That, to me, resonates as the value of Theatre in the Dark, both as a performance and as an artistic process. It forces both theatre practitioners and patrons to think about meaning in a totally different way. In a traditional theatrical setting, non-visual stimuli is, if used at all, a means to add to an already existing narrative; for example, the Tooting Arts Club chose to bake pies and serve them to the audience in their production of Sweeney Todd. However, in Theatre in the Dark, the non-visual stimuli become as much a part of the narrative as blocking or choreography is in a traditional work. The form—choosing to reach forward in the dark and accept different tastes—becomes the meaning: seizing the day.

Creating Multisensory Theatre Experiences

Erin Mee began actively brainstorming ways to make theatre in the dark after she attended a performance by Teatro Ciego in Buenos Aires. At Teatro Ciego, which roughly translates to “Blind Theatre,” performances happen in total darkness. About half of their actors are Blind or visually impaired, and the company strives to create work that is inclusive to audience members who are Blind as well. This inclusivity brings new audiences to the theatre and new voices into the creative process, further deepening the art that is being made.

Pieces that centralize a multisensory nature mean more traditional barriers to entry are stripped away. This is one of the major draws of multisensory theatre: it can often be more accessible to those with disabilities. Many theatremakers, for example, construct multisensory theatre to specifically be more accessible to the autistic community while others, like Teatro Ciego, focus on creating work for the Blind community.

Multisensory theatre can also allow for a more open and less literal interpretation than a traditional piece of theatre. For example, a recent project called Famous Deaths—created by Dutch artists Frederik Duerinck and Marcel van Brakel—invited their audience to lay down in a mortuary chest and experience, through smell alone, what the last moments of a famous figure’s life was like. This project is documentary theatre in a very non-traditional way and invites the audience to engage with the figure being studied on their own terms. Additionally, Famous Deaths is accessible to a wide variety of abilities with few barriers to entry needed outside of the ability to smell and get inside a mortuary chest.

Pieces that centralize a multisensory nature mean more traditional barriers to entry are stripped away.

The Theory of Rasa

The performance Mee attended in Buenos Aires led her to send off emails to her own company members about developing a work done in the dark. During the first workshop, held in March 2019, participants—of which I was one—were lead through a short version of what would become Theatre in the Dark: Carpe Diem. Mee refers to the show as the literalization of her theories around the concept of “rasa”—meaning the act of relishing, according to the ancient philosopher Abhinavagupta—in interactive performance.

In an essay she wrote for HowlRound on the topic, Mee argues: “Rasa is active, sensorial, and experiential. It involves the active taking in of the performance. It posits the audience as participant and partaker.” This is Theatre in the Dark in a nutshell. Tastes and smells that would, during an average moment, be experienced passively are elevated to being relished. The audience begins to really interrogate their own senses and savor what they are taking in. This is not only Mee putting her theories into practice; it is also the next step of the This Is Not a Theatre Company manifesto, which states, “I like theatre that feeds me, but that asks before doing so because, you know, sometimes people have food allergies. I like theatre that smells, and tastes, and has textures I can touch.”

I’ll admit that as a company member, I was a little doubtful when Theatre in the Dark was first proposed. How could we possibly begin to make live theatre without any visuals? But it isn’t as radical an experiment as I had initially assumed. Instead, it is the next logical step in multisensory theatre and This Is Not a Theatre Company’s specific commitment to playing with different senses.

Process in Performance

“Performing” Theatre in the Dark is an almost balletic experience—three other company members and I navigate the relatively small playing space—there are about ten blindfolded people in the audience per show—dropping off different tastes and performing live ASMR by whispering specific phrases in the audience’s ear. We weave in and out of tables, around each other, and in-between chairs. The process is colloquially called “Viewpoints-ing” by the company, after the Viewpoints movement system popularized by the SITI Company, where performers have a high level of awareness of their surrounding and know how to navigate the space. This understanding is essential to performing in Theatre in the Dark.

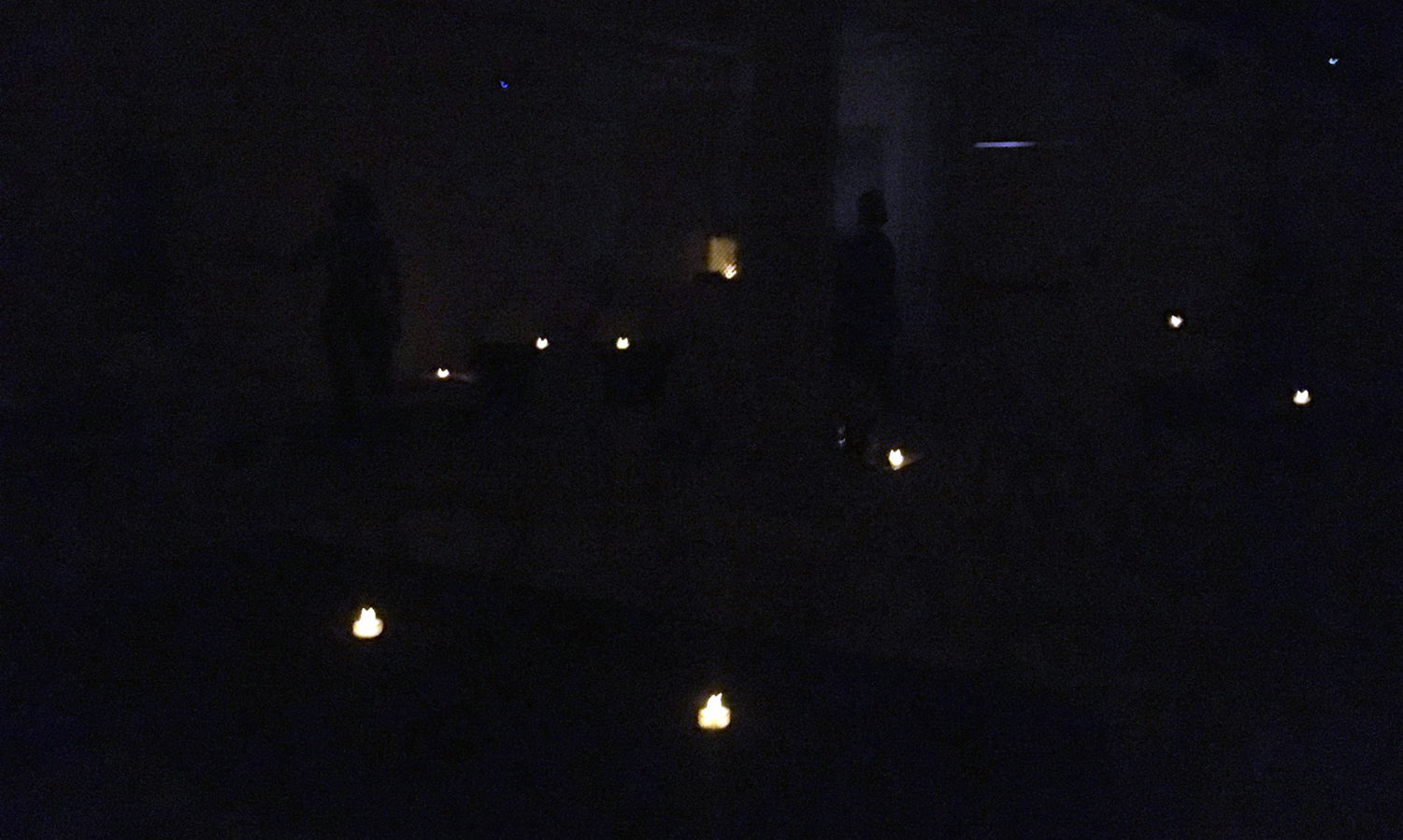

To ensure the performers can keep track of what is going on, the play is performed in low light: two electric tea lights sit at each table, and there’s one tea light for each props table. While I was initially concerned about how little light there was going to be, I was stunned by how much my eyes adjusted. By the end of the performance, I could see almost as if it was in the full light of day. This is notably different from Teatro Ciego, which is done in pitch black and whose audience is not blindfolded.

How hard can it be to walk a blindfolded person into a room? As it turns out, this act is as important a moment of intimacy as any romantic or sexual scene onstage.

In the past, my work with This Is Not a Theatre Company was confined to acting as dramaturg or co-creator for their shows; never before had I performed in a production. What amazed me the most was how much thought goes into very small but vital details of audience engagement. We rehearsed how to walk the audience in, how to sit them down, how to whisper in their ears, and how to drop off all of the different items to taste—small plastic shot glasses filled with liquid and pieces of food.

A lot of this rehearsal initially seemed to me like it would be common sense. I mean, how hard can it be to walk a blindfolded person into a room? As it turns out, this act is as important a moment of intimacy as any romantic or sexual scene onstage and needs to be choreographed with the same level of care and specificity. The audience members are asked to give up a lot of control—they don’t know where they are, who is leading them, or what they will be asked to do. So it is essential that the performers let them know they are safe.

We discovered the best way to let the blindfolded audience members know we were going to guide them to their seat was to place our hands at their elbows and gently slide our fingertips down to their hands. Once we had their hands, we walked them slowly over to their chair and then gently placed their left hand on the far edge of the back of the chair (so they know where the chair ends) and the right hand on the table itself. Using this method ensures that audience members know where the chair is, what the distance between the chair and the table is, and—most importantly—that they are safe because the performers are taking care of them.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here