The How of Theatre

a Playwriting Class

I consider a large part of my National Playwright Residency Program residency at Marin Theatre Company to be the continual asking and answering of this question: Why theatre? This series of videos will be a collection of asking and answering that question in myriad ways. I will ask myself, my fellow theatre artists, social scientists, and community leaders. Sometimes the answer will be cultural (because art is good for you!), sometimes technical (because story has universal dramatic structure!), sometimes biological (because narrative is an ancient element of our human evolution!). I believe that it is the energetic and open asking and answering that keeps our art form relevant, responsive, and inspired.

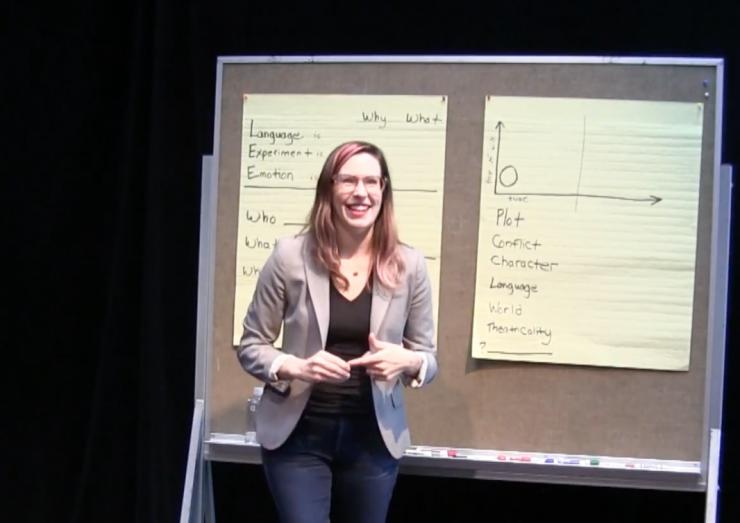

This tactical class focuses on dramatic structure, building characters, and crafting a powerful ending to your story. I try to give beginning and experienced writers alike an overall picture of dramatic storytelling works, how to push it to the limits, and how to make sure the audience walks away emotionally moved.

Video editing by Jeff Berlin.

Transcript:

OK, I wanted to start this class about structure because, again, as with all of these elements, we're all talking about the same thing as we kind of break it apart in its pieces, it doesn't work without the others. When we talk about story, we're talking about character, and plot, and all that other stuff. Of course we are.

I think it's going to help us to back up. As a way of analyzing the stories that we're already in the middle of, whatever draft we're on. Coming up with stories, deciding about which stories to proceed with, to really back up and figure out why story? What is it? Why do we tell them, and even further back, why art? Why do we make stuff up?

Why do we paint things that are already there in reality? What is this thing that human beings, over and over, across time, across culture, we fictionalize. We create stuff. We're not satisfied with reality. Why? When I back up, I start to see elements that can make plays absolutely unforgettable, iconic, necessary.

When people come to them, they go, "That is me. That's what I need," or, "Oh my God, I don't want to be that." I've been certainly conscious of it in the last six months, but for many years I've been figuring out why do we do this? I love it, and I'm not going to ever stop doing it, so if the answer is just because it's fun, I guess that's OK, and thus my career is just having fun. That's fine.

It's way more than that, and we all know it's more than that. I want to start, actually, in the most universal way we can, as we dig down into your story, your play, those moments. What's important for me is figuring out where this all comes from. What I realized, because of some fabulous science, but also a ton of just intuition, is that we make art because we need to organize, and categorize, and explain, and understand, and find a sense of coherence to a chaotic world.

As they say, story is life with all the boring parts cut out. That's why. Because a lot of life is confusing, tedious, and stories aren't. If your story is confusing and tedious, I would suggest maybe you're in the wrong profession or hobby. If that's the point, is finding coherence, finding a way to understand, then that, again, just that much tells us what a good play needs to have in it.

It needs to have a question that we are trying to find some coherence, some meaning to, and by the end, we're going to get some piece of it. We're not going to have the world figured out, but we're going to have some learning. Something will have been learned. The other thing is, we are the highest element of social species on the planet.

We need each other. We are obsessed with each other. More than any other creatures, we want people. We have to understand them. There's a magnetic draw to each other. That's why we're going to tell stories about people, and why theatres specifically, even more than film and TV, which of course has people, there are live people in front of you. That's the heart of its magnetism.

We can't, like a light, you just can't not look at it. Why? Well, because again, to find coherence, we're trying to figure out how to do this life, how to do it well. If the base level is survival, and then once you've figured that part out, we can go to the luxuries of how you have a fun life, how you have a meaningful life, how do you find satisfaction. All of this has to have a people component, so your stories have to be human sized.

Even if there are Gods in them, those Gods are people. They're personified, right? This is what theatre all begins with, the Greeks, where we see their Gods. Their Gods would walk on stage, and have a monologue before the beginning of Trojan Women. Again, it's human size. We are looking for this coherence, but it's a coherence that we can swallow.

It is a coherence that is our shape and form. Something that we can do something about. It's not this kind of coherence that is so universal that it is outside of our parameters in any way. It's something that we can ponder, that we can grab a toe of.

Most of all, story is how we learn. Everything that we do can be put together in a story. What we are learning, what we are trying to find from the story is, again, this coherence for how to have a good life, how to survive, how to find satisfaction, how to find meaning.

Every story we can approach is either how do we love, how do we survive, how do we protect ourselves or others, and then, of course, we can get more and more complex. As the world changes, theatre changes, and our answers becomes a little bit more like well how do I manage loving two people at once? It's quite a luxury, but some people are like, "I can't even begin to think about that problem, much less a solution."

Of course, now we have so many of our Twentieth Century plays, or something on that line. All of it is going what would I do in that scenario? That's what we're posing over, and over, and over again. If I were there what would I do? If I were Hamlet, and I knew that my dad was murdered by that guy, what would I do?

If it were me, I would probably just go in a corner and cry about it. Not do anything because I'm scared of conflict, but if you're Hamlet, you ponder the great questions of life. You attempt, you try to catch them. You try to punish them, but he just confessed so he's going to Heaven if I kill him now. OK, I'm going to wait. I need to really punish him. Thus, one of the great western dramas is born.

The question of what would you do is the heart of every single play, so if that's a question that can start ... That's one of the elements that we will discuss once we get there. We will discuss one of the core dramatic elements that you have to have is a question that somebody in the audience can go, "Oh man, what would I do? I don't know."

You'd think that somebody would only be able to do that if the person is like them. It's actually not true. You don't have to actually have anything to do with that person. They don't need to look like you, be in the same time period, resources, class, race, anything. Human experience is human experience.

Again, this is why, when we look at plays, we are just following the people. We connect to their personhood, not the specifics that would align them in any other way. One story about this that I absolutely adore, and kind of illustrates this is I always talk about Hamlet. I'm obsessed with Hamlet. It's such an incredible story. The four of you have been here three times are sick of Hamlet by now.

I was talking with the great social anthropologist, Jared Diamond, over dinner once, and I was asking him, he's a mentor of my husband's, and I was asking him like, "OK, you ..." His specialty is ancient cultures is Papua New Guinea, so I'm like, "All right, so tell me about story. What do you see when you talk to them?" Just this one group out of many. "What are their stories like? Is there a pattern? Do you see these kind of great, great archetypes or mythology?"

He was like, "No, I don't actually. They don't really tell many stories that I know of." Then, he starts, "Well, there's this one time where a hunter that I knew really well was talking about ..." The only time I really saw him get emotional, he was saying that a lot of the times that that culture isn't as grounded and emotional or openness about emotion.

"He was really upset because somebody had killed his father." I was like, "Go on." He was like, "He wanted to do something about it. He kept trying to confront him, and to kill him." I was like, "So Hamlet basically is what you're saying? So Hamlet, great." Yes there is a pattern across ages and cultures.

We have an issue, and again, what would you do? That is what this person with no access to the great cultural icons that we have. He was processing the exact same thing that this fictional Dane of the greatest playwright in the world is processing. Something about that, there's a commonality. It is, in fact, that commonality that makes me love theatre evermore in this crazy time period right now. We are so much more alike than we are different.

No matter where you go, or who you voted for, we're actually dealing with the exact same stuff. I think that as part of the super powers of theatre, as a bridge. That's a bit beside the point, but just to put that out there. You're all super heroes for being here.

OK, so what I want to talk about for a second in this biological space of like why here? We need to learn, we need to connect, we need to understand. I was thinking about this. What are some of the elements of story that make it so valuable? The things that we pay attention to are people, we just talked about that.

They're just the magnets. The other thing we pay attention to is pattern. This is actually true in paintings, in music. We are paying attention to people and pattern. Frankly, where these two converge, and specifically where patterns start to break and shift, that's a story. These two are actually just it.

If you have people or personified characters, Gods, you can have a rock that's lived with another rock, and that's fine too. Inherently, they're having human emotions. The pattern, this is going to relate to structure and how we put this down on a page, it's where these two things come together. That's story.

Over and over again, we're going to have to figure out why these people, and of course all the things about humanity, what you want, who are you? What's in your core? What defines you? What are you terrified of? What do you think is beautiful? All of those things are going to funnel into this story, or give you the ingredients for just unforgettable characters.

Pattern is where we're going to find this plot, this continuous engine. The pattern, beginning of the story, right? There is a pattern set. The world is the way it is. The sun rises. The sun sets. That's actually not interesting as a story. It's where that pattern breaks, where the sun doesn't rise for one day. What? OK, now I'm paying attention. That pattern is broken.

That's just survival, right? If the bees all go to one tree, the people pay attention, and suddenly they find this amazing source of rich, sugary honey that can sustain you in your primal form. If you keep getting attacked by a tiger because you leave your waste outside of your hut on the wherever you are. You're going to figure out how to break that pattern to save yourself.

That's why pattern matters to us. It either helps us or can protect us. This is basic level humanity survival, animalistic stuff. I think if we realize that's what's at the heart of stories, how we tell them, why we tell them, and how we tell them that way, then you can really tap in to those essential feelings. That's why we're here is to feel the kind of like, "Whoa, this is universal."

This is what it is. People and pattern make a story. That's just kind of, again, primal stuff. The other ... Oop. Pattern broken. The other things that are going to become obvious, that are helpful to think about in terms of this, the primal elements. What just interests us?

We have beauty. A lot of these are kind of Aristotelian, but again, good to think about. You don't need all of them, well, you need these two in your story, but all of these you can have at different levels. Beauty, for one, and of course beauty is in the eye of the beholder, as they say, so it's very different, and can be changeable.

Grandeur, things that are so important. It doesn't necessarily mean size, but it just means a sizeable impression. Extremes, we don't look at the middle of a beautiful mountain, and are like, "Oh, that's gorgeous." We look at the top. What's going on up there? How high does it go? What's above that? How do we get there? The extremes.

We need bests and worsts. Again, if you're thinking of this in terms of pattern breaking, and in terms of education, we need to figure out how do I get the best, and how do I avoid the worst? That's what Oedipus Rex is teaching you. Like, "Yeah, you're the king, best. Yes, you did all this awful stuff, and you couldn't avoid it, worst, and you poke your eyes out, so you don't want to do that."

Extremes are very important. The other thing is uniqueness. Things that are striking, that are extraordinary because of the kind of solo aspect. What makes them pop out. Again, this is a reference to pattern. What is so different about this person, this thing, this moment? It can be unique for the universe. It can be unique for me, or this room, but all of those things are going to affect. Obviously, we would pay attention to that if we were on the savannahs of ancient times.

Thinking about these things, the other thing, of course, which I can kind of ... It's hard to categorize because they all kind of come in together. We were also obsessed with horrible, awful things. It's the train wreck symptom. Of course, again, thinking about it in terms of we are obsessed by people because we empathize with them. We'll talk about empathy in a second.

We are obsessed with extremes, uniqueness, pattern-breaking. Awful things tempt our eyes because, again, we're learning how do I not get there, and if it can't be avoided, how the hell do I survive? This, in terms of an extreme, that's going to make for addictive story telling. Again, it's hard knowing the way the world works now, and the way the media works now, and all of that, but we have to honor the fact that we have evolved to pay attention to the awful.

Now, in the world of theatre, it doesn't mean put a nuclear bomb on stage. I guess you could, but it just means that we can handle the worst. We actually want to see it because we are, again, biologically, we just, we have to, I just need to see, so I can protect myself from it, so I can know how to avoid. Yeah?

I wanted to interject.

Yes.

I teach Shakespeare, and right now we're working on Lear again.

Oh great.

You know you read about Lear, and it's so awful, and it is one of the most popular plays to be [inaudible 00:15:41].

Exactly.

I never thought about it this way. It contains all of this.

All of it. Every single one.

[crosstalk 00:15:47]. Yeah.

Every single one.

Every single one.

Even a natural disaster. It has a storm in the middle of it.

Right.

The worst of our ... I mean Lear is so great, partly because the metaphor is both external and internal, or they metaphorize each other, so the idea of his madness descending is uncontrollable and extreme, and thus the storm in the middle when he is at his worst is uncontrollable and extreme.

Terror can be a betrayal by your family. It can be a horrible mistake you realize too late. Spoiler alert, the end of Lear. We also have beauty in it. Cordelia, the purity, and the insistence on, "No, I'm not going to play that game. No, I know what's right, and I'm going to ..." Oh my gosh, it's magnificent.

Yes, the grandeur ... This is why Shakespeare, the stakes are so high because everybody's a king. Write this down. It's not just him, it's about the kingdom, the country, the future of the people is at stake. [inaudible 00:16:45] manifested in that person, which is again, people sized.

We can talk about madness and corruption, and it can feel too big to get a hold on. If you manifest it in a person, literally manifest it in Lear, now we can have a story, and we can have our own minds go, "What would I do," most importantly, and then the artistry of metaphor, where we get to play with, "Oh man, he's not just going mad, the whole kingdom is falling apart. Nature is rebelling. Again, this beautiful moment of the storm. Put a storm in your play. It's a perfect metaphor for everything. Yes.

OK, so there will be more, and if you think of more [inaudible 00:17:28] we'll put them on here. This is kind of why story, why art? I did want to stop for a second. This is actually a fabulous and fascinating book called Art is Therapy. I had it on my shelf for a long time before I read it, but as I've been recently really interested in this question, Why theatre? Why story [inaudible 00:17:48] art?

This boils it down into a really interesting set of principles that I think can apply. I'm sure you can relate to, as well as I can. I just want to read them out because they're so smart. This is actually mainly not about drama or a [inaudible 00:18:06] story. It's mainly about art, visual art. It makes perfect sense, and I think you'll see why. Again, thinking of this as creators, you could figure out, in your play, do you have one or all of these?

Do you have moments that your play can jump in here? That's the beginning of going, "Oh, this is going to matter to people more than me. This is going to start to be a universal story." OK, so chapter title is literally, What is the point of art? There are seven scenarios that are basically human feelings that art is a corrective to.

I'll read both. One, "We forget what matters. We can't hold on to an important, but slippery, experience, so art is a corrective of bad memory. Art makes memorable and renewable the fruits of experience." We forget the good stuff, and we forget the depth of the bad stuff. We need to see it over and over. We need to see Lear over, and over, and over to remind ourselves about family, and power, and greed, and also absolutely extraordinary love.

Two, "We have a proclivity to lose hope." True, totally true. "Art is a [inaudible 00:19:24] of hope. Art keep pleasant and cheerful things in view." Also true. We have a clown in every one of Shakespeare's incredible tragedies. I think drama particularly doesn't just have a stream of hopeful things. We like the kind of contrapuntal experience of having little hope, little sorrow, little hope, little sorrow.

It's true. Think about what is hopeful in your play. Doesn't necessarily end with unicorns and Frappuccinos, but it can be something that makes us go, "We're going to be OK. There's a way through," or "Because of this awful thing we've gone through, there's a way through."

At the end of Lear I often feel that. Damn, we've been through that. At least everybody learned not to be Lear, so that's good news, and we Sally forth with that, right? OK, three. "We incline towards feelings of isolation and persecution because we have an unrealistic sense of how much difficulty is normal." It seems to be opposite of what we just heard. We feel isolated and victimized because we don't know that a lot of that is normal.

The things you go through as a human being is hard stuff at every turn, and there could be sorrow, but that is why art is number three, "A source of dignified sorrow." That you're not alone when you lose a parent, when you lose a child, God help you. When you're in the middle of a war, and can't get out. You voted for someone, and they didn't win.

There is a source of dignified sorrow in the theatre, and I actually think that's one of the absolute super powers of plays. I kind of have a bit of an obsession of how you approach death with grace and dignity, and a sense that you mattered. It addresses that exactly. This idea that we can approach the most sorrowful thing, the most terrible thing, and theatre can let us go inside, and not just in a greeting card kind of way, like, "You'll be fine."

No, we're going to go in there. We're going to use that magical empathy of theatre, and you're going to sit right next to that person, in the same room with them living it, breathing, and we get to go, "OK, they're getting through it. I can see the other side with them." Even if they don't get through it, you can be there in your heart, and go, "OK, again, what would I do?" It makes you practice for the terrible, and the sorrowful, which is a good day's work, I think.

Four, "We are unbalanced and lose sight of our best sides." That's fabulous. "We aren't just one person. We're made of multiple cells, and we recognize that some of them are better than others, so art is a balancing agent. Art encodes with unusual clarity the essence of our good qualities, and holds them up with our bad."

Again, what's a great character? If they are only one thing, super boring, useless on stage, going to be cut out in the next draft. If they are at constant war with themselves, yes I believe in justice, but I also just want all the money for me and my family.

Yes, I believe in the, I don't know, whatever, but you're going to have exactly the opposite at some point in your life, or constantly in your life. It's that push and pull that art can put in front of us, and actually say, "No, that's normal. It's actually totally normal for you to be conflicted about all of these things."

Five, "We are hard to get to know. We are mysterious, even to ourselves, so art is a guide to self-knowledge. It can help us identify what is central to ourselves." That's that key what would I do question. You're going to figure out, or begin to answer it in a play. If the person you love doesn't love you back, "OK what would I do? Do I care about somebody else's love? How would I be able to release myself from that? How do I tell someone I love them?"

All of these things, you'll start to answer for yourself as you go through romcom or something, which is helpful. Probably on your own you may not have to answer that for yourself. When you get into a situation in your own like that, you might freeze up and not know, but art can help you process, and go, "Actually, no, I'd rather be confident in myself, and put everything on the line for somebody else." Maybe you're that kind of person, or maybe you're not. That's part of the question.

OK, number six, "We reject many experiences, people, places, and eras that have something important to offer because they come in the wrong wrapping, or leave us disconnected. It's a little hard one to unpack, but the idea that if you look at another era or another culture, and think, "That won't apply to me."

It does. Again, Hamlet in the middle of Papua New Guinea. We're all dealing with this same kind of same stuff, so what theatre, and story, and art can do is this amazing convergence of culture so that we all realize what human experience is, and that diversity, even though it might be unique to you, which makes it fascinating, pretty soon down the line you'll realize it actually not very different from you at all.

That's part of why we love stories about people that are different from us because again, it satisfies this. "Oh unique, that's not me. I'd like to learn, and the satisfaction of going, "Oh, they're just like me. Wow." Is that amazing?

The last thing is, "We are desensitized by familiarity." He goes a little further. "And live in a commercially dominated world that highlights glamour." The main point of number seven is it's a resensitization tool. Art peels away our shell, and saves us from our soiled, habitual disregard for what is around us."

Basically, I think what that means is it allows us to focus, lean in, examine something small, and seemingly perhaps either insignificant, or something, again, that doesn't apply to you directly, but of course, as you lean in, you see how extraordinary something is, how special something is, how moving the smallest thing can be. The smallest touch can be the ending of a play.

It can be the climax of a whole story because it means more than you think it means. If we're used to this sellable kind of world where oh, that intimacy is just for show, but then you see what intimacy isn't. If it actually is authentic and real, and that's this goal of theatre is a kind of authenticity combined with artistry.

All right. Thank you for letting me read those. I just find that so incredible and inspiring, and frankly a source of a lot of great moments that, if I look at my play going, "Why isn't this connecting?" I can go to some of those and go, "Oh, she's not hitting bottom. She's not hitting the bottom of her sorrow. We just have to walk her right up there, put her down, pour the worst on, and we're going to see what that happens."

I'll tell you, over, and over, and over again, plays of mine that have gone there, that have gone to that distance, usually about sorrow, I have more emails, more conversations, more people coming up and saying, "I had no idea that I felt this way," or, "Thank you for writing something that's my story." It's not their story, and it is, and it's not, and it is.

Again, thinking about all of these as ways to heighten and focus your story, will tap into the very essence of why we tell them at all, which isn't that exciting? That's the point, right? That's the point of all of this because it's not just entertainment. It's not just a passing of two hours time. It's certainly not money, why we do this.

It's because there is a universality, a commonality, the kind of grand, and yet absolutely minute perfection of humanity. It's a funny word to use perfect for it, but it is because even in all of the flaws, and all of the dirt, that's actually what we want to see to know that we're not alone in this, to give us a sense of OK, when it gets bad, I do think of King Lear.

Actually, there's a play that I'm doing, I haven't acted in a long time, but I've made myself do it for this play. It's kind of a one-person play, but it's about losing my father and my grandfather to Alzheimer's, and of course what did I do? I go read Lear because I don't know what's going on with him. He doesn't know me. I'm his oldest grand-. He doesn't know me. What do I do?

I go to Shakespeare. When I was in high school and dealing with boys, I was like, "What did Juliet do?" It's not the best road map for that. Over and over again we see, we can stand up and meet betrayal, and sorrow, and joy in the theatre, and it excites us, and it is this funny thing about art, why that ...

PART 1 OF 4 ENDS [00:28:04]

About art, that's why we make it up, because life is confusing and it has terrible timing. Art focuses our attention on a journey, so that a person who wants to change something gives it their best shot and at the end, this is the secret pattern, either they are changed or the world is changed because of them.

Sometimes they get both, sometimes the hero is changed and the community is changed around them. Sometimes they try to change, they almost get there, they don't make it but the world changes anyway. It's got to be one or the other. If they don't change and the world doesn't change, why did you tell us this story?

I think about that when I think about Romeo & Juliet or Hamlet or Lear or all of these things. If it is about corruption or civil war or madness and greed and madness laying waste to a community, none of the people in Hamlet, Romeo & Juliet or Lear make it to the end. Except for Horatio, good job Horatio. But the world is changed because of them, right? That's the end of Romeo & Juliet is everybody lays down their arms and is like "They didn't make it, but we're going to change."

That's that glimmer of hope, that glimmer that we have to have at the end. Oftentimes it feels cheesy, wrapped up, again this is kind of a structure question of when you get to the end, what is the end? When do you know it's the end? How much of the end is too much? When do you say curtain and let the audience go back to their real lives?

That's part of it, sometimes you can wrap things up too perfectly, there's always that "Well, that had a bow, a bell, and a cupcake on it." Sometimes there's those endings that will go "But what? That's it?" Don't you hate that feeling? I hate that feeling so much. Or just a little too soon, I needed a little bit more information to know that everything is going to be OK or that it's not going to be OK, either way. Those cliffhangers are fine for TV, but for theatre we need a little bit more like "And it's over."

That was our social anthropology evolutionary psychology lesson for today. It's really cool, if you are interested in the science there's a ton of stuff about this base cellular level as to why we might need story to learn the way we do, to connect the way we do, which I find pretty fascinating and makes our art form pretty extraordinary.

Who's the author of that book?

Alain De Botton and John Armstrong. I'll leave it around and it's gorgeous too, there's all these beautiful reproductions of paintings and things.

Are there any questions on that? I love to think about the epic nature of what we do, I think that makes it so much more valuable and interesting and the answer to those questions about some of us who've been in the class before have talked about those plays that you still think about, decades ago, you saw them or moments and usually it's moments in a play.

We'll talk about this idea of creating moments because that's really what sticks. We can't usually even contain a whole story in our recollection easily but man, I remember this one performance of Hamlet surprise, surprise, where poor Ophelia, instead of drowning, she is in a tub, I think I told you this. Oh my God, this memory is so vivid, Actor's Express, when I was fourteen in Atlanta, it's this wonderful company, Chris Coleman was running it at the time and they did this amazing production of Hamlet. It was my fifteenth or fourteenth birthday and I took all my friends to Hamlet that's the kind of friend I had, happy birthday Laura!

Ophelia was in this white tub, bathing and the scene was happening around her. She was divorced from it and at the end when she is supposed to drown, they start hoisting her up to the ceiling, dripping wet, wearing this white dress, what! Oh my God, right? That is unforgettable. I don't actually know if that's what happened, but in my mind, that's what happened. Something about that performance was that evocative.

I didn't even understand it that much when I ... I don't even understand all of it now, but there's something about it that was so beautiful and terrible, and grand and extreme, and unique, right? Check, check, check, check, check. Finding the preview of our discussion about moments is finding places for your story to have room for that kind of artistry to it, that's going to make it unforgettable.

I'm going to stop talking for a second, so if there's any questions or things you want to talk about. Yeah?

I'm thinking about myth and Joseph Campbell, the writing that he's done I think helps explain this as well in terms of many, many different people, a lot of his stories come around and around again-

Over and over. Yeah and actually there is this wonderful book, it's the one I was telling you about earlier, Into the Woods by John York. His last couple chapters are about this, his argument is that what Joseph Campbell actually discovered was not the mono-myth, but was story structure.

OK.

It's the reason why we tell stories a certain way, but again, that pattern is over and over again. We have someone who's sent out on a challenge, because something is wrong, they try to fix it, they fail several times in several ways in increasingly terrible degree and then they come home. Into the Woods he calls it that because it's really about somebody going into the woods, coming back out changed. That's a story. People and pattern, you go in and you come back out. Yes, exactly.

Thinking about that doesn't ... there's a danger of thinking about it as this "well-made play model" which we have that term because there was this French playwright, eighteen-something or other, that literally it was like four-hundred-something plays, where he had this "well-made play model" and he could have interns come and fill in different character names and fill in different traits and he would churn'em out, churn'em out, churn'em out, same thing kind of happened, someday this that, he has this moment, he has that moment, boom. There's this allergy to the sense of well-made play that's built on structure. Of course, that's the extreme silly version.

I think what a well-made play actually is, is a well-done story, a satisfying story. You can satisfy in a lot of ways, which is partly what we're going to talk about with the sense of structure. This is like all of the "why" we're about to get to the "how." I think knowing the "why" can start to answer for you, the "how."

You're going to need these things, you're going to need a person who wants something ... OK I'm just going to read to you, here's what a story is: "A story is a purposefully arranged," that's your job, "and conveyed" that's the theatre's job, "series of events" that's important, series of events. "Focusing on one character's choices and struggles and the people of influence around her, that culminates in a moment of meaningful decision for that main character, that defines her world and herself." I will say that again or?

Yes, please.

You're like "You're gonna have to or write it down or both." We'll kind of unpack that.

"A story is a purposefully arranged and conveyed series of events," that's important, series of events, "focusing on one character, the choices and struggles of that character," so "choices" is the word and "struggle" is the word. "And the people of influence around that main character, and the whole story culminates in a moment of meaningful decision, that that character has to make, that will redefine her world and herself." That's what a story is.

One more time.

"A story is a purposefully arranged and conveyed series of events, focusing on one character's choices and struggles, and the people of influence around her that culminates in moment of meaningful decision, that redefines her world and herself." It's not exactly high concept, but-

No, no that's alright, sorry.

So the idea being that we're going to design something that does this, that's what story structure is. It's the sense that we're gonna aim the ingredients, the pattern, we're gonna do this dynamically, so that we have all of these things checked off.

OK, before you go on, one more time, I didn't get the whole thing.

"A story is a purposefully arranged and conveyed series of events, focusing on one character's choices and struggles and the people of influence around her that culminate in a moment of meaningful decision, for the main character, that redefines her world and herself."

So let's unpack it. We have a series of events, that focus on one character, we need a hero. I used to talk about dramatic structure only in terms of the hero, I've recently discovered of course that's stupidly wrong, which is why I added the people of influence around them. Those people are critical. Again we are a highly social species, we don't do things by ourselves, so we are focusing on one character, it is about one person, it is Romeo's story more than it is Juliet's story but you can't really do it without Juliet and you can't do it without Tybalt, and you can do it without Mercutio, right?

We have all these people that are deeply important, but it is Romeo's choices and actions that we're watching. One character's choices, that's the huge word "choice, choice, choice" they have to make choices. They can make bad ones, they can make great ones, but it's all about the choices that they make.

Why? Because choice is a response to information and it precipitates action. Choices are the things you make once you've gathered some information, you may make a wrong one if you don't have all the information, right? When Romeo decides to ax himself, wrong information! Fake news! Bad choice. A choice generally prompts and action, you don't just say "I will be king," you have to go do it now.

It's the crux, the choice-making, the decision in one's mind that's the main thing you're influencing right? It's the characters that have to wrestle with their own mind. You know those people, I'm kind of like that about eating for dinner, "What do you want?" 'I don't know, something, I don't know, whatever." My husband's like "Would you tell me what you want? I'm just gonna list things, Mexican, pizza, sushi." I'm like "Yeah, sushi. Sushi's fine." That's still annoying and it doesn't do anything and it's not helpful, so that's why it's not fun for a character to be totally reactive to everyone else's choices. The main character, that's the hard part, making a decision is hard, that's why when it's dinner time and I'm low blood sugar, I don't make it, because it's too hard, I don't know, just put food in my mouth. You're learning a lot about me right now.

That's what's so critical, choice-making, again everything I'm about to say is a challenge for you to go "OK, when do they make that choice? How do I set it up so they have to make a choice? They can't go home and go "I don't know, choose for me." You have to find the caldron for this to happen, this alchemy, this chemical change in a person, that would give them a choice to respond and make. You have to find the choice to make.

The struggles, so backup, "a series of events focusing on one character's choices," which I probably should have put this in the other order, "choices and struggles." The struggles are gonna prompt the choices and those choices that you make will probably prompt more struggles, which will prompt more choice, right? That's the series of dominoes that we're playing with here.

The struggles element, is part of this pattern breaking. We usually start a story in a world where everything's fine, Harry Potter's life isn't great but it is what it is and then, he reaches this breaking point. What actually happened in Harry Potter? That's too complicated, let me switch.

We can go back to Hamlet we can always go back to Hamlet. Before the story begins, Hamlet's life is fine. His dad's King, it's all great, he's got a weird uncle but it's fine. OK, great. The struggle starts when Hamlet's dad dies, now he's this mopey prince, so that's bad, but then it gets worse. In the second scene, a ghost shows up and tells him not only is your dad dead, he was murdered, by that guy! And points to his uncle.

That's a struggle, now he's struggling, "Oh my God, my day, it wasn't just some happenstance, which is bad, death is already hard enough, now there was intention behind it, that makes me furious, rageful, and sorrowful all at once. And I know who did it." Which means now he's got a choice, what's he gonna do? We as the audience go "Oh, man, what would I do? I'd move. I'd move out of Gotham City, everything bad happens in Gotham City."

Now he has this choice, the struggle prompts the choice and then the choice to go after the king prompts more struggle, "How the hell do I do that? Now I'm caught, people seem to be dying all around me, now I'm struggling with killing my own self, to be to not to be." Boom, boom, boom. Struggle and choice, struggle and choice.

Next "And the people of influence around them." This is where your craft is gonna come up, who are their friends? Who are the people that seem like friends but aren't? Who are the people that tell it exactly how it is? That kind of friend that you're like "You look fat in those jeans." We need that person.

These people aren't just landscape, they are not just furniture in the story, of course they are part of the choice-making, the struggle, the person that holds them to the fire, it's the Horatio. You need a Horatio, you also need Polonius. You need Ophelia and all of her strangeness, although I would totally rewrite Ophelia, but that's just me. Maybe add a few more women in your play than Hamlet. Not to be critical.

That's really important to get that balance right. Again, all of this is to figure out the struggle and choice. The ultimate choice that Hamlet is going to make, the ultimate question of Hamlet is, is he going to kill ... is he going to avenge his father? Not kill the king, cause you could avenge your father without killing, but that's probably where were going.

All of this struggle and choice, there is going to be this meta question, which we'll get to in a moment. "The people of influence around her that culminates in a moment of meaningful decision for the main character." That "meaningful decision" of all the decisions, it's the one, and again decision is prompted by information and prompts an action.

The decision that we reach in the very climatic moment of Hamlet is; the information that happens right before is that Laertes is dying, right? Spoiler. And he says the king is to blame, which is the final proof that Hamlet's been waiting for, again remember this scene ... I should have had you read Hamlet instead of just recalling all this. The final moment where he is surrounded by all the hoi poll oi of Denmark society, it's a big public fight between the prince and Laertes, it's a big deal, everybody's eyes are watching them, it's American Idol, everybody's looking. Here Laertes says to the entire room "The King's to blame." And the King's right there, right? Now everyone knows the King is to blame, Hamlet was right, it's been proven, he is vindicated. That's the information that happens right as Hamlet decides "Yeah, I'm gonna kill him. I'm gonna kill him, hu-yah, follow my mother, poison cup." All hell breaks loose. So the action of course was "Hu-yah." The decision was, "I shall kill him finally."

That's the big moment and that answers the question that we started at the very beginning of the play, "Are you gonna avenge you dad, or not?" And he says at the end of that, when he learns about the ghost, "Curse and spite that ever I was born to set it right." That's the end of that scene, we prompt into this five acts of madness.

So that is the meaningful decision, again, what is that decision for your story? What is the crux? At three-fourths of the way through, five-eighths of the way through the play, after that intermission, if you have an intermission, if not there is a moment of chaos which we'll talk about these dueling moments of chaos.

You get to the end of the play, what is an end of the play? It is an answer to that question that we start at the beginning. It's not an answer to the philosophic question of the play, what is life? Blah, blah. What is loyalty? What is a duty? All this stuff. Those questions are never really answered, just continually asked over and over again.

The specific answer is going to happen at the end of the play and it needs to have a decision. If it's a love story, the person finally decides, "I'm gonna tell him I love him, I love you." It might be a la Casablanca "I love you, goodbye forever." I think that's so great. If you're in Miss Bennet it's "I love you, kiss everything's happy, yay!"

The last element, it's "a meaningful decision of the main character" that's what culminates, "that redefines her world and herself." In that moment of Hamlet that decision Hamlet is deciding to be a killer. He's been wrestling with this, he's deciding in that moment, the hero of our story is deciding "I would rather have this kind of vengeance, the be the kind of person that goes 'Good, I'm glad everybody knows that you're a killer. Done.' No, I'm not done, you have to die, you have to die by my hand." That's a different kind of decision than like "Yay, justice has been served!" No, he is, again Hamlet is kind of dying, as is everyone else, in the play at moment. That's a great moment, if Hamlet's dying, he's like "You're going with me brotha!" That's what I mean, this redefinition moment.

In Aristotelian terms there's this anagnorisis, wait that's the reversal, what's the revelation? There's a word for revelation and that's what happens at the end of a lot of Greek plays and part of what Aristotle defined as part of a good play is that you have to have a revelation at the very end. That's what this is, I think a decision is a revelation of who you really are and this is where those wonderful concepts that we kind of talked about, these grand concepts, these extremes, these moments of terror and beauty, they're going to culminate in this decision.

If you're a person it's like Sophie's Choice you have to make a choice, who are you in that moment? That decision is also going to redefine the world because if Hamlet hadn't have done that, maybe King Claudius would have lived and maybe the King of Norway wouldn't have taken over Denmark and the world ... There's lots of reverberation to those decisions, but it's your job to figure out what is that critical decision that is going to define that person? All decisions define us. Aristotle says "It's what you do, not what you say" which of course we all know instinctually, but oftentimes we write characters that say a lot but don't do anything. Doing is who you are, doing is what you mean.

That's the sentence version, the word problem version of dramatic structure.

I will also pause for a moment to talk about a little bit more of why art? And why it's so damn dangerous to people who want to control a society, why you try to sweep the artists away as quickly as you can if you're in some sort of authoritarian, because of emotional intelligence. That's what art offers us. It's not statistics, it's not science, it's not even a well-framed essay. Art is emotional and oftentimes emotionality is equated with some sort of chaotic nature, it's often too emotional that word floated around a lot when we're trying to make big political positions.

Emotion is bad. Emotion is unstable. In fact, emotion is what makes us human. Storytelling informs us of that and again in that question when we put a story together and we start to ask ourselves "What would I do?" It is an emotional response that often helps us define that, which is actually a good thing because emotions, even though it's a mix of chemistry in our bodies all the time, there is an emotional intelligence that gives us oftentimes closer to truth, gets us closer to truth than information.

Information as we now know, is easily manipulatable. History is easily manipulatable. The story of time, we can, with a few words, change what we seem to know.

Emotionally, if you see families ripped apart and the bread winner of a family is being dragged away into a country and leaving five little kids, you know that's not right. You don't need any statistic to go "Well, actually if you look at the economic..." Uh-uh, no. Wrong, that's totally wrong, because you ask yourself "What would I do?" I would be inconsolable, I wouldn't know how to go on. That's an emotional truth, that storytelling, that visual art, that music gives us. That kind of amazing mathematical mystery of how music imparts emotion to us, but we feel it, every time.

Story after story puts that to us as a way of practicing our emotional muscles, so that when we hit that in real life, we go "Yeah, I'm not going to be the person that allows that because I know through empathy, through this emotional intelligence." That's why art's dangerous, because you get to practice justice and equality and those dangerous things that are maybe really obvious when they're put in human form and taken away from policy or-

Courage.

Courage, yeah there you go. Courage, exactly.

What is the emotionally important moment of your play? If your play kind of sails along like "Yeah, things kind of come at them and they bounce off." That's actually not gonna be ... it can be a fine play, it could be a lovely evening's entertainment, but when is the point where the audience, grips their heart like that? Or if it's comedy they can kind of go "Oh no!" Usually comedy you have a lot of wincing, in those revelatory moments. Or of course, bursts of infectious laughter.

That's when you know you're hitting the right peaks. Again think of it as a song that kind of has three notes to it, it's gonna be fine, could be a lullaby or whatever, but if it's Beethoven we're going up, we're going down, we're slamming to a halt. That's again, in this pattern breaking way, what we want. If every scene has the same arc to it, it doesn't go very high or very low, again fine, could be fine, but you don't want to write a fine play. You want to write a play that's like "Wow, that was a rollercoaster." What's a good rollercoaster? You go really high, you do a bunch of frigging' flips, you feel like you're about to fall off, that's what's fun.

Thinking about that in terms of how you design your story.

Now we spend a lot of time on the why of theatre and art and story, now we're going to try to look at the how. Yes there is structure, engineering, architecture. I actually take great solace and inspiration thinking about it, in terms of something I can build, piece by piece. It takes some of the mysterious ominousness out of story-building and playwriting, which that feeling when you're at the blank page and the cursor is going like that and you don't know what to do next.

I like to have these elements, to have unpacked it, to have something to examine, to figure out. Maybe I can mix and match and find, discover a story, that satisfies. It's really not about goodness or badness, it's about satisfaction.

Satisfaction is different from person to person, what you're going to think "Ooh that was a great story," might be slightly different from a lot of people. As things in the human condition tend to be, we're actually a lot alike, about what we find, satisfying.

This is where we're gonna start diving in here. I'm going to start by throwing out a bunch of things that I have found, in a lot of reading, and experience, a story needs and I'll try to put them in an order and see if we can come up with a rough shape, that you can then apply and compare to the story you're hoping to tell or one that you're in the middle of. Maybe as a way of going "You can amp up the stakes here, add this element that your story doesn't quite have" and just those two things might redefine where you're going to get to something that will be satisfying to you and to an audience.

This is our line of time, obviously as the play goes on, opening of the curtain, close. I like to think of this as kind of the level of the stakes, the tension of the play, the emotional grip that a play has at any one moment in time.

It's usually and actor term or a director term, "raising the stakes," we kind of know what that means, the stakes of any decision have to be high. It's not just the stakes of "Do you have some gum or not?" Those stakes are fairly low, if you don't it's like "Alright." But if you have the antidote to this poison I'm currently suffering from, stakes are really high.

We really want to aim the story, so that the stakes get higher and higher and higher as we get towards that crucial moment of decision, self-definition, et cetera, et cetera.

Couple of things that a story needs: A hero-

PART 2 OF 4 ENDS [00:56:04]

Thing that a story needs a hero. We've talked about this, this is the person, it's funny how even that can be hard to define or hard to commit to. "Well, it's actually about this family more than just one person."

Oh, OK, but so part of the definition of a hero is whose action does the play follow? Who is taking steps, making decisions, who is the forward momentum of the play. And a hero can react to the world around them to antagonistic forces, etc. But it is there definitions that we're going forward. "I love this person, I'm going to try and show them. It was my dad who was murdered, I'm gonna do something about it."

Right so, hero we definitely need. A stasis, that's what happens before this catalytic moment at the beginning of the play to start the action or to start the necessity of decisions being made. So, the stasis is the world as normal and often times that can actually happen before the play even starts. That's the Hamlet we don't see. But some plays do start there, so we see this moment that disrupts the world. So, at least if you don't see the stasis in your play, you need to know when it is or was.

So, this is a big differential, the hero must have an internal crisis and the hero must have an external crisis. The internal being something that this character needs. What do they need it for? They need it for their own sanity, salvation, soul. It is something that they are struggling with. That they actually don't really even know what it is, much less how to solve it. This'll play out in a moment and I know it sounds a little odd, but I'd like to think that that's their need.

This is in contrast to their external crisis and external force, an external something that is pushing against them, something that they are fighting against. So, that's the want. The want is, "I need to fix this world, I need to fix this injustice, I need to fix the facts that I love that person, etc, etc. But these things are very different, the want they know. The want is obvious, the want is, "My dad was murdered and I know who did it. I want to punish that person. To find justice." This need, think of the need as a little bit more in that to be or not to be liminal space. "I'm incomplete, I don't actually know what completion looks like, I don't know what's wrong with me, but something is."

This is the Hamlet that at the beginning is moping around like a big old boar. Right, Hamlet's mom keeps being like, "What is wrong with you?" Something is, and that's before he knows what happens to his dad, right? So, there's something incomplete, a puzzle piece is missing and through the play he finds this completion. Again, that he doesn't actually have a name for, much less a solution for, but it's through this play, even though this is the dark version. So, at the end it is taking action. To be or not to be is all about, "I don't know what to do next," and at the end what does he do? "I know exactly what to do. You're gonna die by my hand."

And it's actually that sense of confidence and clarity of mission that Hamlet was missing the whole time or that he was kind of flirting with. "Oh, I'm gonna try to trick him into revealing, I'm gonna pretend I'm crazy," and all this thing when what it ended up needing to be done was him to go, "I know you did it, the world knows you did it, and now you're paying." Right, that's the Hamlet that is new to us until that very moment at the end. Even with the York business, right, he never just does anything. That's the joke about Hamlet.

So OK, so the want, very clear, obvious, external. And the need, mysterious, until through the actions of the play, this is the secret, the actions of the play will answer and solve this need in some way.

OK, another interesting element, a secret. Ideally a secret involving the hero, sometimes it is the hero's secret, sometimes the secret is external to the hero, but the hero will find out and that's part of the this moment and this moment. Secrets, secrets are our friends. This is the people of influence around the said hero, they're really kin or strangers. It's not necessarily friends or foes because kin and strangers could be either. The strangers could be the good samaritan that you know, that you don't know, but you need. And of course [inaudible 01:01:14] your kin, can be the worst of the worst. But it's really about this balance, I find. The people who know you well, that can either turn that into a bad thing or a good thing. And strangers who come into the hero's life as either, "Oh my gosh, Juliet you're Juliet, I don't know you, but now I love you," or, "I don't know you, but you're dangerous."

This is this pattern breaking element we were talking about, this uniqueness. All of that stuff is interesting. So, think about who in your play you would categorize as kin, it doesn't actually have to be a family member, but a close friend, a confidant, etc, and strangers. And this could actually be a person that used to be kin, but they have changed so much they are a stranger now, right? So, maybe he comes back after a long period of change or somebody because of- I don't know, so all kinds of mellow drama here. But, some psychic break that makes them different right?

So, that's a great element. Alright, this is the fun stuff that kind of happens, starts happening as we approach the half way point towards the end of the play. OK, I missed this one. Opposition, this is kind of in this element, in terms of the want and the need. Both want and need need an opposition that is equal to how much this person wants and needs them. I.e., an opposition is not a very good opposition if it's easily surmounted, right? So, there needs to be this equal and opposite pull internally to the character, what their need is, needs to be balanced by, "But it's too hard for me to deal with," or," I'm too scared of approaching that need in my mind." Right, the fear and the ambition need to be exactly equal.

And it's the same with the external want, right? Killing a sitting king is not super easy, if you are the prince, as our new prince, our dear Dane is. Right so, it has to be hard or else it's no fun. Telling someone you love can be the hardest thing in the world, as easy as it sounds in comparison to assassinating a king. Yeah OK, so equal and opposite, we should write that. Equal and opposite. That's just how we're going to make it believable, keep that engine going, keep the dominos falling, again if it's too easy the play's gonna be over in two minutes.

OK, so these are things that I've started to realize, at least my plays need. When I ask, "Why is this play done too quickly? It's only 50 pages long, what am I doing wrong?" Or, "It's just kinda flat, I don't care about the characters," right? You always hit that point, some plays where you're like, "I don't like them or care." Chaotic peaks, so these are these actual peaks, visual diagram to actually help you. Chaotic peaks, what I mean are moments in the play when things were going well or when questions were starting to be answered and suddenly they're not.

There is this element of chaos thrown in, they are often also down here, an emotional rupturing point. So, I will use, I was gonna use an [inaudible 01:04:23], that's a little weird to talk about when down play, but I'll do it anyway. Partly, because it's fairly easy structure as far as romantic stories tend to follow easily into to structures.

This is the act break, the peak of this moment. What is chaotic about it is there is a stranger that shows up right at the end of the act. Right as they are like, "Hey, I like you, do you like me? I think you might, OK this is going well, it's going good. Alright here we go," and oh my god, fiance enters. One of the people has a fiance, that upsets things. Suddenly the play might have ended right there, expect for this new element. This chaotic element that now throws everything and you notice that we're not back here after, we're not back all the way to where the stakes are low because now we care. Whatever happens, the audience and the characters, at this point, care and so the stakes are higher. Stakes are when you have to care, for the stakes to be high.

So, at this point it's usually right at halfway through the play. Even if there is no act break in your play, there's gonna be something right in the middle there that makes things all the more impossible, all the more complicated, all the more hard for your character to accomplish. Often because it adds a new complication, we were just getting a handle on the old complication and now there's something new to deal with. Like to think of them as chaotic peaks because often this is a chance to really write some amazing moments. Which we will, I'm gonna write that down so I remember to [inaudible 01:05:54] that.

Right, plays are just made of amazing moments and often times what helps is if I have the play, even if we're getting close to premiering the darn thing, I have to think, "What moment am I missing?" Is there a moment in this play that has a chaotic peak, that has an emotional rupture, that has a moment of offering or sacrifice that has a moral infliction point? Where someone usually, that's called the decision, but I wanted to break it down a little bit. Right, these are moments that you can put in your play if they're not there or you can design around them as you're building, but if they're not I'm telling you you're missing an opportunity to really go deep. These are the moments that are often the most fun/challenging for actors, right?

Think of what would be so amazing to perform. This chaotic peak when Mercutio dies. Right, that huge fight that gets out of hands and suddenly one of our favorite characters is dying in front of us, what?! Dying so beautifully[inaudible 01:06:59]. Right, that's an amazing moment and there's that joke in Shakespeare in Love, like, "I die, halfway through the play I die?" And then he's like, "It's a good death scene," towards the end, right? Cause it's great, that's unforgettable, that moment.

Does you play have a moment that has chaos? Something happens, it changes everything. Right, that's that moment, I think that would probably be right for Romeo and Juliet. That's right about halfway through, when Mercutio dies. What a moment, unforgettable, changes everything, right? Romeo is now not just like their families didn't like each other, yeah now somebody died and then of course Tybalt's dying, Mercutio's, everybody's dying. Right, suddenly we've taken what was already a complicated love story to an almost impossible, "No, no you can't be with her now, you can't! This is bloody again, bloody battles now," right?

OK so, challenging yourself. Where is that moment when all hell breaks loose? I like to think of it as the "Oh shit" moment, "Ah, shit!" So, in Our Dear Miss Bennet, not quite so bloody as Romeo and Juliet, and Hamlet. This is a moment that seems to redefine everything, that makes their love almost impossible, and it was actually a fabulous note by a wonderful director Sarah Rabosin. Margo and I were stuck about this play and was like, "It's good, but I don't know it doesn't feel like, huh what's wrong with it?" And Sarah, we gave Sarah it to read cause she's a great Austen fan and a fabulous director who's worked with both of us and it was her insight to go, what happens in Jane Austen there is a moment where their love is impossible. It's absolutely, you can't, you cannot do it. It's not just inconvenient, it's not just like, "Oh, that would be awkward." No, you can't, absolutely can't.

Usually involves someone else is married to whatever, this works in rondays too. "No you can't, he has a wife. Sorry, you can't, done." Right, but nothing is done in the [inaudible 01:08:50] we shall persevere and yet she persisted. So, at this moment that's what we realized we needed. We need to have that impossibility, that moment of like, "Oh, you're adorable, awkward, nerd love is fun to watch, but now we're gonna make it hard."

So, the second act, that's what's driving that second act. Is now we have to deal with this fiance that he didn't actually even know about, but accepts because it seems like it makes sense and she's like, "You had a fiance the whole time? Now I hate you." Awesome. So, now that's impossible on her side and impossible on his side, something, we get the fun of trying to untangle that. Trying to get to a point of the second chaotic peak. This moral inflection point, actually this peak is usually all of these at once. This one is probably like one or two.

But, this will be the climactic moment of the whole play and there's chaos, right? In our adorable Miss Bennet, it is a chaos of the families together, people are coming and going, he's leaving, she's trying to, there's a moral infliction point. Both he and she have to make a big decision that defines them both. Is she gonna be the person that lets the love of her life walk out the door and go, "Well, I just, I couldn't say it to him. I didn't want to, he should've known,"? No. No, she's gonna be the person that's like, "Hey! Hey, I like you, you don't have to marry her you should marry me."

Right, that's actually really hard to say, I can't imagine ever saying that in my life. Right, that's where you put your characters through the things that you can't imagine doing, right? But, that's what's fun. We all known that they like each other, it's not like a great mystery. At this point in the play we're like, "Somebody's gotta tell her, you gotta tell her, you gotta stop and tell her." There's always, that's what I love about Jane Austen it the whole like, "Kiss her! Kiss her! Kiss her! Kiss her! Kiss her!" My husband hates watching Jane Austen movies with me because I'm just like," Kiss! Kiss! Kiss! Kiss!"

But, that means that it's working, right? I'm invested, I care, I want that for them because I know what they want. Alright so, at that point she has to make this big decision of being honest and saying a thing that you're not supposed to say in [inaudible 01:10:51] England. You're supposed to be buttoned up and unemotional about it. And he has to make the bigger decision, which is to say, "No!," to his fiance, "I don't love you," that's a huge thing to say and to decide and to say. And to say, "I do love you and I'm gonna to the hard thing of moving forward," right? Again love stories make this quite easy cause the want is very obvious, we all know what it's like to be in lust or love or something.

But, again not just one moral infliction point, but two. Chaotic peak, there's all this going on, they have to literally stop him from walking out the door to have this interaction. It's not like everyone's sitting, waiting for these decisions to be made, you have to stop the world to do it. An emotional rupture, she has to put it all on the line and kind of go, "No, no, no! You're doing it wrong!" He has to as well, in his, this is a character that's a little Darcy-ish, so it's not quite an emotional rupture because they're all British, but you know. For British people it is an emotional rupture.

And the offering and sacrificing are there too. She is offering herself really, not just in a like, "Marry me," kind of chattel way, but offering the vulnerability of honesty. That's really what she's offering. "I'm gonna, this is a naked moment. So, I'm gonna be totally vulnerable for you right now and say what I actually think and feel." Which is one of the bigger things one can do, in one's life.

Yes. OK so, I we think about these two moment as really what your play is building towards and around. We have to have those to have a play and figuring out what's between these things, what sets them off so that we earn both of these moments, that's the real hard work. That's the engineering, but if you know that you have to have two chaotic peaks, two moments of where new information, it's all on the line, you have to have these emotional moments where the stakes are as high as they've been so far, right? We have to understand that that's what we’re building towards, then it makes it a little easier to build, right?

Yes. OK so, now I'm gonna actually back up and talk about step by step, we're gonna plot out a play. Alright, here we go. We'll use this marker, that's fine there's enough, ooh that's a good one.

So, again this is not going to fix exactly with what you're doing, nor does it need to, but the idea and the challenge is to ask yourself, "What of this does my play have naturally? Like man, I've got internal crisis and spades, these are messed up people. What I need is some external driver, some external [inaudible 01:13:39]. So right, you can kind of pick what's gonna help and I will say the goal of this is not to get every story to be the same, to sound the same, to end the same. It's just these elements are gonna make it juicy, rich, actable, dramatic, it's gonna keep it away for being like just a short story on stage. Gonna keep it a bit from having so much poeticism to it that we don't have any grounded emotion. Right, it can be so beautiful that it's not real or the other way around.So, greedy that like, "Where's the hope? Where's beauty?" Right.

So, we're gonna try and find what's gonna work for you, but especially if you see like, "I don't know if I have a secret, nobody has any secrets in my play." Maybe you should. Maybe you should take something that is super well known by all the characters and make it a secret and see what that does towards, throughout the journey. If we didn't know we were adopted. That's an obvious one, I use to always joke about that one to my sister, "You're adopted." She didn't like it.

OK. Alright so, here we go with the beginning. Something is wrong in the hero's world. This is kind of ish right there, so something is wrong in the hero's world. She needs something, it's a deep need. The hero doesn't know what she needs, but there is hope for a better world or a better life if she finds this out. So, this is the actual beginning of this dance between need and want. Towards the beginning.

So, a series of occurrences, starting with a catalysis that sets the hero's want into motion. This is, "We're gonna lose our house if we don't, whatever." This is Hamlet figuring out the information about who killed his dad and it was murder instead of natural death, etc. This is the big information that's gonna set this character's external [inaudible 01:15:44].

But, there is hope. Basically why bother with the journey if there's no hope? So, we have to have some sense of, "I can make this world better if I do this or myself better."

OK, a series of occurrences make the hero's want clear. This is where we get that information, again, a scene of two into Hamlet actually. What the hero actually wants, again he doesn't know what he needs yet, but he knows after hearing about the ghost and talking to the ghost what he wants. So, a series of occurrences make the hero's want clear, such that a goal emerges. With that goal, for Hamlet it's justice, a plan emerges or if you’re Hamlet like ten plans. A plan emerges, "I'm going to enact justice." Also this is probably, we're still in the first fourth of the play at this point.

A team emerges. Kin or stranger they will be a team. The hero's need is still unknown, but the ignorance that you have a need and what it is starts to thaw at this moment. So again, we're still in like this part of the play. Where we get our team, we have our goal, Hamlet has Horatio, Hamlet thinks he has Rosencrantz and Guildenstern and realizes, "You're not so much on my team, you're an [inaudible 01:17:06] but I can use you and later kill you." Spoiler.

OK so, yes. So, now we're gonna move into this next part. A series of actions and attempts that confirm the hero's desire start to take place. So, this is a different way of thinking about it. It's not like you are actively getting your goal, you're confirming, "Oh, I do want that." Right, that's part of what the goal is. Is, "Do I, oh god this is gonna be hard. Do I still want it?" Even if it's that hard do you want it? Even if it's this hard do you want it? How much do you want it?

So, you're gonna confirm that the hero does want this goal and how hard it is. Again, if the goal is super easy to get, it's gonna be a short play. So, we need to confirm the hero's desire and the goals difficulty. I.e. this is harder than the hero thought and that her personal cohort is not enough to accomplish it. Horatio is not going to be enough to deal with it, you're gonna have to now enlist poor Ophelia. Even though she doesn't know she's being enlisted. You're gonna have to tackle Gertrude, it's everybody, right? Now we have these actors coming in, he's gonna do the play to catch the conscious of the king, etc.

So, right. The hero's personal toolbox and their cohort aren't enough to accomplish it. Yeah.

Yeah, so is this, are you talking about the team or the-

Yeah.

Or was introduced prior to this or are these new people too?

No, I think it's the people that they have around them.

OK.

Yeah, at some point you're gonna realize, "I don't have enough." And our dear Miss Bennet, her sisters aren't enough. Her sisters are like, "No, you're great Mary, you're great," she's like, "Yeah thanks, I don't want to be in the attic like you wanna put me, I want to be my own person." Right, but her sisters don't understand that they're not enough for her. She has to define herself. For Hamlet, of course there's a lot of people that aren't enough for Hamlet.

OK so, ish here we have a chaotic peak and either right before, right after there are moments of giving up and moments of perseverance. And that's really what all these attempts are, for Hamlet, for everybody. The scenes, which actually kind of work like this, have peaks of their own, right? Every scene has its own peak, its own climatic moment of emotional release, decision, that's what a scene is is an effort at a decision. And a decision is reached so we can move on. So each one of these peaks would be that emotional decision. [inaudible 01:19:52] scenes your play has.

But, there are moments of giving up and moments of perseverance. After the play it worked, but it didn't work enough. We here the confession of the king, but he's praying so it didn't work. We have this, we have that, right? When do your characters give up? How do they pick themselves back up and move on so that the play doesn't end? Alright.

So here, in this very moment is a huge moment of change and chaos in the hero's world. For Miss Bennet, this new character comes on and disrupts everything. This is halfway through the story, things are upended, made harder, weirder and more urgent. This is that "Oh shit" moment. Which we shall be crude and just write down "Oh shit". This is a moment where Romeo could've turned back and have been like, "Dude Tybalt is gone, Tybalt and Mercutio. Look I can't. Mercutio's gone, I can't, I can't go on anymore." Right, but instead he's like, "Nope, don't give up." Sally forth, make further terrible decisions, that we will watch with glee.

But, the big moment is halfway through there's something really does change. Again, this is that moment where if this doesn't happen you get that second act lag. When you're like, "Why am I watching this again?" You've been at plays like that, right? Where you're just like, "What is the point? Why do I care any longer." That's when you have to throw in some other canon that blows things up and makes it harder, but also deeply more interesting.

OK so, now we're in the last second half of the play. So that was our "Oh shit" that propels us in this direction. With the obstacle doubled our hero reaches the end of her known strength. So, now even though she realized her cohort wasn't enough, now she realized she might not be enough. This is the second act kind of redoubling, putting yourself back together. OK, OK.

So, the limit of her known strength are reach and she must admit a vulnerability. The beginning of act two, we talked about this last time, there is a moment of, there's an emotional breaking point. This emotional rupture. Usually happens right here in response to this. In Miss Bennet she's just over it, she's kind of losing her mind with pettiness, and rage. She lashes out at her sister, she lashes out at the guy. She's like, "I don't want to talk to you, please."

And, another play of mine, The Book of Will, this moment is a really powerful moment of grief. Ans so, the first part of act two is this absolutely naked exploration of grief and in all that that is, am I. It's an odd thing to say, but my favorite part of grief because it resonates with me, a story about grief, is when somebody just yells at God, "How could you? How could you? What is wrong with you?" Right, don't you, I'm sure, in moments of grief and sorrow have that like, "What the hell?! Why would any good God do this?"

Right, that's beautiful for the stage too. Partly again, because we're all in it together. We all know what that's like, but this is what that space is. This "How could you? How could you?", this emotional rupture. If it's a love story you can direct that less at God and more towards the other person or, "Screw it, love is stupid. I hate love. Love has always hurt me, so I'm not going to love anymore."

Right that's kind of an insane thing to say and also a lot of us will go, "I've been there. I know what you mean." So, this is a part for that vulnerability, that nakedness, the kind of charge, you don't give a crap anymore, right?

And also knowing your limits, "I can't handle this! I can't handle it! I don't wanna go on, I can't." Miss Bennet says, "I can't go on, I will go on." Alright so, this emotional breaking point, right about here, about halfway through the second act we start getting that recharge again.

So.

PART 3 OF 4 ENDS [01:24:04]

... getting that recharge again. The character realizes she's not enough. She's at this emotional breaking point, but she must put the last of herself on the line to accomplish this goal. She must offer some sort of sacrifice. She must reveal her true self.

These things probably they know, but they don't want to do it. This is where our equal and opposite obstacle ... You know you're going to have to give it your all, but what does that mean? Would you die for this? Would you murder for it? Would you give everything you have in resources for it? Would you sacrifice your family for it? How much of yourself can you put on the line? Your dignity? There's a lot of things we can offer ourselves. You must reveal herself.

How does she reveal herself? Through a single choice. Now we're aiming right towards here. We're aiming right at that choice that they know they're going to have to make, but god, God help you if you have to do it. If you're in that position, that's going to be really hard or really uncomfortable if it's a love story.