Ann James: Hi, Kaja Dunn! How are you, illustrious Broadway-credited intimacy director/coordinator? Congratulations for that!

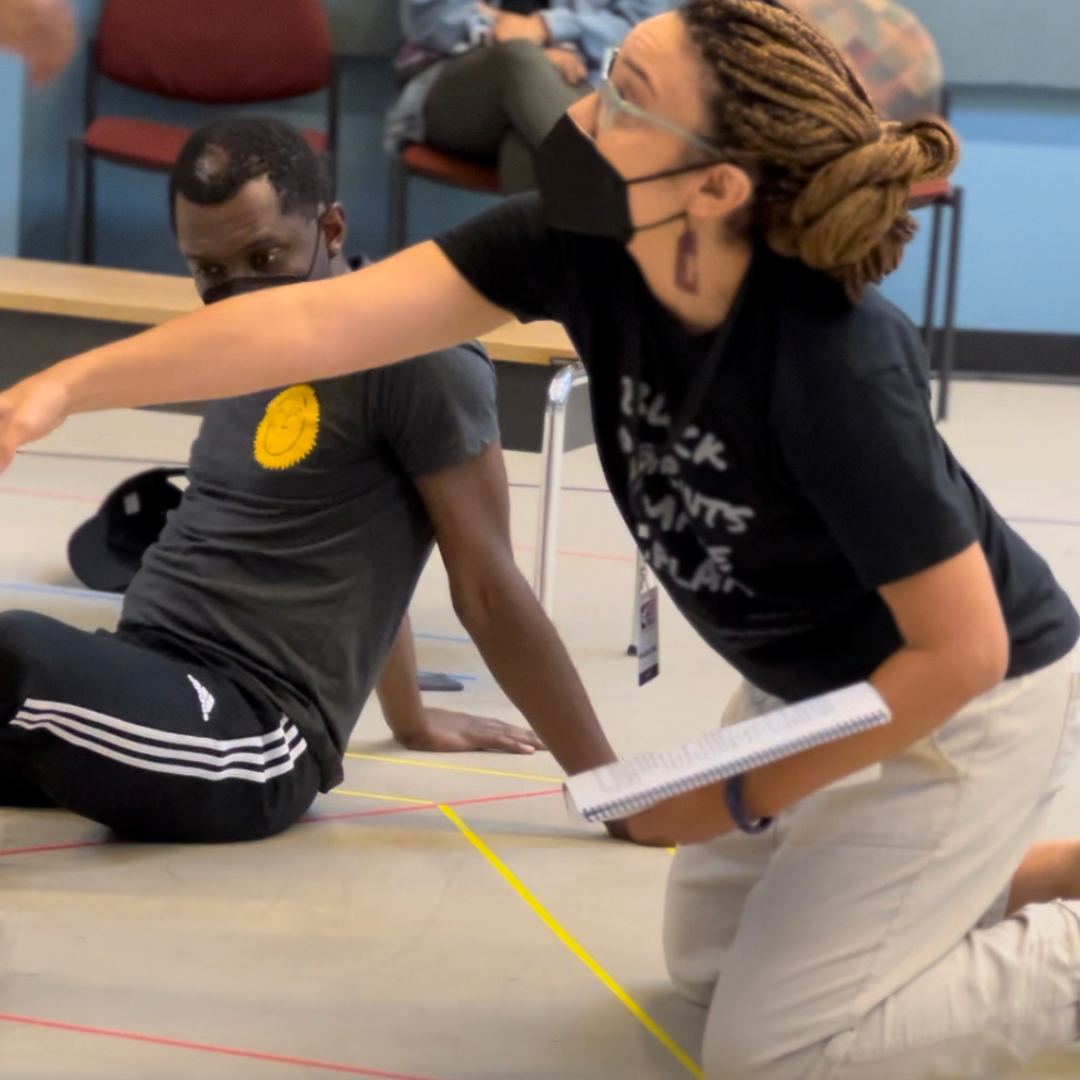

Kaja Dunn: Thank you. I’m working on Choir Boy with director Jamil Jude for the second time. We mounted the first production at Denver Center in April, and now we are at ACT with a co-production with The Fifth Ave. Theatre. I’ve wanted to work with Jamil for years. He curates beautiful rooms. We’ve talked and dreamed, so this was an exciting opportunity. It was also an all-Black creative team.

Ann: How did you train for this moment and the work you do?

Kaja: It was a combination of things. I had all the movement principles and have done fight choreography. I also worked as a director and did work in race and theatre. Consent was part of that work of thinking about better techniques. Back in 2012, I had consent and boundary clauses in my acting class syllabi. I started training in fight choreography in grad school and found many of the environments to be unhospitable to myself as a Black woman.

Then I spent a lot of time in my work thinking about how all of these things intersect. My way into intimacy choreography was to do work on how race affects consent and boundary practices. In 2019, Theatrical Intimacy Education (TIE) approached me for help diversifying their student base, and I asked what they had that targeted choreographers of color. I was previously affiliate faculty in Africana Studies at University of North Carolina Charlotte, so the crossover between sex in performance and race was one I had been thinking about. I have since taught Race and Choreography to several hundreds of intimacy professionals and students.

I would rather be there late than not at all because I think it’s important.

Ann: Tell me a little bit about some of the roadblocks you have come in contact with. For example, when you've been called in late on a project, tell me about the impact on a cast and on you as an artist when that happens.

Kaja: I think this happens in a lot of different ways. Sometimes it’s about a creative process. Sometimes someone wasn’t a good fit for the team. Sometimes it’s a disparity between culture of the creative team and the story they are telling. Sometimes it's a desire for effective training or a discussion. People decide, “we should also add this intimacy piece,” and I'm always grateful to be in the room. I would rather be there late than not at all because I think it’s important.

My research is in intimacy of the global majority with a focus on Black sexuality and race and intimacy. People tend to think of intimacy in terms of gender and orientation and forget about the racial element.

The earlier in a process you are brought in, the more fully you can do your work. What becomes hard is people don't see their blind spots, and they want you to talk about this thing. But you haven't been there to help develop that thing, and they're not realizing what's missing.

It's always nice to be able to be there at the beginning of a discussion or creative process, and in most of my work I have been fortunate that that is the case. I think the times where it becomes most problematic is when people really have not been thinking about race at all.

Ann: I was just working on a show, and there was a Black actress and Latina actress who had a kiss. We were not even getting physically situated to kiss. We were talking about the kiss, and the Black actress just burst into tears. We stopped everything, of course, and we let the tears flow. Then I said, “Okay, we've hit a boundary of yours, and this is a beautiful moment. Can you talk about what you're going through?” She said that she got embarrassed every time she had to kiss a person lighter than her, because her makeup would get all over the lighter skinned person, and it would be crushingly embarrassing for her to do kissing scenes because she didn't want the other actor to have her makeup all over themselves.

I just said, “Whoa, Whoa! Okay. So, this is something that is completely fixable. You are not alone in this. We have setting powders. We have setting sprays. We have all these things available to you, and we are going to make this part of the journey something that is going to be a healing moment and a moment of success for you.” We were all just in tears because of the relief of pain of that. So sometimes we walk into a place where it’s not the just sexual content, but race and sexual content and shame and Eurocentric training.

Particularly with Black intimacy professionals or Black feminist thought, there has been a lot of extraction. So there's an importance to saying, “Please cite my work or include me.”

Kaja: Yes. It's not just being able to do the choreography. It's research, dramaturgy, and lived experience. This is something we've talked about before: boundaries are also around cultural practices or what you share culturally. That means if you're creating a space of cultural inclusiveness (often in a predominantly white area), have a resource sheet with a barbershop list and other things to help folks navigate. Technically, things like this aren’t exactly part of my job, but they become part of the work I do. Most of the time I’m collaborating on how we can help people be their full selves and do their best work.

Ann: How do you find balance? Do you practice any rituals before you get into the work? How do you create self-care space around your psyche and around you?

Kaja: When I go into spaces, I'm bringing a community with me. You know this from working with me. I will say people's names—the Black artists, feminists, and scholars who inspire this work, the other intimacy professionals I have worked with and learned with.

On the other side of that, I have really begun to ask for people to cite my work and recognize the work of other Black scholars and artists when they use it. There is sometimes a level of extraction and appropriation. Particularly with Black intimacy professionals or Black feminist thought, there has been a lot of extraction. So there's an importance to saying, “Please cite my work or include me.” I also champion hard for anybody I know in my community and have mentees and people shadow whenever possible.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here