There is no one way to create a puppet show. Some people write a script, some devise collaboratively and use notes as aides, others utilize storyboards or improvisation, and yet more adapt an existing story or human script (scripts for performances given solely by human actors or performers). All these routes are correct: if it works, it works. However, as co-founder of Croon Productions, a small-scale UK company specializing in puppet shows for grown-ups, I know that one thing theatremakers must often consider is space.

“Space” is defined by the online Cambridge English Dictionary as “an empty area that is available to be used... the area around everything that exists, continuing in all directions... the distance between.” When it comes to puppetry, this can include:

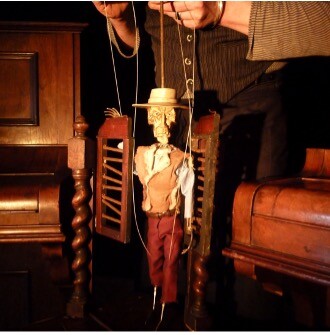

- The space or distance on stage between the puppeteer and the puppet (literal space or air between the two, but also the metaphoric space between the human world and the puppet world).

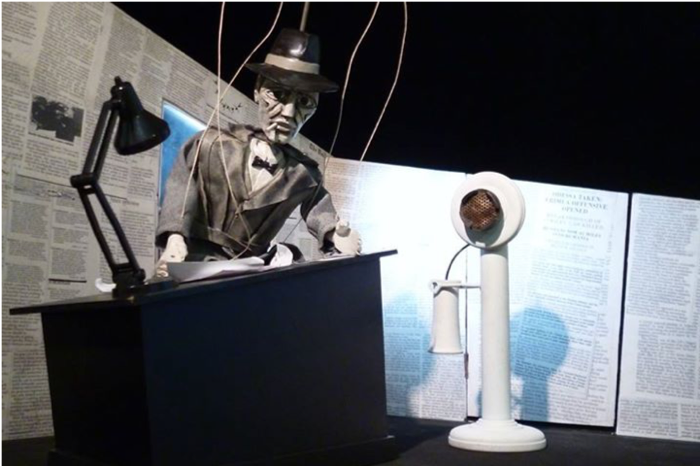

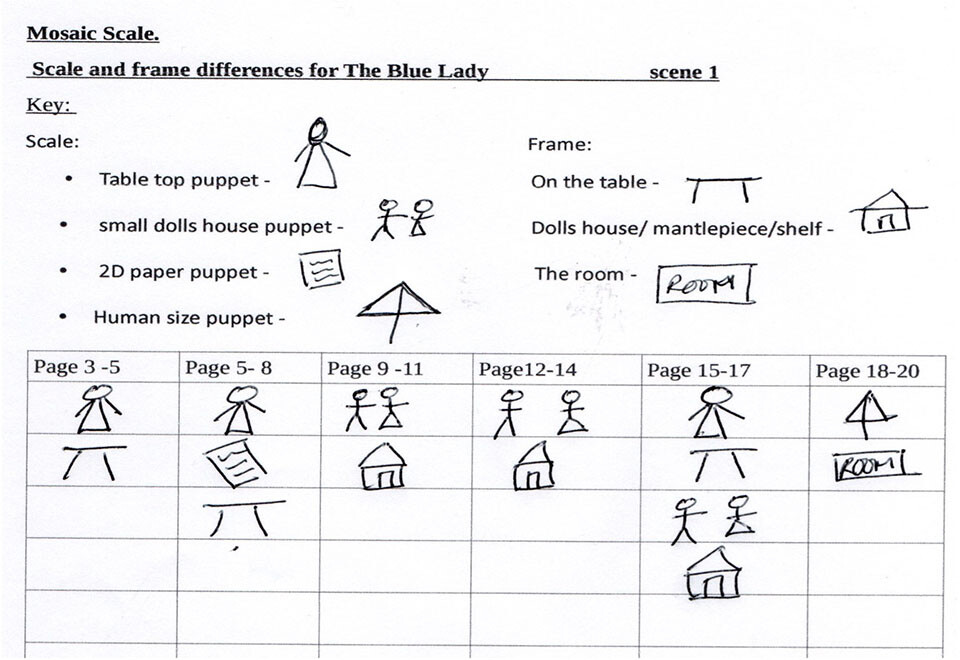

- The space on stage and how it changes in the audience’s perception if theatremakers play with different scales of puppets, sets, and playboards, as well as different frames (as in what the puppetry is framed by—a proscenium arch, humans, a piece of furniture, a large theatre set).

- The imaginary and intellectual space or distance between the puppet world and the “real” human world.

- The space the show is being performed in (both the type of stage/performance space and the size of that space).

The space a puppet show creates is the puppet world. Space on stage is about balance, rhythm, choreography, and the pictures created for the audience to experience. A visceral and uncanny response to puppetry is the space between what we perform as puppeteers and what the audience perceives. The concept of space in puppetry matters because space is perspective, both literally and figuratively.

Croon’s most recent piece, Spaghetti: a Western, grew from an original idea for a show performed in and on two upright pianos. These pianos would be cut into smaller sections so they could be moved around to create different settings or joined together to both store props and puppets for transportation and to act as playboard (the term “playboard” originates from the board at the front of a puppet booth that the puppets “play” on and can be almost anything a puppet can perform on: a table top, a human body or a shadow screen). This exploration of the space we could use—to create different places within the story, different levels to perform on, and different frames for puppetry performance, and as a useful box for transportation—was for us a game changer.

I believe dramaturging space can help puppetry theatremakers look at their work in new ways. As part of my recent doctoral research in writing and dramaturgy for puppet theatre, I have created an active, practical, five-step dramaturgy system for puppet theatre: the Mosaic Scale. Each step of the Mosaic Scale allows puppet theatremakers, writers, directors, or dramaturgs to ask questions of their process, ideas, and decisions.

The concept of space in puppetry matters because space is perspective, both literally and figuratively.

The Mosaic Scale Five-Step System and Exercise

The Mosaic Scale can be be dipped in and out of, and the steps don’t have to be read in a linear way. It’s akin to a mosaic-building approach, designed to help refine and create the bigger picture of a puppet show and to ask the questions that lead to the decisions, which makes the puppet show the best it can be.

- Initial Analysis: Analysis of decisions on style, format, and story.

- Repeat and Revisit: Considerations that are revisited throughout the process, including design, puppet type, scale, and size.

- The Visceral: Considerations that encourage a visceral response to the puppets and puppetry.

- The Uncanny: Considerations to encourage an uncanny response, over and above the sheer uncanniness of puppets.

- Phenomenological Overview: Considerations of the experience of and the response to the puppetry for both puppeteer and audience.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here