Lost Worlds and “Pansexual Extravaganzas”

Rediscovering Weimar Operetta with Dr. Kevin Clarke

When we think of operetta, words like “edgy” and “sexy” rarely come to mind. Dr. Kevin Clarke is hoping to change that through his work with the Operetta Research Center, which focuses on studying and reevaluating works from the first half of the twentieth century. These had long been denigrated as “silver operetta,” as opposed to the supposed Golden Age of the late nineteenth century, when composers like Johann Strauss and Gilbert & Sullivan created some of the most famous examples of the genre. Weimar operetta was a vibrant expression of international culture and sexual liberation, incorporating new musical influences such as jazz and frequently showcasing the work of Jewish artists, which made it a particular target of the Nazi regime. After World War II, social conservatives sought to keep these operettas in obscurity, repelled by their freewheeling and tolerant-minded explorations of sexuality.

Now, these hidden gems of musical theatre are making a comeback, thanks to the efforts of scholars like Kevin and directors like Barrie Kosky. Kevin joined us to talk about the ongoing reevaluation of this long-neglected part of operetta history.

Links:

- Explore the Operetta Research Center’s site.

- Find out about recent revivals of Weimar operettas by directors such as Barrie Kosky in this Irish Times article.

- Learn about the Operetta Foundation, a private research institute focused on operetta, and read about the University of California, Santa Barbara’s recent acquisition of The Michael and Nan Miller Operetta Archive from the institute’s founders.

- German-language readers can trace the stories of artists who were persecuted by the Nazis via this project at the University of Hamburg.

You can hear many of the songs from Weimar operetta online, via YouTube and similar sites. The following is a supplemental listening/viewing list of some of the most interesting and important examples:

- Paul Lincke’s “Berliner Luft” from the operetta Frau Luna.

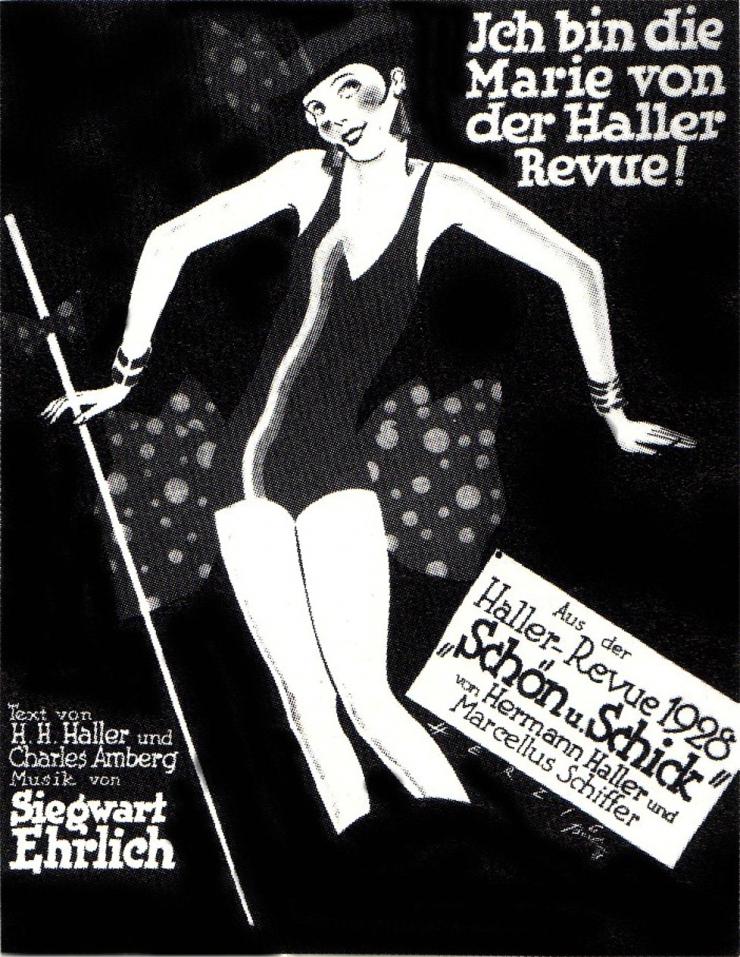

- The song “Ich bin die Marie von der Haller-Revue,” which celebrated one of the prime musical theatre attractions of 1920s Berlin; an image from the sheet music served as the inspiration for Liza Minnelli’s costume in Cabaret.

- You can see trailers for some of the recent revivals of Weimar operetta in Berlin, including:

- The Maxim Gorki Theater’s production of Alles Schwindel.

- The Komische Oper Berlin’s productions of Ball im Savoy and Die Perlen der Cleopatra.

- Fritzi Massary and Max Pallenberg sing “Josef, ach Josef,” 1928.

- Max Hansen in Im Weissen Rössl (The White Horse Inn), the most famous of the Weimar operettas.

- Siegfried Arno sings “Und als Herrgott Mai gemacht” from the same show.

- Two different versions of “Das Lila Lied” (“The Lavender Song,” music by Mischa Spoliansky and lyrics by Kurt Schwabach), the most prominent LGBT anthem of the era:

- Marek Weber’s 1921 version.

- Ute Lemper sings an English-language version.

Operetta star Richard Tauber sings Franz Lehar’s “O Mädchen, mein Mädchen” and “Dein ist mein ganzes Herz.”

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

Transcript:

Michael Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. It’s available on iTunes, Google Play, and howlround.com.

Hi, and welcome to the Theatre History Podcast, I’m Mike Lueger. If you’re like me, you probably don’t know much about musical theatre in Weimar, Germany outside of the usual suspects like The Threepenny Opera. But there was a flourishing world of musical performance during this era. Particularly in operetta. It’s a legacy that’s been all but forgotten because of the intervening traumas of totalitarianism, persecution and war.

Luckily, the Operetta Research Center in Berlin has been shining a light on the forgotten gems of the Weimar era, and in the process finding some unexpected resonances with our own time. Dr. Kevin Clarke is a musicologist and the Center’s founder. He’s also been involved in efforts to revive works from the Weimar era and bring them to a twenty-first century audience.

Kevin, thank you so much for joining us.

Kevin Clarke: Thank you for having me.

Michael: Your work with the Center focuses in particular on Silver operetta. What does that term mean, and when were the works that it refers to performed?

Kevin: The terminology of Silver operetta as opposed to Golden operetta is a comparatively new invention, new meaning it’s from the 1930s and ’40s. It generally refers to works of the time after The Merry Widow. So The Merry Widow premiered in 1905 and anything that comes after that would be today referred to as Silver operetta, including the 1920s with all its syncopated jazz operettas, Charleston operettas. And what it means today is an opposition to the Golden Era of Vienna Waltz operettas, so anything by Johann Strauss, Franz von Suppé, Millöcker. All these things that premiered in Vienna in the 1870s, ‘80s, and ‘90s and before The Merry Widow would be called Golden operetta today.

The term is deeply problematic because it sort of suggests that Golden operetta is worth more than Silver operetta, and if you continue this terminology, it will then get to lesser METALS describing the later stages of operetta. It was actually was not used at the time of the creation of these operettas, so if you look at an operetta guide from 1931, this terminology doesn’t appear. Instead you have a description of Offenbach operettas from the 1850s as opera from the spirit of parody. Then you have the so-called Vienna Waltz operetta as romantic Vienna Waltz operettas. Then you have the syncopated modern operettas describing the 1920s.

So this whole Gold and Silver is later and I would say it’s from the Nazi time because the Nazis were pretty much in favor of labeling the Viennese operetta as the original operetta, lending out the Parisian Jewish operetta by Offenbach and claiming that that Golden operetta is like the highest level of operetta you can get to. And Johann Strauss being like the cherry on the cake. And they said that anything that comes after the Silver operetta is a continuing degeneration leading to the Jewish-Bolshevist and Entartete Musik phenomenas that you have from the 1920s.

Michael: That’s interesting to hear how that term came about as a result of the rise of the Nazis, the political situation. Because as you mentioned, there’s all these new elements to the operettas from the time period that we’re talking about. You mentioned jazz, syncopation. I’m curious, what were the operettas from this time period like in terms of music, story, style?

Kevin: One thing you should always keep in mind is that operetta was commercial theatre from the very beginning that it starts in the 1850s. And it starts in Paris and spreads out very quickly via Vienna, Berlin, London, New York, Australia, New Zealand. It always used popular music of the time and preferably scandalous music from the time. So when you get to Paris and Offenbach, it’s the can-can as the latest dance invention. And when you come to Vienna a little later, it’s the Vienna Waltz and the polkas.

When you then come to the 1900s or 1910s, it’s the new things that come from America in this case, the cake walk, early forms of syncopated rhythm. Once the First World War is over, of course for the Europeans, that’s a major break in its culture because the old system is collapsing or has collapsed and people wanted to express how modern they were, how in tuned they were with the modern times, so they embraced everything that comes from America and that is syncopated music and what was then considered jazz. So it starts with shimmy music with fox-trots. It goes on to Charlestons later on and black walks.

And operetta at the time still being commercial theatre of course used all of these dance forms and if we’re talking about Berlin and also Vienna style operetta, they mix this kind of modern American influence music with the traditional European styles. This is what infuriated the Nazis so much. That’s what the degeneration was, that you mixed different racial elements. They wanted to keep it pure. And that’s why they then went on a really big vendetta to clean up operetta history and bring it back to what they considered was the original goal.

When you ask what the pieces performed were, it’s a bit like going to the cinema today. You had a very rich scene of commercial theatres and they played anything that audiences were willing to pay for. Today you could go to a cinema and you can have a Hollywood blockbuster, you can have an art house film, you can have a queer cinema film, you can have a tiny low budget film, you can have total nostalgia, you can have a romance movie. So basically all of that translates directly to what you have in the 1920s.

For example, in Berlin, as one of the major centers of operetta, you have totally old fashioned pieces for those who didn’t like the modern times and who were longing back to how it was before. You have the ultra-modern big pieces, you have the small scale cabaret operettas of which The Threepenny Opera was one. You have the film operettas made in Germany at the time that were very successful internationally like The Congress Dances and the Die Drei von der Tankstelle.

So it’s a mix of all of these things and interestingly enough, most of the successful composers and performers at the time really moved from one sort of area to another in this field. It’s a bit like on Broadway, the people were in vaudeville and they were in operetta and they were in early musical comedies and they were in early sound movies, because they were very versatile and they were doing anything that audiences would pay to see them for. And it’s the same thing in Berlin, or in Vienna, or in London, or in Paris.

Michael: A recent article in The Irish Times described some of these works as quote "pansexual extravaganzas." And I think that description might be a little surprising for those of us that don’t think of operetta as being especially risqué. What was in these pieces and how did their content reflect the broader culture and the time period?

Kevin: Okay. Let me put this answer in two parts. Most Americans when they think of Operetta will probably think of a book like Richard Traubner’s Operetta: A Theatrical History. That paints a very nostalgic image of operetta as ball gowns, chandeliers, the men in uniforms, drinking champagne. That is the image that in America was attached to operetta from the 1930s, ‘40s, ‘50s onwards. It has absolutely nothing to do with what operetta originally was and why it was such a worldwide sensation.

When operetta started in the 1850s in Paris with Offenbach, the main reason for its success was that it was considered totally immoral. It had nude women on the stage and I mean literally nude. You can read about it in Émile Zola’s novel Nana. It was basically theatre as a form of brothel, you went there to pick up women. So it was a genre that allowed for great sexual liberty on stage and off stage, and that was why hoards of men ran to see the shows that were put on and it’s the reason why people, moral guardians, including in the United States, got very upset about it and tried to sort of get rid of operetta as quickly as possible, but they weren’t successful.

So, that’s how it started. Once the success of operetta broadened and the audience widened, you get more middle class audiences coming to it who did not have such a liberal idea about what to do as the original high class male audience in Paris, and so the sexual liberty is very much toned down. When you get to the time of after World War I and this total renovation renewal of moral renewal also in Europe, namely in Vienna and in Berlin. This renewal goes parallel with the first sexual revolution. So you have, it’s a time of enormous sexual liberty and that is reflected in nearly everything. In the song lyrics at the time for popular music, they are all highly risqué. You know, really way beyond what Cole Porter did and I mean, it seems tames by comparison. It’s really very, very explicit. And of course, the people who wrote these popular songs are the same people very often who wrote operettas or what you would probably call musical comedy.

So many of these modern operettas at the time were about stories of young flappers not wanting to marry the man they’re supposed to marry and instead going on a world tour and having adventures and doing things that young modern girls were supposed to do. And they would use music that reflected that, so that’s why you get all these Charleston operettas and syncopated fox-trot operettas. And the pieces that were created in the Weimar Republic very much reflect that on some level or other. Sometimes it was really in your face nudity, dancing girls, dancing boys also, that was very much something that Berlin had at the time. Homosexuality being presented under the disguise of something else. But also when you get to the more nostalgic pieces that also were very successful at the time, let’s say like something like Blossom Time. There’s always an element of the risqué of the sort of the kinky in there. It’s never completely far away, it’s never completely gone from these pieces.

So if we’re talking about these Weimar era things that are now being rediscovered, you are talking about a theatre history or a theatre scene that’s very much like what you see in Cabaret, the movie. You know the Liza Minnelli, Joel Grey, all these little money, money, money scenes and two ladies and so forth. I mean, that’s exactly what you would see in these cabaret venues in Berlin where they would perform cabaret operettas. For example, like Mischa Spolianksky’s Alles Schwindel, everything’s a swindle, which is what the reviewer in The Irish Times refers to when he wrote his article.

These are very pansexual pieces because everybody is sort of potentially having sex with everyone. You should not forget that homosexuality at the time was still criminalized in Germany, so you couldn’t actually bring homosexuality onto the stage by naming it as homosexuality and by sort of showing it as such. So it was always veiled in something else. It was either about the ancient Greek doing things or it was about Nan’s characters or it was about good girlfriends.

Marlene Dietrich sang a famous song, "Wenn die beste Freundin, Mit der besten Freundin". She did that with her lesbian friend Claire Waldoff in a 1920s review in a big theatre. Everybody could have sort of understand what it was about, but it wasn’t actually said in words. So that’s the pansexual thing. You play with all of these things, you use all these codes. Certain kinds of nudity, certain kinds of Greek references or Parisian references, and people in the know knew what was meant and people who didn’t want to know could just pretend that they didn’t hear it.

And that’s the pansexuality. And Berlin operetta at the time was really very good at playing with all of these sexual levels in a very risqué way. So there’s always a punch line in all of these songs with a sexual joke, or a political joke, or both together. And that’s what makes these songs from the time so really great. In a way that American songs, popular songs, Gershwin, Jerome Kern and so forth, do not have. By comparison, they’re really, really like kindergarten tame.

Michael: Now who were some of the major figures in operetta at this time? You’ve mentioned a few names but I’m sort of curious, who are some of the big ones that people might want to look up?

Kevin: If we’re talking about the grand scale productions, probably one of the most famous ones is Erik Charell. He was a gay Jewish theatre producer and he ran the Großes Schauspielhaus, which was the biggest theatre in Berlin with 6,000 seats that he had to fill every night. He started doing pure reviews, then he got a bit bored with that after three years. And then he started updating classic operettas like The Mikado, so he made a jazz Mikado, he made a jazz Merry Widow right after Erich von Stroheim did the Hollywood jazz version of The Merry Widow in 1925. So 1926 you had Erik Charell’s version.

And then in 1927, he turns to creating new works and they are historic settings, so like The Three Musketeers, Casanova, and then The White Horse Inn. But he tells these historic stories by mixing classic music from opera, from symphonies and so forth, with brand new syncopated songs. So in The White Horse Inn, which is the most famous of this group, he has the Tyrolean dancers doing their slap dancing number and the next minute you have someone coming on and doing a fox-trot on stage in the Alps. So that’s how he used [inaudible 00:14:50]. It’s a bit like a Baz Luhrmann movie. So everything’s jammed into there and then mixed up and then spit out in a recycled way. That was the most successful single theatre producer at the time and The White Horse Inn is the most famous single show that came out of this particular tradition.

At the same time, you have Franz Lehár, the composer of The Merry Widow, writing his tragic operettas for Richard Tauber in Berlin. So it’s a bit like Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera but eighty years earlier. Lehár Tauber start in The Land of Smiles, in Friederike and Paganini. These were big opera pieces where Richard Tauber was the star and everything was sort of totally tailor made for him. So, that’s the other big one.

Then you have these smaller scale cabaret operettas, The Threepenny Opera is the most famous one of those but it was just one of very many. Mischa Spoliansky wrote a lot of those as well. Friedrich Hollaender, who later became very famous as a Hollywood composer writing for Marlene Dietrich among others, was one of them.

Then you have the film operators, the early ones, mostly composed by Werner Richard Heymann. He became very famous later in Hollywood, too. He had many Oscar nominations, for example, for Ninotchka, the Greta Garbo movie, he started out as the Music Director for the Ufa, which was the big production company in Berlin. And they made one big movie after the other. So those are sort of the big ones, and all the stars, all the composers, all the producers basically, they circled from one of these genres to the other and basically dipped their toe into all of them.

Michael: Now what happens to operetta in the 1930s as the Nazis gain power? And then later in the aftermath of World War II?

Kevin: In late 1932, you reach the absolute height of jazz operetta with pieces by Paul Abraham who is like, I would say, the greatest of all German language jazz composers, even though he’s Hungarian by origin. His last show in Berlin is the Ball im Savoy, which premiers in December 1932. And then in January 1933, the Nazis come to power, as you probably know. And they immediately set out to change that whole system.

The change means that they labeled this mixing of jazz and German National music, or what they considered German like Vienna Waltz also, this mixing was what they wanted to get rid of and they wanted to get rid of all of these popular 1920s shows which were written nearly exclusively by Jewish composers, Jewish lyricists, produced by Jewish producers, with a big Jewish audience. So, that all had to go. And their ideal was to go back to the Vienna Waltz operettas from the 1880s, but because at least the composers in that case were Christian. Nevermind that the lyricists were all Jewish, too.

So they started a campaign that basically eliminated these newer works from the 1920s and got rid of them. The way they got rid of them was a very simple trick, really, because they changed the theatre system in Germany. As I said before that, you have a commercial theatre system where anything that sells a ticket would be put on. After 1933, you have a subsidized theatre system and the subsidy of course means you only get the money if the politicians give you the money. So suddenly, the theatre directors are not playing shows because they attract an audience with it, but because Joseph Goebbels in this case as the propaganda minister approves of their choice of pieces and gives them money.

So suddenly everything becomes political and the whole system changes. Very sadly, after 1945, German theatre did not go back to the commercial system but it stayed a subsidized system to this very day. The subsidy system meant that suddenly all these old and nearly forgotten pieces by Johann Strauss, by Millöcker, by Suppé, were suddenly brought back and they were brought back with opera singers because the Nazis claimed that would enoble them somehow. And that’s what you get to hear on all of those old radio broadcasts and many of these old recordings.

At the same time, the audience of course didn’t want to just hear old, I’m not saying old-fart pieces, but let’s say old-fashioned pieces from the 1880s. They were used to modern shows. And so the Nazis brought in a whole new generation of composers, basically second rate composers, to write things in the style of the 1920s. But these composers were not Jewish and they weren’t as radical in their use of jazz and elements and syncopated elements.

So suddenly instead of, let’s say, Mischa Spoliansky, Kurt Weill, Paul Abraham, you get composers like Peter Kreuder, Fred Raymond, and so forth. And it sort of all sounds swingy and nice and from an American perspective, you probably think you’re in 1930s, 1940s Hollywood movie but it’s never as good and it’s never as original as the older composer generation was.

So in the 1930s, ‘40s, you get a whole series of film operators and also stage review operators that continue that Weimar tradition without being as sexually explicit but without being completely tame either. And what happens then is that after World War II, the big change happens. There is a famous historian, she’s called Dagmar Herzog. She teaches at New York University. She wrote a book about the sexual politics of the twentieth century in Germany, and she claims that the first sexual revolution of the ‘20s basically continues in Nazi times because the Nazis were really propagating a very liberal attitude towards sexuality. If you were one of the right Aryans, so if you weren’t one of the persecuted groups and if you were one of the people that they considered worthy of staying in Germany, you could have as much sex with whoever you wanted and enjoy it, and a lot of people did.

Obviously, after 1945 when the guilt question arose and people said, "What did you do when all of these Jewish people and all of the other people were taken to concentration camps?" Germans didn’t want to say, "Oh, we were having a fabulous time fucking around." Instead they said, "Oh, God. We were completely in repression," and so this whole sexual side was blended out and when the new German states were founded in 1946, the Christian churches, the Catholic and Protestant churches said, "Listen, after this moral disaster of the Nazis, you need a guiding light. We are going to be that guiding light and you should live according to our Christian ideals."

So exactly what the Nazis didn’t do happens after 1949, which is why in the 1950s and ‘60s in Germany, you live in a very sexually repressed era. And the operettas that were put on really reflect that. They take the sex that was already taken out a bit by the Nazis to the extreme and completely desexualize operetta. And of course, audiences in the ‘50s and ‘60s in that climate did not want to hear syncopated jazz operettas from the 1920s with pansexual things happening on stage, so that’s basically why these shows were really forgotten for a very, very long time. And it’s only in the last, I would say, ten years, for the first time ever, that this restricted sexual political climate is overcome finally. And we’re going back, we’re trying to reconnect. Younger audiences in Germany are trying to reconnect with that Weimar era buzz and suddenly discover how much fun Germans were able to have on stage back then. And you sort of wonder why it took so long to get back there.

Michael: As you just mentioned there, there are these efforts now to revive these works. And I’m wondering, what can you tell us about the recent revivals and how they’ve been received?

Kevin: I think there’s a new audience, that’s for sure. And the new audience that didn’t grow up in the ‘50s and ‘60s, in that climate of sexual repression, they really want their lifestyle reflected when they go to the theatre, when they go to the movies, when they watch TV shows. So they want sex, they want fun, they want something that arouses their interest in some way.

When I grew up, I was born in 1967 in Berlin. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, it was definitely not cool to be proud of being German. You wouldn’t run around waiving a flag because it always meant you were some kind of neo-Nazi and sort of reviving the worst parts of German history. Then in 2006, we had the Football World Championship in Germany and a lot of people suddenly discovered that Germany is actually quite a cool place. Germans have a sense of humor, they can be attractive, they know how to party, and Berlin is a super cool city. And suddenly the Germans themselves thought, "Oh, yeah. You know, if the whole world sees us like that, maybe it’s true. Maybe we are cool and maybe it’s not all gray and dark and guilt ridden as we were always told. Maybe there is something other than the classics, other than Goethe, Beethoven, and Wagner out there."

And suddenly they see that in the Weimar era, there was this buzzing entertainment industry right here under our noses and they produce all of these fabulous shows, apart from The Threepenny Opera. And these pansexual syncopated shows from the ‘20s are really quite close to what the new Berlin feeling is all about. And it’s certainly no coincidence that you have a TV series like Berlin Babylon now, exactly trying to revive that Berlin feeling from the 1920s. And that films like Cabaret are so popular again, and that people sort of think, "Wow! We want to get back to that sexual liberty that was there. To this musical liberty, to the originality of what was being created." How these international influences that came from the US were mixed with the German culture and then sort of come out again as something uniquely unique in a way. Something that only the Germans produced at the time.

And I think that’s why this new audience says, "We don’t want to hear The Merry Widow for the tenth thousandth time and we don’t want to hear the Fledermaus," you know, The Bat by Johann Strauss, "again, and again, and again. We want to discover something new. Something that we can relate to." And Barrie Kosky, the Australian director who works at the Komische Oper, was the first one to really do that. He brought back Paul Abraham’s Ball im Savoy, that’s the piece from December 1932, sort of the pinnacle of the jazz operettas from Berlin. And he landed a major smash hit with that. You can see the trailer on YouTube and it gives you a pretty good idea of what it’s all about.

And he didn’t just revive that jazz sound, he used a different kind of cast. So instead of you having your traditional opera singers standing there with a champagne glass in their hands and sort of waltzing around with a ball gown, he put big film stars and musical comedy stars onto that stage and they don’t sing with opera voices, they sing with their, what you would call musical comedy voices. I mean, for Americans, that’s probably the most common thing in the world. You know, Glenn Close stars in Sunset Boulevard or other people like that. That’s no big deal. In Germany, it was not done because the critics always said, "Yeah, but this music needs to be sung properly, otherwise you’re not doing it justice."

So Barrie Kosky said, "Fuck all of that." Pardon my language. "I’m just going to put a big actress like that Dagmar Manzel on there and she really rocks the stage. And he has [inaudible 00:26:33] there and some other people as well, and he put a half nude boy dance group on there, also half nude girls so it’s equally distributed. But it’s very gay. And he really emphasizes that sort of kinky pansexual 1920s aesthetic and it was a major success, and he repeated it after that with two Oscar Straus operettas. One was Eine Frau, die weiß, was sie will, which he staged with two people. Very minimalistic, very cabaret style. The two people, a man and a woman, they play thirty-three roles, sometimes at the same time. It’s really hilarious. And it’s always sold out. And then he brought back Die Perlen der Cleopatra, which is The Pearls of Cleopatra, an early 1920s jazz show that’s again with nude dancers in Egyptian costumes. And Dagmar Manzel the big star at the Komische Oper as Cleopatra. And that really is a sensation. It’s always sold out. You can’t get tickets for months and months.

And that really sparked interest in that repertoire because of course other theatres said, "Okay, if Barrie Kosky can sort of make big money by having 100% attendance, you know, selling out all these shows. Maybe we should try doing something like this, too." So after Barrie Kosky sort of pointed the way, a theatre like the Gorki theatre followed that lead. The Gorki theatre is post-migrant, very political, very young theatre here in Berlin. A very small theatre, too. And they dug up one of those cabaret operettas by Mischa Spoliansky, it’s called Alles Schwindel and it’s about dating. So everybody dates everyone, and like in dating apps today, they all pretend to be somebody else and get into a lot of trouble as the show goes along.

It’s extremely contemporary from today’s perspective and it’s very funny, it’s very witty, and the songs are very much in that jazz cabaret style. And the Gorki theatre used young stage actors, young film actors, who were just nominated for big prizes, and so they reach a new audience. And when you go to the Gorki and to one of those sold out shows, you see young people who would normally never go to opera, they would never go to a Richard Traubner kind of ball gowns operetta, but they can relate to this kind of operetta. So again, you’re reaching to new audiences.

And the third big one here in Berlin is the Tipi [inaudible 00:29:00]. It’s a tent where you can sit down and have dinner, and you sit at a table and you see a show, a big show in front of you. And they were doing Frau Luna, which is the original Berlin operetta from 1899 so it’s basically before all of these jazz shows, but they’re reviving it in a very glitzy, very show kind of style, very 1920s style. And again, you’re reaching another audience. It’s very touristy. Lots of Berlin tourists, Americans included, who come here and they want to see real Berlin, they go to this because it’s a Berlin show, it plays in Berlin and on the moon.

And so you have these three different groups. One is a total commercial theatre, the other two are state subsidized theatres. And one’s a big opera house with big orchestra, big chorus, big dance group. And the other one, the Gorki, is a small political theatre. And they all present sort of the same basic idea but they sort of represent different aspects of that 1920s Weimar Republic repertoire.

Michael: Now, you’ve given us a sense I think of what these operettas might have to offer us now in the twenty-first century. But I’m curious, what have you come to learn from your work with them?

Kevin: I’ve come to learn that, especially sexual liberation, is not something that just happened in the 1970s. So I personally, I’m a gay man, and when I grew up I was always told Stonewall is the beginning of everything. So 1969 and then onwards and it all happened sort of in New York and San Francisco. No, actually, the first sexual revolution happened here in Berlin, in my birthplace. I was wildly fascinated by this.

I always liked musical comedies and sort of the 1930s films also, Fred Astaire and so forth. And I was amazed that the 1920s shows that were produced here in Berlin sound so similar. When you listen to these old recordings, which are mostly on YouTube now, you would think you’re listening to a very good dance band, Paul Whiteman and so forth, recording from the United States. And that was the sound that was cultivated here in Berlin, only that the Berlin texts are actually better, the German texts are actually better. They’re kinkier, they’re wittier, they have more Jewish humor in them, and I thought, "Wow. Why is all of that forgotten? I mean, why did I never hear about it? And why are all these recordings there? On, you know, all the old [inaudible 00:31:26] discs. Why doesn’t no one take those as a role model when they put on operettas or any kind of other shows?"

So for me personally, it was a huge discovery to see what a vibrant, what a rich scene this was here in Berlin. And also to see how internationally connected it was. So if you’re talking about Berlin musical entertainment from the 1920s, these shows went directly from Berlin to Broadway. The White Horse Inn, for example, it went from Berlin to Vienna to Paris to London to New York. There were talks about a Hollywood version at the time, and the big Broadway shows by Romberg, by Friml, by Vincent Youmans they all came to Berlin and to Vienna.

So it was a two-way street. It was a very transatlantic intense business that was going on and sadly, the Nazis really interrupted this interaction between these different centers of musical entertainment and I think it’s high time to rediscover it. And the fact that young audiences in Berlin who go to the Gorki, to the Komische Oper, to the Tipi [inaudible 00:32:30], are a very mixed international audience and that they really enjoy that 1920s Weimar Republic repertoire again really shows that we are trying to reconnect to that old era again.

And for me personally as someone who’s grown up in Berlin in the 1970s and ‘80s when Berlin was a very gray place, a divided city with a wall, where you had to go through the Easts of the Russian zone to arrive in the Western civilization again. As someone who’s lived through all of that, it really gives me enormous pleasure to see a reconnection with a time when Berlin was really glorious, when it was in that pre-fascist era that you read about in the Isherwood novels, that you see in the Liza Minnelli movie, that you see in all those old photographs. It’s not just Kurt Weill and Brecht and The Threepenny Opera and The Comedian Harmonists, it was the whole city was like that. And it was so liberated.

I mean, the whole sexual revolution in terms of LGBT and queer revolution, it all happened and started here in Berlin with Magnus Hirschfeld and all the others, the Institute for Sexual Science. Today you see this in TV shows like Transparent, where I think in the second or in the third season, there’s a lot of Hirschfeld and that Institute. I mean, that’s all here in Berlin and Hirschfeld went to these shows, and these gay and lesbian stars that are connected with Hirschfeld were all in those operettas and reviews.

And I find it really fascinating to see what a glorious entertainment industry that was and it’s really way beyond of what happened in Oh Calcutta and all those gay and lesbian musicals that we praise now on Broadway. We all had that here in Berlin in the 1920s up until 1932. And so for me personally, it’s a great joy to discover all of that and to see that a new audience is actually enjoying the rediscovery as well. Because it’s part of my own history and I think it’s always great to see that your own history is not just your history, but you’re part of a larger history and you can connect with others.

Michael: We’ll post a link to the Operetta Research Center’s website, where you can learn more about the project and find a wealth of information about these delightful works of musical theatre.

Kevin, thank you so much for telling us about the fascinating lost world of Weimar operetta.

Kevin: It was my pleasure.

Michael: If you’d like to continue today’s conversation, please visit howlround.com and follow HowlRound and @theaterhistory on Twitter and Facebook. You can also visit our website at theatrehistorypodcast.net where you can find links to all of our episodes and you can email your questions and comments about the show to theatrehistory@theatrehistorypodcast.net.

A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound who make this show possible. Our intro music this week is "Ich Bin Die Marie Von Der Haller-Revue", and our outro music is "Josef Ach Josef" sung by Fritzi Massary and Max Pallenberg. You can find links to recordings of those songs, as well as many others from the Weimar era, in the show notes for this episode.

Thanks as well to Tip Cress who designed our logo. And finally, thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here