Gender Euphoria, Episode 5: Queer of Color Devised Performance, Disidentification, and Spirituality

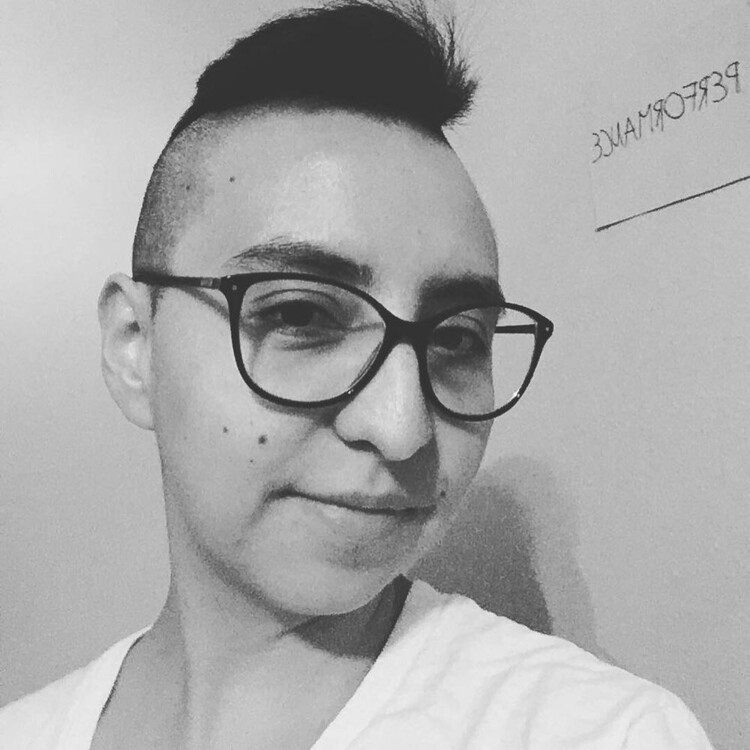

With siri gurudev

Nicolas Shannon Savard: Hello, and welcome back to Gender Euphoria, the podcast. I'm your host, Nicolas Shannon Savard. My pronouns are they, them, and theirs. This episode's conversation is with siri gurudev. I met them while I was doing my dissertation research in September of 2020, and then in February of 2021 we got to work together again when they performed a livestreamed rendition of their piece, Karla and the Deconstructed Cabaret and spoke on a panel about intersectional trans art, as part of a digital performance festival that I organized called Trans AND.

I was so happy to get to work with them again as part of this podcast. We talk about how siri's work blends queer color theory and performance techniques, devised theatre, popular music, and spirituality. We chat about their dissertation research into ritual, trauma, and healing in QTPOC performance. We explore questions of the artist's responsibility to the audience, especially when dealing with trauma in performance at the scale of the personal, the community, and the cultural. What level of care do we need to bring to our practices? siri shared such nuanced and thoughtful insights from their own experience in highly interactive activist performance, and I am so glad to have the platform to share them here.

So siri gurudev, whose pronouns are they, them, or elle, si hablas Español, is a multidisciplinary artist with a focus on experimental theatre and performance in the Americas. gurudev is a trans non-binary writer, performer, activist, and researcher from Bogotá, Colombia. Their work orbits around the questioning and destabilization of gender binarism, visibalization of racialized gender violence, and the quest of being a Mestizx from the “third world.” Can they connect with their indigenous ancestry while finding traces of queerness in the archive? gurudev holds a BA in philosophy and literary studies, a master's in creative writing.

The experimental sci-fi trans love story novel they wrote during that program, called The Future of Ismael, was published through Random House in 2017. siri is currently a PhD candidate in performance studies at the University of Texas at Austin. In the past year and a half or so, they have completed performance art and theatre artistic residencies at the Black Mountain Project, Ground Floor Theatre, and INVERSE in collaboration with the Momentary Museum. Their work has been produced by Generic Ensemble Company, Futurx Festival, and OUTsider Fest, among others. Let's dive into the conversation.

Rebecca Kling: Gender euphoria is...

Dillon Yruegas: Bliss.

siri gurudev: Freedom to experience—

Dillon: Yeah, bliss.

siri: masculinity, femininity, and everything in between—

Azure D. Osborne-Lee: Getting to show up—

siri: without any other thought than my own pleasure.

Azure: as my full self.

Rebecca: Gender euphoria is opening the door to your body and being home.

Dillon: Mmm. Unabashed bliss.

Joshua Bastian Cole: You can feel it. You can feel the relief.

Azure: Feel safe.

Cole: And the sense of validation—

Azure: Celebrated

Cole: —or actualization.

Azure: Or sometimes it means

Rebecca: being confident in who you are.

Azure: But also, to see yourself reflected back.

Rebecca: Or maybe not but being excited to find out.

Nicolas: All right, welcome to Gender Euphoria, the podcast. I am here with siri gurudev, solo performer, devised theatre practitioner, activist, performance artist. Today, we're going to talk a bit about queer and trans color produced performance and theatre. So, I think I'll start us off with the question, siri, how did you get into making devised theatre in the first place? What was your journey in getting there?

siri: It's interesting, because I started as an activist, and so I was interested in performance art mostly. There are very similar things with devised theatre in some of the processes because I wanted to use that as a tool for social justice, especially in Colombia, in Bogotá, in my city, to create awareness, and even stir up the pot a little bit with actions that were on the street or semi-scripted, but in public spaces. And so I started using that as like... well, me, of course, my collective of trans folk. We started using that tool to produce work around being trans. When I moved here to the U.S. I started to get acquainted with devised theatre. Also, for purposes of people of color critique, so it's pretty social-driven, I will say.

Nicolas: So your activism and performance is very much intertwined, would you say, between activism and the performance of it, and your own identity. Can you say a little bit about… because it sounds like you had a community around your different activist actions when you were in Colombia. Can you talk a little bit about what that looked like?

siri: Yeah, that was ten years ago, so things have changed for good a lot. But at that time, only trans man group. The non-binary idea was not around and so I identified as trans at that time just without any other addition. And we were working around popular music, and a lot of fun and comedy stuff, and it was like a small group of people.

Today, we have multiple trans men groups and nonbinary folks are involved, and it has grown, of course. But at that time, it was tiny, sweet, and problematic at times of course, group of people that I'm really grateful that I got to know for some years.

Nicolas: And you're still doing some things, kind of interrogating popular music. You were in the Trans AND Digital Performance Festival that I organized in 2021 in February, that feels like so long ago right now. But I got to see you do Karla and the Deconstructed Cabaret where there was a lot of singing, there was poetry, you had sort of a drag persona. I guess, how have those different elements kind of progressed throughout your performance career?

siri: That's a good question. I learned the methodology of taking popular music and rewrite the lyrics with my collective. They taught me that, they wanted someone for the group and I was just like, “I kind of sing, I kind of dance.” So I joined and I learned. Of course, it's so simple and I've seen it a lot where you just rewrite the reggaeton (mostly) music that we were doing because it's very misogynist and transphobic and everything. So that was one element that I pulled for ten years to now where I also—because we're very… in Bogotá we're very intertwined with the sex workers and the trans women sex workers. And they have these amazing drag shows where they not necessarily change the lyric, but they would; with their bodies, they are telling you another story, different from what you hear, right? And that actually a cover is pretty much like that, to engage with a traditional song. I mean, if you want to make it a twist, give it a twist, you just do it with your body.

So I kind of brought these two things where like, “Oh, I think I can rewrite songs.” And also, if I just do a performance that goes in a criticism of the lyrics, I also can create the same effect. So now that I say, just dress as Karla and others and do that. Yeah.

Nicolas: Very cool. What is your devised theatre practice looking like more recently?

siri: Mmmm...

Nicolas: I was going to say today, but I'm sure it looks different “today, today” with the ongoing pandemic than it did in 2019.

siri: Well, I learned about some techniques for devised theatre with Generic Ensemble Company here in Austin, which is directed by kt shorb, a very dear friend of mine. And interestingly enough, what the company does mostly is devised theatre, but they come from a traditional piece and they rewrite it in a devised process, which is exactly what I was doing with my songs.

And so they took Carmen or Scheherazade, and they rewrite it with a group of people. So for me, that was just a perfect place for me to connect things that I'd been doing and learn more. And so now what I'm trying, because after a lot of work with groups, I started my solo project, right? And so for me, it's been an invitation to start working again in a group setting where, well in GenEnCo (Generic Ensemble Company) I was an actor, but now I'm trying the directorial, the director's hat, and see what happens. And so for me now, I'm starting to gather collaborators and tell them to offer, “What have you written lately? Tell me, what is your last poetry?” And see if I can thread things through that. Because we cannot be together in a room doing exercises and stuff to devise something in a more traditional way. So what I'm doing now is trying this out of inviting people, and let's see what you have and try to connect things and so...

Nicolas: Cool. With Generic Ensemble Company, what did the process look like of kind of taking those more traditional texts and rewriting them?

siri: Well, it's interesting because we would see the piece together and trash it and be like, “This hurts, this is bad.” And then make it our own as a way of, well... people of color critique and stuff like that, where you can just engage. And then of course for me, there's a lot of like, why would you engage with the classic? Let's just do new stuff, right? And so it's this negotiation right. Then, same with me. Why don't [I] just write my own reggaeton music, right? And so I think I go back and forth because if I write my own, no one cares, no one knows it; I'm no one. But if you engage with the pop thing, the popular thing is really powerful. So there is something there, right, that you want to tap into when you're criticizing or showing the flaws of the thing. Yeah.

Nicolas: It's kind of like already—you're joining a conversation that's already happening.

siri: Exactly. Yeah. Whereas starting [with] your own voice is harder.

Nicolas: Yeah, yeah. The process you're describing reminds me a lot of José Esteban Muñoz's disidentification, of working on and against existing texts or just cultural stereotypes, and cultural narratives, and things like that.

siri: Yeah, 100 percent. I named one of my methodologies as disidentification, definitely. When I read that I was like, yep, this is what we've been doing for sure.

Nicolas: Okay. I want to pause for a quick overview of some of those terms. First, queer of color critique. Queer of color critique, as a phrase and as a method of cultural analysis, is often credited to scholars, José Esteban Muñoz and/or Roderick Ferguson, depending on the academic discipline. It was developed in response to the growing field of queer studies in the late 1990s.

Queer studies, especially at that time, was pushing to generate theory into discourse that could be used to analyze sexuality… but sexuality alone, disconnected from race, gender, or class. As a result, we had a lot of theory written by and reflecting the experiences of cisgender, white, gay men. Queer of color critique, as a framework for understanding politics and culture, suggests that if we are to understand queerness and the social, political and economic issues queer communities face—if it's going to actually include all of us, that is—we must use an intersectional approach, which explicitly acknowledges the context of racial capitalism and a white supremacist culture and state.

With that said, Muñoz and Ferguson may have been the first to publish books using that term specifically, but they were drawing upon theories articulated by women of color activists and scholars, dating back to the 1970s and 1980s. Folks like Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Cathy Cohen, the Combahee River Collective, and other Black feminist groups were laying the groundwork for queer of color critique, before queer theory was even a fully established line of thought in the Academy.

Okay, term number two: disidentification. Queer of color theorist and performance study scholar, José Esteban Muñoz, coined this term in his 1999 book Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Most simply he describes it as, “The ways in which identity is enacted by minority subjects who must work with/resist the conditions of (im)possibility that dominant culture generates.” Muñoz found the concept particularly useful for describing the cultural and political work that he witnessed artists creating and performing in queer of color community spaces. It's a way of performing and grappling with both personal and shared identity, when you're living in a culture which marginalizes people like you.

He writes, “Disidentification is a strategy that works on and against the dominant ideology. Instead of buckling under the pressures of dominant ideology (identification, assimilation), or attempting to break free of its inescapable sphere (counter-identification, utopianism), this working on and against is a strategy that tries to transform a cultural logic within, always laboring to enact permanent structural change, while at the same time valuing the importance of local or everyday struggles of resistance.” End of quote.

The crafting and subsequent performance of identity through this strategy might look like reclaiming or rehabilitating stereotypes and cultural images—or in siri's case, popular reggaeton songs. It might look like envisioning and rehearsing new social relations. Disidentification offers a useful lens for understanding trans and queer of color art and performance because for many of us a major goal of the work is to intervene into popular narratives, to place our own lived experience in dialogue with broader cultural conversations, and to redefine for ourselves, and for our audiences, what queerness and transness can mean within the context of our own lives and communities. Okay, back to siri.

I'm intrigued by this process of taking these kinds of classic stories and texts and tearing them apart in order to rebuild them in a way that you can actually see yourself in it. Sounds like it would be kind of empowering, cathartic um...

siri: Yeah.

Nicolas: You get to write yourself into these narratives that have historically excluded people like us [and] queers of color… There wasn't a question in that, I don't think.

siri: No, but I totally see what you're saying. It does feel good, yeah, and empowering. And sometimes we just need to say, “Hey, this mass cultural product is hurtful. This is why.” And then I need you to see that it hurts, and then I'm showing you why with humor, and then I'm showing you also another way to tell this same thing. So I feel like it has its good stuff there.

Nicolas: Yeah, like kind of rewriting the narrative.

siri: Mmmhmm. Which is actually, if you think about it, is a lot of historian of color methodology. We are going, visiting the archives and saying, “This is not exactly… let me just be critical about it and tell you another narrative based on also, actually, what is not in the archive, the little holes that we have.”

Nicolas: So I know you've been part of pieces that you've directed, written, devised with a group. The name that we talked about during our interview is escaping me, but you had an all trans cast—

siri: Oh yeah.

Nicolas: —that you did. Remind me what it was called.

siri: Yes. So the director hat is very recent, so those are like my last two projects, but I've been part of two shows that are fully with trans non-binary folks. One was TRANSom, which was directed by Jesse [O’Rear] and Lisa [Scheps] at the Ground Floor Theatre. And the other is the script that I wrote, The Future of Ismael, was produced by GenEnCo, with a cast that was trans and non-binary people, and was directed by kt [shorb]. I was the writer for that.

Nicolas: Okay. So in working in contexts like that, with all queer people of color or all trans and non-binary people, how did that sort of rehearsal space and creative process look different from other processes that you've been a part of?

siri: Oh, it's really special. But also you can see how intersectionality, it's real. Because for me, for example, in one of the experiences, there was not many people of color, but we were all trans. And so there were amazing things that we can share, the confidence and safety of being all of us trans, was great. And at some moments I felt like no one could understand like, how does it feel for me as an immigrant, as a person of color from Colombia. Because I was the only one that in that cast that was not English as my first language, native language. And so I feel like that was some moments where we cannot connect so much.

And then when I do my director projects, it's Latinx folks, but there none of them are trans, and so we share that we speak in Spanish and it's just this familiar feeling. And also on some moments, they just cannot connect so much with my gender identity. But I feel like it's so rich and it's so good. And it's hard that I would only ask for being exactly people like me all the time working with me, because also in the differences, I can notice things like privilege that I have, privilege that I don't have, things that I need to work on because we're diverse. And so… but the experiences have been really healing, I must say, really good. And I'm looking forward to having more of those.

But also I was talking with a friend and they were telling me like, “Oh my God, it's been a long time since I’ve acted with a cis dude.” And we were like friends, we were like bonding, and it just feels great to have these other people that I never interact with because that's—we queers, that we like try to be a little, you know, because we're trying to feel safe. So I feel like it's so many different aspects of it, but it was really healing, the experiences I had. Really good. Yeah.

Nicolas: Cool. And you are working on a dissertation looking at healing in queer performance and ritual. Can you talk a little bit about that project?

siri: Yeah. So as I started my spiritual journey, I started to feel that I needed to unify myself because one persona that I had was this performance artist that is a little edgy, that does striptease and stuff like that. And then I had this other part of me that was like a monk. And so I was doing very deep rituals and spiritual, less embodied things. And I was just like, “This seems very separate, but it's not. I need to just find the place where it just comes together.” So I started doing work, performance artwork that were mixing the two of those things.

And then I was just like, I want to do research on this. I want to see performance, in Latin America and the U.S. mostly, where people are combining spirituality and performance, but it's not like the classic anthropological thing where you go to an organized ritual and observe. You literally… art that has spirituality embedded. And that, for me, when I see the pieces, I feel like a spiritual something going on. And so I'm really interested in that place where those interact. So that's what I'm researching on.

Nicolas: Cool. What sorts of things have you been looking into? Are there particular artists, companies?

siri: Yeah, I have some case studies with artists, and then I'm very interested in their methodologies and how their spiritual background sort of comes into play. So, just to name one, I'm looking at Asher Hartman, which I'm obsessed with. And he learned from the spiritualist church and the Fox sisters, so to be like a medium slash channel, and so he puts that into his work scripted and his devised practices and everything. And so, I'm like obsessed with him and his company, and that's one of the examples that I'm studying right now.

Nicolas: Cool. How does the sort of ritual and spirituality and healing practices show up in your own work? Because I saw that quite a bit in your performance with Karla. How does it show up in your other work?

siri: Yeah, I feel that it's in different ways, in the form of the performance it does comes in, like the ritual part, but actually in the intention to create a piece it's already my spiritual intention there. So for example, for Karla, there was a spiritual attempt to put forward my codependency and my romantic not healthy patterns and put them on display to transform them, right?

And so that was the force that gave me the impulse to create the piece, plus the other things. And then in the performance itself, you can see some ritual going on. And so I feel like other works I've done have also this intention of, with humility of course, like what do I want to transform here? So that would inform how do I create this piece and how I invite people to join me in this journey, of this ritual slash performance that I'm creating.

Nicolas: What are some of those ways that you find to invite people in to join you in that journey and transformation?

siri: So I've been trying different things. And I feel like when I was younger I was a little less aware of the impact, but I'm really interested in moving people's emotions, and especially I connect a lot with sadness and despair. So one of my first pieces that we mixed spirituality and this was like six years ago or something, and I invited people to do a sort of a choreography where they would do a movement or a phrase remembering one of the wounds that they have from the patriarchy. And we would mimic their gesture back at them trying to put it out and, again, heal it. And so—but that is huge, like, if you know? So—and they can use words as well. And so, one of the moments where like, “You're a bitch,” or something, and we were like all screaming out, “You're a bitch." You know, so strong.”

And I remember feeling like I have this responsibility that I have put these emotions here and I have to be aware and know my limitations because I'm not a therapist… yet, maybe in the future. And so, I feel like that was a little more like taking this risk. And I think now I'm a little more subtle maybe, or I'm more aware of the care process and the care that I can offer to my audiences. But I still feel like I'm getting [an] emotional release, which is funny because it's like the most classic notion of theatre is just catharsis, right? But it's been a long way, and it turns out it might be something real.

And so I remember with the piece that I did for the festival that you organized, I think Penny [Sterling] was saying, “Yeah, like I was really uncomfortable at moments and like seeing you dealing with this like penis-serpent-kind-of-thing.” And you know—so it's like a lot of how can you really be present and aware of what you're doing, when you're dealing with emotional stuff? So yeah. I feel like it's a fine line there, but I'm trying my best for sure.

Nicolas: Yeah. I think that is something that comes up in a lot of queer, trans, and queer of color performance, is that we are kind of also in this space of healing and also processing trauma in performance because we're just—unfortunately, we live in a world where that is a lot of our experience, and that is what's reflected back to us on stage and on screen and in pop culture.

And you talked a little bit about how you're not a trained therapist and yet leading people through these emotional journeys in your work, because this is something that I struggle with too, in my own work and devising and applied theatre working, especially in community and the closeness like this, how do you kind of balance and draw those boundaries? Like, this is something that we're equipped to deal with in this space and support each other through versus this something that is beyond me?

siri: That's such a great question that I think it should, well for me, it should be the one that guides my practice. If I had that question in my mind things would be better than if I don't have it, right. And so I feel like for me, there is some sort of a spiritual conceptualization of a piece, where I see that there is a moment where I put the invitation to the emotions to come up, and then I design myself ways in which I am hoping to offer some sort of transformative feeling, or some way of “going to the light” kind of thing. And it sounds linear and it might be but I feel... when I'm creating a piece I'm having this awareness that we need both, and it's a balance. Sometimes we’ll start with the light and end with the darkness, to say. And sometimes it's the other way, but I feel like I have to bring both.

And when I was doing this [when I was] younger, I would just put out all the shit, right, and not be responsible for that. And now I feel like I'm trying to see both, also knowing, again, that we have limitations, and that sometimes people just need to cry and there's nothing else, right. I cannot make you laugh afterwards and feel great. So like it's a little bit of feeling that this bubbly, like [woo sound], is not necessarily the spirituality that I'm looking for; it's not all roses and sky. There is a lot of spiritual work in actually acknowledging what people call their shadow or their hard stuff. So I feel like it's a lot of, for me, a lot of personal work needs to be first. Then, after, I would offer. Right? So I need to really work on myself and have this clarity and then I would create, so that's kind of how I see it. Yeah.

Nicolas: Cool. So something that is striking me here is we're holding queerness and transness and spirituality at the same time in a lot of this conversation. That doesn't really reflect a whole lot of our cultural narratives, which tend to frame queerness and transness and spirituality as really adversarial. How have you found working with those two things in conversation with each other?

siri: Well, I feel like one of the things I've done, especially in my last piece, In the Name of the Father, was criticizing the organized religion, in this case Catholicism, that has condemned us. And so there is a work where, if I'm going to offer spiritual connection to my queer and trans folk, I'm telling you also I'm aware of how much this has hurt us, and that's not what I'm doing. This is not the Catholic religion thing, you know. So to show that we all as humans, and this is my belief, we have a connection with the divine, we have a connection with whatever it is [that’s] bigger than us. And it doesn't have to be connected to an organized religion or ritual. And so I feel like part of it has been for me to criticize and acknowledge where I'm coming from. I was raised Catholic and these [are] the problems that I have seen. And this is other stuff that is good, that when I'm scared sometimes I recite psalms from the Bible, right. And a lot of spiritual churches use the Bible. So it's this way in which, again, disidentification, right, we're taking what is good and leaving what is not. And so that you can have a responsible offering to others that are hurt by religion, let's say. So I feel it's different, very different; spirituality and religion, two different things.

Nicolas: That's a good distinction to make, I think. Right. So before I let you go, I've got a couple of questions that I like to close with. So one of the main theses of the series is trans people are everywhere, and we have always been here. So would you like to take a moment to shout out someone who is part of your queer-trans-artistic family tree, someone who has inspired you, supported you, helped bring you to where you are?

siri: Yes. So I mentioned kt shorb and I will re-mention them. Definitely a really important figure in my life academically, artistically, and a friend. And Sharon Bridgforth is also a big, big one for me. I've met mermaid’s work and cry and laugh with them. It's really healing. And so I also feel a little bit connected to Sharon Bridgforth, for sure. I think that was my two picks for now. Well Asher Hartman, I was also telling you about Asher, and although it's a recent discovery I'm so into him and his work that I feel like it's already informing my own practice for sure. So those would be my picks.

Nicolas: Fantastic. I will link in the show notes where you all can find all of those fabulous artists. All right. And finally, could you leave us with an image of one way that you experience gender euphoria in performance or in everyday life?

siri: Mmm, that's a good one. Yeah. So my connection with femininity, as for many of us, is really complicated. Sometimes we're like, “I am not whatever that is.” And then it is, “Well, wait, how, what, maybe I am a little bit—what parts of me feel connected to femininity?” And lately for me with this persona, Karla, this drag persona, I've been experiencing femininity as I grew up knowing it, with I am deciding to, not I'm forced to, just those ideas of femininity that are a little more mainstream. And I'm enjoying that so much. I feel that is safe, that I can just play with it, and so I'm having my long hair, my lingerie, and all those things. It feels weird because it's like coming back from whatever assigned me to at birth, but it's not, it's like a whole different turn with a different perspective that feels pretty healing. And so I'm having my time with Karla, and that gives me gender euphoria. Yes.

Nicolas: Karla and healing; playful femininity. I love it.

And thank you all for listening. If you'd like to learn more about siri guruduv's work, you can follow them on Instagram and also check out their website, which is linked in the show notes, along with links to more information about the various artists and performance collectives and books that we've mentioned throughout our conversation. In the next episode, I'll be talking with Rebecca Kling about the ways that her work as a solo performer has informed her career as a trans educator and advocate, and her rather unconventional, evocative—well I find it hilarious—approach to the postshow talkback. I won't say any more about that now, you'll just have to listen to find out. Until then, this has been Gender Euphoria, the podcast.

Gender Euphoria, the podcast, is hosted and edited by me, Nicolas. The voices you heard in the opening poem were Rebecca Kling, Dillon Yruegas, siri gurudev, Azure D. Osborne-Lee, and Joshua Bastian Cole. Gender Euphoria, the podcast, is sponsored by HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here