exist without the other. If I wasn’t an actor, my advocacy would look so different and probably be far less effective because I wouldn't have the same toolboxes that I have.

If I wasn’t an advocate for myself, I wouldn’t get into most rooms. If I wasn’t able to write a story of my own, I wouldn’t have gotten a name in that downtown New York scene that then made me get a manager. That then made me get seen by people, so that I could move into pursuing more mainstream work.

Nicolas: Yeah.

Maybe: It’s exhausting.

Nicolas: Yes.

Maybe Burke: I’m so tired. That’s the funny thing of it. I talk about wanting to tell these stories more responsibly and everything, but in reality, what I want is to book a series regular on TV that wasn’t intended to be a trans role. I want to just play someone’s best friend, like girl-next-door kind of neighbor and not actually have to talk about. That’s my ideal is just…I don't want to tell the trans story.

Nicolas: Yeah. I think what you're talking about, this relationship between advocacy in your artistic work and as an actor, resonates with so many of the things that I’ve heard from other people.

Maybe: Yeah.

Nicolas: No matter which direction they came at it with, and it’s just really skillfully using those stories that get people to connect with you, as just another person.

Maybe: That’s what’s our job as actors. That’s how we do that. Okay. I played Angel in Rent in high school. I’m Irish. I should not be playing Angel. Sorry, but that role—

Nicolas: Somebody cast you.

Maybe: It was Long Island; we had an almost all-white cast. Whew. I learned a lot about how to manipulate an audience with that role. I learned a lot about myself, obviously, getting that as well, but the reason Angel’s death was so impactful on audiences is because she’s the heart of the show. She’s the sweetheart, and everybody loves her. She’s funny, and she’s witty. And she’s a fashion icon. You make people fall in love with her so that when she’s taken from us, it is devastating. That’s what I’ve realized we have to do in advocacy work. We have to make people care about the thing so that they realize how much harm it’s contributing to the world. We have to realize… We have to make people care about trans people before they can care about speaking up for trans people.

Nicolas: We’ve got to make people care about us as entire humans and not just an abstract idea.

Maybe: Exactly. That's why I do tell my own stories, so people remember I’m a human and not just this mouthpiece that’s talking to them right now. When I talk about privilege that I hold—because I do have a lot of different privileges that I hold—I do list being cute as one of those privileges because I weaponize my cuteness to make people like me. If I’m the first trans or non-binary person that a participant in one of my webinars has ever seen, or actually listened to for a long period of time, I need them to like us. I’m going to be cute and funny and palatable, so that their first interaction goes well.

Nicolas: I do that all the time in my teaching. I teach a bunch of gen-ed theatre classes. Many a student has told me that I am the first trans person they’ve knowingly met. I am the first non-binary person they’ve knowingly met. I open with like, “Quick grammar lesson, in case you forgot what pronouns were. I’m going to use examples that are kind of funny.”

Maybe: Yeah. We make it less scary that way.

Nicolas: Make you like me, so that when I get to later in the semester and put myself into these big political conversations that we’re having about The Laramie Project or whatever, like, “Okay, so I can tell you about these laws and things. Here’s what this means for me and my wife.”

Maybe: Right. You’re going to care—

Nicolas: Here’s what’s going to happen.

Maybe: —because you know somebody who’s close to it.

Nicolas: You’ve spent nine or 10 weeks being in class with me twice a week now.

Maybe: Right. You care about me to a degree, hopefully.

Nicolas: As much as you do your instructor.

Maybe: Right, but that is a thing. If you like me a little bit, you’re going to care more about things that are going to directly impact my life. Yeah. I reference Angel quite often, actually, because she’s a prime example of we are going to make the audience fall in love with this, whether we’re calling Angel trans or gender nonconforming, however we’re categorizing her. We’re going to make people fall in love with her, so that we get the emotional response when she’s taken from us. That’s, I think, the crux of good storytelling.

Nicolas: Yeah.

Maybe: I have a friend who refers to a lot of my storytelling as emotional whiplash, and where I’ll be really cute and fun. Then you realize it’s about trauma and it’s like, oh, okay. It makes you care about it, because you’re laughing. I think that channel works really well with advocacy where we’re going to be like, “Here’s what we’re talking about. Here’s the sunshine and rainbows of it. Here’s what we need to do in order to fix the problems. These are the problems.”

It’s funny because when I started building this course and talking about these things, our founder, Eli was helping me talk about it. I was like, “I don’t have a background in education. I can’t build a curriculum or anything.” He was like, “You’re a storyteller. You can do this. You know how to move people through what they need to move through and get people to where they need to be in the learning process.” He was like, “You know how to do this—”

Nicolas: You know how to introduce information gradually so that people catch on.

Maybe: Yeah. He was like, “Do it. We’ll talk about it and fix it if it’s not good, but do it.” He was like, “You can do it.” And I could.

Nicolas: Back to the course itself, what does it look like in practice? What’s the setup?

Maybe: Yeah, so day one kind of goes through setting the stage and basics. We do a chunk of basically trans 101, just to make sure we’re all operating with the same language, and we understand how it goes. But also diving deeper and being like, “This is what it means in your characters. This is what it means in our storytelling where we dive a little deeper in there.” Then day two is a lot about implementing it and practicing. Day two is us doing role plays of somebody said something icky in rehearsal, and you need to step in and fix it because the trans person doesn’t want to, and they’ve asked you to step up.

We also watch a video. My dear colleague and friend, Lynn Marie Rosenberg, has a TV show now that used to be a YouTube series, that used to be a live show at Joe's Pub, that used to be a Tumblr page where she—

Nicolas: What an evolution.

Maybe: Right. It’s wonderful. She basically collects bad breakdowns, and terrible offensive breakdowns for any type of person for any demographic. The TV show now with all arts is called Famous Cast Words, but we watch clips from when it was Cast and Loose Living Room where I made kind of a super cut with her permission. She let me use her videos of all of the really scary, bad trans breakdowns that she's come across. We watched those to kind of start getting the wheels turning of like, “What are trans and non-binary folks seeing when they’re trying to get a job? Why are they maybe not showing up to some of these auditions?” But also, “How many microaggressions do we have to face before we've even met anyone on set? Before we even got into a rehearsal room?”

A lot of what I’m doing is actually not so much teaching people how to deal with the problems but making sure they know what the problems are. A lot of the foundation has to be like, “Sure, we can say we’re going to support trans and non-binary folks, but if you don’t understand what’s going wrong, you can’t help to make it right. You can’t be part of that push until you really see what we’re going through.” Throughout the 2 days, the 10 hours, I also share my own horror stories. I talk about meeting Alicia and that story is also a part of it and learning that that exists and the positives, but I talk about the director who asked me my pronouns and then never used them on set. The amount of people who have brought me in for an audition for something that I couldn’t do, but they thought they were being inclusive, so they thought it was cool.

All of those pieces, I specifically only tell my own stories during those things, because I want them to realize how much this one person has had to go to through in what I think of as a pretty short-lived career, and that these things are constant and they’re everywhere. Whether or not your set is going to be full of microaggressions, folks are still going to be on edge, just being afraid that something might happen. It’s very hard to trust a new space when you've constantly entered new spaces that aren’t affirming.

Nicolas: Yeah.

Maybe: I’m so sorry for whatever I just made you think about.

Nicolas: That’s okay. That’s okay. I think that’s really just underlining what even are the problems or barriers that we are facing. It’s like… It’s not about pronouns. It is—

Maybe: so much deeper though.

Nicolas: That’s layer one.

Maybe: Right. This is the part you hear. Pronouns are like a red flag that there’s going to be worse. There’s going to be more.

Nicolas: Yeah. It’s not about the bathrooms. It is, but it’s not.

Maybe: Right. Exactly. A lot of people come into class knowing the like, okay, so dressing rooms are an issue for non-binary folks and pronouns are a thing for folks. They know the hit points, but then after the first day they’re like, “Oh, those are the things that get talked about in the news. That’s not the thing.” There’s so much more underlying, and there’s so many other pieces that we’re not thinking about it. We’re not realizing, we’re not recognizing what the tropes are. Trans and non-binary folks are. We’re aware of the tropes we’re getting asked to play over and over again, but also what is the impact on a person when they’re asked to play those tropes? What are we doing to people when we’re hiring them to get misgendered all day?

Nicolas: Then the public persona that they get to put out into the world is this trope.

Maybe: Right. I’ve been in shows where I was hired to get misgendered over and over again. I’m like, “Okay.” Depending on if it was like theatre or TV, like hundreds or thousands of people are just seeing me get misgendered over and over again now. What are you doing to me? Okay, that’s just out there now.

Nicolas: Cool. That’s out there now. What are you going to do with that?

Maybe: Right? Are we learning from it?

Nicolas: Yes, this happens. Now what?

Maybe: Right. How we address it is important. Yeah.

Nicolas: Yeah. What are some of the most common questions or concerns that directors, producers, intimacy choreographers, teachers are bringing into these trainings—knowing that obviously we are not going to answer all of these questions right now, but what are some of the things that folks are coming in with the most often? For the answers and those full-on discussions, they can pay to take the training.

Maybe: Right.

Nicolas: There’s your ad right there.

Maybe: Thank you so much. I think it depends on what positions you hold. What your questions are going to be. I find most of the people who take the course are multihyphenates. It’s very rare that I get a person who’s a director and just a director. Intimacy directors, usually their most burning question that they have going in is, “What do we do about intimacy garments? How do we deal with modesty garments?” Directors are usually just worried about the rehearsal space and how to make the space welcoming and affirming. Writers are there being like, “How do I make trans folks feel comfortable auditioning for my things? How do I write a breakdown? How do I make sure I’m not leaning into those tropes? How do I tell a responsible story?”

Then there’s a mixed bag across the board of just like, “Is they okay for a singular person?” There’s all the typical questions that come with it. For the most part, yeah. It’s specific questions about intimacy and how we have language around body parts for characters and/or actors in those scenarios, similar to conversations around costuming and getting certain garments for folks. Or it’s just like, “How do we make sure our space is as welcoming as possible? Then how do we tell responsible stories?” Which is the crux of why I built, those questions are answered whether or not they come up for folks, because they’re in the curriculum.

Nicolas: Of course. What are some of the bigger questions that folks are asking by the end? After they’ve gotten past their initial, “Why did I come here to learn these questions versus what am I asking on end of day two, day three?”

Maybe: Right. That’s with almost everything that I do with TTI specifically, we like to say, “You probably came here with a lot of questions, and you’re probably going to leave with more. But hopefully you’ll also have more tools to help navigate those conversations.”

Yeah, I find that people come in thinking about this specific thing, or they have their short list of questions, but then they leave being like, “Okay, how do we make an entire industry shift where we actually knock out the people in power and make sure we are prioritizing the voices of trans and non-binary folks?” It goes from like, “How do I make sure this person that we hired feels safe and welcome?” to “How do we replace the artistic director with a trans women of color who already knows what’s going on?”

That might be my own soap boxes along the way where I’m nudging people towards that. It’s part of the conversation of also realizing that none of these conversations are going to exist in a vacuum. We can’t be stepping up for trans and non-binary folks without also making our spaces accessible for disabled folks, and making sure that we’re also being really diligent about racial justice and avoiding those microaggressions. All of these conversations are overlapping. I think people come in with that narrow scope of “Okay, pronouns, or bathrooms,” or whatever they’re focused on. Then it’s like, “Ohhh! Dismantle capitalism. Let’s fight white supremacy. Okay.”

At least that’s my hope. That’s feedback I’ve gotten that people do have the wider view of the systems that these issues are taking part in, and that we can put a Band-Aid on pronoun usage, or we can flip the system and we can be part of the conversations where we don't have to look out for the marginalized people in the room. We can just make sure they’re no longer marginalized.

Nicolas: That’s a very—

Maybe: It’s not going to happen in 10 hours.

Nicolas: No, no.

Maybe: I like to say that it’s not a two-day conversation. It’s a 2 year or a 10 year. Everything I do is the start of a conversation. It’s trying to give people the tools and light a fire under their asses and be like, “Now go!”

Nicolas: Planting the seeds—

Maybe: “Fly!”

Nicolas: —in those 10 hours.

Maybe: Exactly.

Nicolas: Knowing what questions people should be leaving with.

Maybe: Right.

Nicolas: And how to start those conversations elsewhere.

Maybe: When you have directors and producers and writers and intimacy directors in the room who have power in room and have positions where they are leading a space, they’re creating spaces. They are in charge of emotional and physical safety in spaces. If they have those questions in the back of their minds, they can start building those spaces more intentionally and in different way.

They can start thinking about those things and being like, “Oh right, we had this conversation. We shouldn’t be using this language. What can we use? Who else might we be harming with the language that we use? How else can we move and shift the ways we’re going about these conversations, and not just play catch up because somebody got misgendered, so now we have to fix it.”

Nicolas: I think that leads nicely into my next question. What do you say to the cishet producer, director, teacher, who might assume that the practices, approaches, questions that they’re learning about in this class are only relevant in their work with trans or non-binary actors?

The person who says, “Well, we don’t have any non-binary actors in our program,” or those who say, “Well, trans actors just aren’t auditioning at our theatre.” I totally have never met one of these people. Obviously, this is entirely hypothetical. As a trans person who is also an educator I, of course, never come across one of these people who makes this assumption, but they’re out there. You know?

Maybe: I do know. That’s a conversation where I often tell people if a certain demographic is not auditioning for your season, your play, your whatever you’re doing, there might be a reason why beyond they’re not available, or that they’re not around. Leading with affirming practices can help to ensure that trans and non-binary people feel comfortable and safe and welcome in your spaces and in your stories.

Likewise, especially in academic settings, we do have a number of educators that come through, usually. There might be people who are trans or non-binary who don’t feel safe or comfortable telling you that because you’re not affirming. Because you’re not leading with the best practices. Saying that you don’t know any trans and non-binary folks, or you don’t have any trans or non-binary folks in your program or in your work, is usually probably not true. At this point, there usually probably is someone who doesn’t feel comfortable letting you know who they are or that they are trans or non-binary.

Likewise, especially in educational settings, I say this because young folks are usually navigating their identities for the first time, especially in colleges and time away from parents for the first time and all of those things. Even if there’s not anybody who's openly trans or non-binary in our classrooms, introducing the concept that there might be, might help some folks realize that they are. I discovered myself in a college class. We learned about what trans people were. I was like, “Oh, that’s what’s happening.” Like being able to—

Nicolas: As I learned like “gender is a social construct,” I was like, “Wait, I’m not just naturally bad at being a woman?”

Maybe: Right.

Nicolas: “There’s not something just inherently wrong with me? There’s just social rules?”

Maybe: Right. I think theatre classes specifically are such a beautiful place for people to be able to start navigating that. I think of all of the women in musical theatre I wanted to play as a kid and how they shaped the woman I am today; and how I latched onto those stories in a way that I couldn’t understand until I could put words to it, and I could put language to it.

If we offer people that language, they’ll have a better shot at feeling safe, and affirmed, and comfortable in their own bodies. Also, the idea that being inclusive or affirming is just for trans and non-binary folks, in any context, is complete bullshit to me. That being affirming of people’s experiences and genders goes way beyond trans and non-binary inclusion.

When I’m talking about affirming pronouns, in any context, I’ll often reference, like, I know a lot of cisgender heterosexual men who are going to get really mad if you call them she. You understand how important affirming pronouns are, you just don’t usually have yours used against you.

Nicolas: Yeah. It is one of the most offensive things that you can do is to misgender a cishet man.

Maybe: Right. That’s where I don’t think making any steps towards respecting or uplifting any communities is going to have an impact that doesn’t help everyone, unless that community is like Nazis. In talking about like marginalized communities where trans liberation is going to save all of us. The ideas of men being pigeonholed into very restrictive forms of masculinity and having to play these roles of “boys don’t cry” kind of things is the root of toxic masculinity. It comes from men having to do a thing that isn’t actually working for them. It sucks.

Nicolas: Yeah.

Maybe: Where if we ease up on those expectations and on those standards and stereotypes, we’d all benefit. That’s my soapbox answer to folks who are like, “Oh, I don’t have trans or non-binary folks in my program. That doesn’t help. That’s not going to be good for them.” Making sure we know how people want to be referred to is going to help everyone feel safe and respected in a space.

Making sure that folks are feeling comfortable in the roles that we’re casting them in, in the types of auditions we’re offering them, in the dressing room assignments that are being given. All of that is going to help everybody, even outside of gender and things like that. Talking about type, and stereotypes outside of gender. All of those things…none of this exists in a vacuum.

Nicolas: All right. A couple of questions that I’d like to ask before I let people go, there are two main theses of this entire podcast series. One is trans people are everywhere, as we have discussed earlier. Two, we have always been here. I like to ask folks, would you like to give a shout out to someone who is part of your artistic queer, trans family tree? Acknowledging that sometimes those things overlap; sometimes they don’t. All is perfectly fine. Who has inspired you, supported you, helped you get to where you are today?

Maybe: There’s so many. I could fill another half an hour with this response. I think the first that comes to mind for me is L Morgan Lee. I don’t know if you know her work, but she is a dear friend and a fantastic performer. Through our friendship, she has taught me so much about being genuine in yourself, and finding the work that is right for you and speaks to you. Outside of gender and things, she’s the kind of person who’s not going to go in for a role if she doesn’t want it. She’s not going to go in for a role just because the casting director should see you. I mean, she might sometimes, but she’s going to be who she is most authentically in any space and not try to play into a stereotype to get a role and things like that. That has taught me so much about how I approach a lot of these conversations and approach my own relationship to this work. She’s also just one of the sweetest, most caring souls that I’ve experienced in this industry, who is really looking out for the people she cares about.

Another, how you phrased the question was also talking about we’ve always been here and through history. I feel like I would be remiss if I’m not acknowledging the Kate Bornsteins and the Alexandra Billings who walked so that I could run and who blazed trails that I get to relax in. I’m going to New York next month, and I’m planning to see Alex in Wicked. The idea of me seeing a trans woman in Wicked, I haven’t seen Wicked since I saw Idina Menzel as Elphaba.

Going to see a trans woman play Madame Morrible, I’m just going to sob the whole time. I feel like Alex specifically doesn’t get enough credit for the trails that she blazed. People really started listening around Laverne Cox’s trans tipping point and things, but Alex has been here. She’s been out there.

Nicolas: She’s been around.

Maybe: She has a memoir coming out that I'm so excited to read.

Nicolas: I’m so excited about that.

Maybe: Yeah, because I’ve really honed in on really following and listening to her life and experiences, realizing Kate Bornstein is an example that I had for a very long time of a person who’s similar to my identity, who is doing similar work to what I want to be doing, but isn’t quite encapsulating all of it. Alex is a step closer. I’m realizing that, actually, that Alex is in the musical theatre game and playing roles that… Maybe I could age into Madame Morrible. That would be fun as hell.

Nicolas: Oh, that is such a fun role!

Maybe: I’ve always thought I was a Nessa Rose but maybe I'm a Morrible. Like, just thinking… Alex is a person who shows me opportunity and makes a space that I'm like, “Oh, I might be able to do that one day.” Actually, Alexandra specifically is like a flip side of the coin with L Morgan where Alexandra has played roles that she doesn't believe in and has done some shit, so that she could get seen. And so that I could know who she is today. She's played the tropes and she's done the stories. I respect her like none other because she knows why she's doing it, and she's using it. And she's leveraging it to get where she is.

That's yeah, there's like compromises we need to make in order to survive, in order to work, in order to get those platforms so that she can be the beacon of hope that she is for me right now. She can be in the spaces where she's writing a memoir that I get to read and sob through.

Nicolas: Final question. Could you leave us with an image of what gender euphoria looks like for you, either in performance, or in your everyday life?

Maybe: Hmm. I think they're both in the same, actually. There was a period of my life where I was actually playing into performance, and making that impact my daily life in terms of gender presentation and all of those things. There's a character in [my] play that is navigating a new gender expression for the first time. There's a monologue where somebody asks her how she feels looking at herself in the mirror for the first time.

She's like, "I feel fine." Then her friend's like, "Fine? Honey, if you don't get a high from a pair of heels, you're probably not cut out for this thing." That's what gender euphoria feels like to me. It feels comfortable. It doesn't feel like a high. It doesn't feel amazing. It's not this big, huge thing. It's just me feeling natural. It's not me feeling like I'm dolled up or putting anything on. It's me feeling like I'm doing what's authentic and right for me, even if it is in a gown and heels, right? Just feeling at home and feeling secure in that. My greatest senses of euphoria are when I'm feeling casual and whole.

Nicolas: Cool. Thank you so much for coming on to talk with me.

Maybe: Of course. This was such a fun conversation.

Nicolas: Yeah.

Maybe: Thank you for this.

Nicolas: Yeah. Thank you for listening. If you'd like to learn about Maybe Burke's work or the Transgender Training Institute, you can find links along with resources and some information on the other names and programs that we've mentioned today in the show notes. Make sure to tune in next week. I'll be talking with Siri Gurudev about queer, trans, color-produced theatre, and devising practices. Until then, this has been Gender Euphoria, the podcast.

Gender Euphoria, the podcast, is hosted and edited by me, Nicholas Shannon Savard. The voices you heard in the opening poem were Rebecca Kling, Dillon Yruegas, Siri Gurudev, Azure D. Osborn Lee, and Joshua Bastian Cole. Gender Euphoria, the podcast, is sponsored by HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here