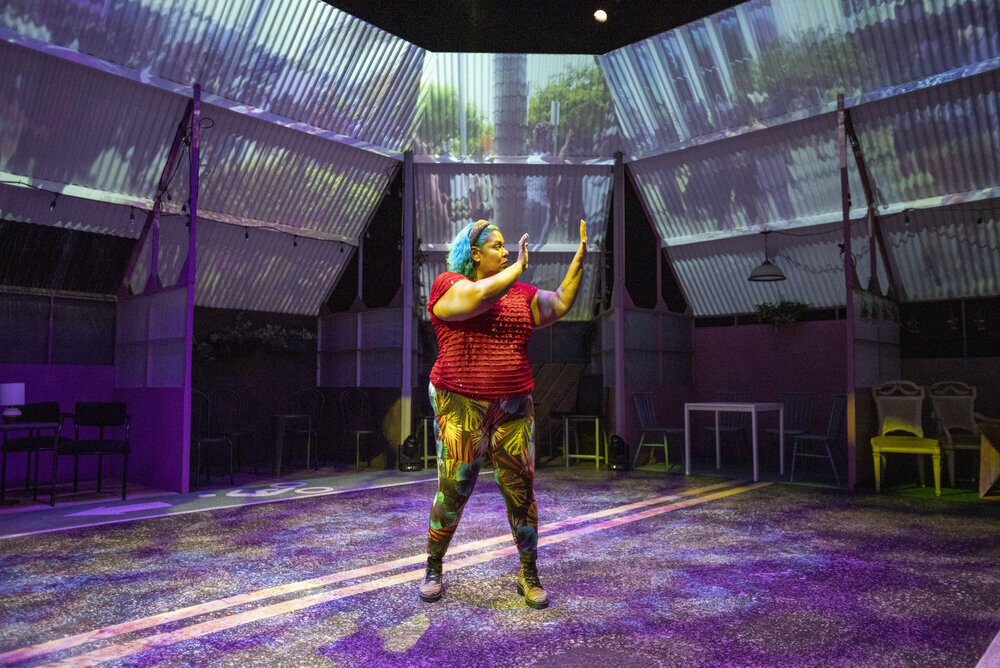

“This is not a play,” pronounces actor Florinda Bryant in the opening lines of Cara Mía Theatre’s production of Virginia Grise’s performance Your Healing is Killing Me (23 September-10 October 2021), directed by Kendra Ware in association with a todo dar productions. I am in the audience seated on a folded chair at a small table among a dozen partitioned tables at the Latino Cultural Center’s new, multiform black box theatre in Dallas, Texas. The booth-like seating, dim lighting, and small audience capacity evokes the feeling we are at an intimate grassroots coffee shop—perhaps New York City, where Ware situates the performance. With the exception of Bryant, we are wearing masks. The seating design, even as it is intentionally socially distanced, allows for intimacy: We are in the Delta variant surge of the many surges that have pressed on during this global pandemic which have—along with other racialized, economic, and health crises—disproportionally impacted Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) communities.

Grise wrote Your Healing is Killing Me long before the COVID-19 global pandemic. The performance offers Grise’s autobioethnography of seeking care and healing from debilitating eczema and an auto-immune disorder in health care systems not invested in BIPOC health. Across eight sections, Bryant manifests through movement Grise’s narrative of the intersectional and structural (race, economics, gender, and sexuality) traumas and histories that shape BIPOC communities’ access to health care. While watching the performance, it is difficult not to situate these inequities, and the need for collective self-care, amidst our current COVID-19 pandemic and the disproportionate impacts on people of color.

Your Healing is Killing Me is a movement manifesto grounded in grassroots health activism by and for BIPOC. In the piece’s opening moments, Bryant—donning a shimmery red blouse, blue hair underneath a yellow headband, geometric-patterned colorful pants, and maroon boots throughout the show—stands tall and states: “This is a Manifesto. Towards A Politic of Collective Self-Defense. Instead of Individualized Self-Care.” To activate the performance’s collective self-defense, Bryant performs the eight movements from Chairman Mao’s 4 Minute Physical Fitness Plan—walk, reach, punch, present the bow, kick the door, side stretch, toe touch, to the heavens, jumping jacks, and run—as a way to introduce them. She then performs each of the movements in their entirety across the piece’s eight sections. These collective self-defense movements contrast with the actor itching her elbows, knees, and legs throughout the performance. The actor’s itching embodies many traumas that Bryant names throughout the show: sexual violence, the violence of capitalism, racial violence, and the layered impact of these traumas on BIPOC.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here