Representation Behind the Scenes

With Betty Shamieh & Tracy Francis

Nabra Nelson: Salaam alaikum. Welcome to Kunafa and Shay, a podcast produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. Kunafa and Shay discusses and analyzes contemporary and historical Middle Eastern and North African, or MENA, theatre from across the region.

Marina Bergenstock: I’m Marina.

Nabra: And I’m Nabra.

Marina: And we’re your hosts.

Nabra: Our name, Kunafa and Shay, invites you into the discussion in the best way we know how with complex and delicious sweets like kunafa and perfectly warm tea, or in Arabic, shay.

Marina: Kunafa and Shay is a place to share experiences, ideas, and sometimes to engage with our differences. In each country in the Arab world, you’ll find kunafa made differently. In that way, we also lean into the diversity, complexity, and robust flavors of MENA theatre. We bring our own perspectives, research, and special guests in order to start a dialogue and encourage further learning and discussion.

Nabra: In our second season, we highlight US MENA theatremakers with an impact nationally and internationally. This season outlines the state of MENA theatre today through the lens of multigenerational and multidisciplinary artists.

Marina: Yalla, grab your tea. The shay is just right.

Before we get into today’s exciting episode, we wanted to give you a quick update of what’s going on in our lives as we start season two.

Nabra: I got married in July 2021 to my wonderful partner, Daniel Podgorski, who runs his own blog and website called The Gemsbok. I’ve been writing plays during quarantines a lot. I’ve been doing EDI consulting more and Theatre of the Oppressed work, both of which I really love. I’m still working at Seattle Rep and growing the local Seattle MENA theatre company, Dunya Productions.

I recently redid the Nubian Foundation website, so check that out, and continuing to do work with my mother around Nubian cultural awareness, both nationally and internationally, through that organization. My brother and dad are also getting more involved in working on some exciting projects as a family. So, stay tuned.

Marina: Very exciting, Nabra. So, I worked on As Soon As Impossible, a play by Betty Shamieh, directed by Samer Al-Saber at Stanford. I was an assistant director and dramaturge on that project, which was lots of fun. Egyptian actor Khaled Abol Naga was in it. It just was a great process to work on.

As always, lots of research here in PhD life. I’m in year two. We have a qualifying exam that I’m writing, and it’s about Jerusalem and the Miracle of the Holy Fire in the 1800s. So, it’s more exciting than it sounds. I just discovered Christian hajjis, so that’s a thing. Let’s see, what else? I have been taking tatreez classes, so Palestinian embroidery classes. I’ll link her here so you can find out more about Tatreez and Tea. She [Wafa Ghnaim] is an amazing historian and researcher and craftswoman. She has set up at a lot of different institutions that are amazing, but her classes and just the community she creates have been such a wonderful and fulfilling place to learn more about Palestinian embroidery and also to practice it. So, if you’re interested, definitely check out her site.

I’m also intimacy directing a play right now on Stanford’s campus. I presented a paper at the American Society [for] Theatre Research around pilgrimage and some of the barriers that Palestinian Christians face as they’re trying to do things that pilgrims from outside of Palestine are able to do in Palestine. I’m working as a dramaturge on some new work. So very exciting stuff.

Nabra: All of your projects are so interesting. I want to see them all. We’re so close yet so far away.

Marina: Nabra, that’s how I feel about your work too. I love it.

Nabra: We both love each other so much.

Marina: It’s true. Nabra let me read one of her new plays, and it’s so good. Oh, I can’t wait to hear where it goes next.

Nabra: Aw, thanks.

Marina: Yes. Also, we got through all of season one without talking about the music. We realized, “Oh my goodness! No one knows that this is quite relevant and close connection to Nabra and her family,” which is, I think, really exciting.

Nabra: The music is by Hamza Alaa El Din, who is my great uncle. He’s from my village, the village of Abu Simbel. So that’s a really traditional, folkloric, Nubian music by a very famous Nubian musician. Many of his songs were written by my grandfather, Mohy El Din Sherif. You can find a lot more of his music anywhere on YouTube, everywhere. He’s extremely prolific and toured internationally. I wanted to point that out, enjoy that music. We had one other thing we wanted to touch on before we jump into the interview.

Marina: Yes. Okay. So, we call our podcast a “MENA” theatre podcast. MENA standing for Middle East and North Africa. This season will have artists on who identify as MENA. Some who identify as SWANA, Southwest Asia and North Africa and others who identify as SWANASA, which is Southwest Asia, North Africa, and South Asia. Those are different terms that you will hear, and that will come up. While we are not going to necessarily get into all of the nitty gritty of these different identifiers, we just wanted to sort of mention that we’re going to be using slashes to really be as inclusive as possible and to defer to terms that people themselves are using. But it’s actually kind of a complicated conversation, and hopefully we have it at some point on the podcast itself. But I wanted to clue you into what we were doing this season.

Nabra: Last season, we talked about onstage representation in contemporary theatre. But what does representation look like behind the scenes and why is it important onstage and off? In this episode, we are joined by playwright, Betty Shamieh, and artistic director of Boom Arts, Tracy Francis, as we discuss the production process and new play development.

Marina: So now about our interviewees, here’s a little bit about our guests for this episode. Betty Shamieh is an Arab-American playwright. Her American premieres include The Black [Eyed] at New York Theatre Workshop, Fit for Our Queen at the Classical Theatre of Harlem, The Strangest at the Semitic Root, Territories at Magic Theatre, and Roar at the New Group. Selected as a New York times critics’ pick, Roar is the first Palestinian-American play to premier off Broadway and is widely taught at universities throughout the United States. A graduate of Harvard College and the Yale School of Drama, Shamieh was named a Guggenheim fellow, UNESCO young artist for intercultural dialogue, Denning Visiting Artist at Stanford University, and a Radcliffe Playwriting Fellow. She was recently commissioned by Noor Theatre to adapt Roar into a comic television pilot. Currently, the Mellon Playwright in Residence at the Classical Theatre of Harlem, her works have been translated into seven languages.

Nabra: Tracy Cameron Francis is a first-generation Egyptian-American director working across different disciplines, genres and mediums, including the development of new plays, works in translation, site-specific performance, multimedia performance, and film and TV. She’s currently the artistic director of Boom Arts, and formally, was the co-founder and artistic director of Hybrid Theatre Works. She was a 2017 TCG Rising Leader of Color fellow, is a core member of Theatre Without Borders, and serves on the steering committee for the newly formed, MENATMA.

She holds a BA from Fordham University in Middle Eastern Studies and Theatre, and is a member of the Lincoln Center Director’s Lab, and an associate member of SDC. As a freelance director, Tracy’s work has been seen in theatres across New York, regionally in Oregon and Massachusetts, and internationally in Egypt, Rwanda, and Italy. Tracy has developed new work through stage readings and workshops at numerous theatres. And as an interdisciplinary artist, she has created original performance art, merging movement and video and text. She has worked in television as a shadow director for True Blood, and as an intern for Saturday Night Live. She currently serves as the festival director of the Cascade Festival of African Film, which is the longest running African film festival in the US.

Marina: Betty and Tracy, we are so glad to have you here. We talked about representation pretty broadly in our first season, and we’re hoping to dive more deeply in today, especially given your expertise. We know that conversations around representation can get super hypothetical, but hopefully we’ll be able to dig into the specifics as well.

Nabra: So, we’d love to start with you, Betty, as a playwright, kind of the beginning of all conversations about representation. We wanted to ask: when your plays are produced, how do you approach representation from the standpoint of a playwright? Especially when you’re developing a play, how important is it to you that the person in the role is of the same background as the character, in addition to your creative teams and kind of the general conversations around your plays.

Betty Shamieh: Thank you so much. I think this is, for me, a very interesting question because it has kind of evolved over the evolution of my career and the evolution of American theatre. And the Arab-American community, like the Latinx community, representation is not black and white because we are not Black or white. We’re everything in between, and we pass as people of color, as white people. One of the preeminent figures of American television was Danny Thomas, who was an Arab-American, who passed as a white person. Same with Jamie Farr, who was in M*A*S*H, passed as a white guy.

When I was in graduate school, and I realized a lot of the HowlRound articles I write—because I’m a playwriting residence [at] the Classical Theatre of Harlem, I have this obligation to kind of interact. But I’ve been doing it more than I’m required because it’s such a wonderful platform to be able to connect with what I feel like is other versions of me and younger versions of me who are on this platform. By that, I mean theater artists who are trying to deal with people, being a person of color and what that means in a changing environment.

So, to come from a community like the Arab-American community who has a history of passing as white, my primary obligation, I felt, was to cast people of color. That was in the early 2000s when I was coming out of school. That was my priority because I really felt it was important to cast people of color in general. Also, I was the only Palestinian, or one of very few Arab-Americans who was in graduate school, studying playwriting. I got it out in 2000, and in New York there was no community.

For me, having been embraced so warmly by the African American and Latinx community to feel like, “Oh, suddenly, now I’m Arab-American,” and if you’re a quarter Lebanese, I have to cast you as opposed to somebody who is Latinx, who comes from a community that afforded me opportunities that were basically earmarked for their own community. They were generous in that way. I felt when I was in a position of relative power, that I should model that kind of inclusivity for people of color, as opposed to specifically my people of color because my people of color have been passing as white people for decades. But I have to say one of the singular sensations of my life was getting to work with Khaled Abol Naga, who is an Arab-American—is an Egyptian. Basically, he is a movie star. He was the Brad Pitt, I think, of the nineties. He really is an iconic Arab in the Arab world and done some of the most important and interesting work in Egypt, which is the Hollywood of the Middle East, essentially.

Even though I developed that play and that part for Jamie Farr of M*A*S*H, and it was developed at Second Stage, and he actually did the workshop. It’s the fact that he, as an Arab-American, playing an Arab was too far of a jump for that character. To actually have a man who is an Arab and speaks with an accent that is his own accent playing that role was a revelation for me. It made me rethink this idea of representation in a new way. That evolution of being a young person who was embraced by the African American and Latinx community when I had no community or felt like I had no community for decades before I got my footing in the world to feeling like, “Wow, there is this kind of real essence and authenticity,” that even casting an Arab-American in an Arab role, I did not achieve with the same sort of deep sense of comfort that he was embodying who he was, which was a man who English is not his first language.

And so, I just found that to be a revelatory, an important thing for my own development. And who and what gets to be people of color in American theatre or in Hollywood? It changes. I feel like I’m just riding the wave of those changes. Also, coming back to questions of, “What is an authentic? I am born in America; I write in English. Am I a Palestinian in diaspora writing? Am I an Arab-American? Am I just plain all American just like any other hyphenated person?” One of the things I’m doing now, for the first time, is doing, and it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done is I’m working on a play about Native Americans who attended Harvard in the 1600s. It’s a story nobody knows anything about. And for me to kind of represent the Native American experience has made me come up with all my own biases about representing other people, and how important it is to have a writer from a certain background.

Even though my entire career, I have been shepherded and helped by people like Wallace Shawn and other writers who are white but who write with an activist voice. I think that’s something that’s very important to me. I’m an activist. My work is part of my ethos as a citizen. I think that that sometimes in this idea of who is representing us and what kind of stories we tell. Naomi Wallace is a deeply radical writer in a way that many people who classify themselves as Arab-Americans are not. She writes about Gaza, and she writes about intense stuff. She got a MacArthur Genius grant but probably would have a different career if she wasn’t an activist writer. And so, for me, representation is not just about who your grandparents are and what they spoke when they came here; it’s about your ethos as a person in the world, challenging the status quo or challenging the narrative that are deeply ingrained in the American theatre.

Marina: Thank you, Betty, for that answer. I mean, you got into so much of the nuance that we’re really trying to highlight in this episode in such a wonderful way. Thank you. It’s a wonderful way to start us off. And Tracy, well, take the same direction to you as a director. What do see as your responsibility around representation, especially in new play development?

Tracy Cameron: Just starting with new play development, I feel like it’s almost more important in developing new plays. Especially over the last couple years, since rehearses have been shut down, I’ve been doing a lot of workshops of new plays. And especially, so just you know, since we’re on a Middle Eastern podcast, I’ll speak to that.

If it’s a play with a lot of Arab-American or Arab characters, I think having actors who are familiar and personally with those cultures helps the discussions in new play workshops because we’re able to dive deeper into the nuances of the play and the characters and what it means culturally and be more specific with it. Because in maybe a new play development workshop, you may not have a public showing of it, but by deepening those conversations and having folks who can speak personally from the perspectives of those characters or those cultures, I think... Betty, you can tell me if this helps with playwrighting, but I feel like those deepen those conversations around the plays. And so, we can actually have those honest conversations about, “Is this play really representative? Are these characters true to this culture?”

I did a workshop, or it was an audio play of something that was around characters. It was a really specific culture, but the writer was a white writer. I was very, very clear that we had to have actors from those backgrounds. And thank God I did because they were able to help reshape that play and make it authentic. It was a lot more work because there was a lot of rewrites that had to happen and just deepening of that to make it authentic and to bring those voices into it. When I can, I try not to work on projects like that, but occasionally, that happens. And so, when it does, I try to make sure that the folks in the room, as many of them as possible, are from those backgrounds or have that history that’s in relation to the play and the work.

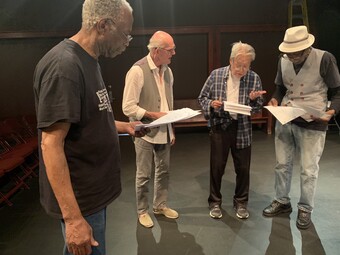

Betty: I just want to let whoever’s out there know that Tracy and I have a long history together because we actually… When I was working with Sam Gold on the off-Broadway premier of The Black Eyed, we made it a point to go and find a young Arab-American director with the chops to be the assistant director on a new play that was incredibly experimental and very public in how it got to the stage. It was wonderful, but it was also an exercise in that there were people out there, if one was willing to look and to give opportunity to not the usual suspects who were coming out of the usual programs. I think that it’s something that I’m going to continue to try to make a commitment to in my own work, moving forward.

But it’s also a different environment. Now there’s a wonderful amount of people like Tracy in the world who are doing such amazing work and at very high levels, and in positions of power at regional theatres, which is not something I could ever have imagined, ever, coming out of Yale drama. If you told me a guy named Joe Hajj would run the Guthrie, I’d be like, “That’s not possible.” You know what I mean? Because that was the narrative that I had, which was that “This is run by white people and they give us a slot as opposed to we are the taste makers.” It’s a different environment and one I could not imagine coming out of school. I talk a lot about graduate school, and I think that that’s very funny because I’m a relatively mid-career playwright, I’m a mid-career person, I’m a mid-age person. All these things that ... Don’t tell anyone, I pretend to be fifteen years younger. My son doesn’t know my real age, which is hilarious to me, but that’s how I roll. He will find out, I’m sure, as anybody who Googles me can find out. But the point is: it’s a different, different world than what I came out of.

There’s all these people and all this push for representation. And I do have to say, I think a lot of it is thanks to the work and the advocacy of the African American community who has made room for other people of color while still bearing the brunt of microaggressions in artistic spaces. I think we owe a huge debt to them for articulating the changes that need to happen in American theatre for it to not be a static, dead art form.

Nabra: Thank you so much. You’ve brought up actually a point I wanted to go a little bit deeper on, which is kind of how attitudes have changed. You’ve already shared a lot about your experience since starting your career up until this moment. It’s exciting that you’ve acknowledged, as well, the different communities who have made this possible and have kind of paved the way for our community to be able to push for more accurate and broader representation. In the past, I think a lot of us may have opted for a play to be produced without accurate casting, since that felt like, or in some cases, really was not possible for certain communities or for a certain theatre. But now, there are so many resources for accurate casting, a lot more connection through technology for different communities to connect with each other, and a lot more understanding of the importance of representation.

How do you feel that agency for especially MENA theatremakers has changed our agency to demand representation, and what are other elements that have made that possible? How do we balance that need for our stories to be told broadly in communities that don’t see our stories very much while we’re trying to balance making sure that representation onstage and behind the scenes is strong and is supporting that storytelling?

Tracy: Let me jump in. Just thinking about how Betty was talking about earlier, just how things have shifted so much. Even five or six years ago, if I approached a regional theatre with a play, let’s say with a bunch of Middle Eastern actors, they were like, “Oh, we can’t cast that here. Sorry.” And they were just hard no, or like, “Can we cast all white people?” I’d be like, “That’s also a hard no.”

I feel like now, because there’s these movements happening like, as Betty was saying, from other communities as well, that there’s a dialogue that’s been happening nationally. I feel like there’s that sort of not pressure, but there is more awareness around representation and making that effort to, “Do we have to fly actors in from somewhere else? Instead of just shutting down this production, how can we make this happen and how can we do this well in making sure we have that representation, not only on stage, but also backstage?” I think that’s also where the conversation has shifted also in the last couple years because before it was like, “Make sure that the things that the audience sees is represented, but all of our design team and all of our backstage folks are not going to be any representative of the cultures of the play.” And so, I feel like there—it has been somewhat of a shift with that, but not as much as there should be.

I still see even Middle Eastern companies, for example, will still be hiring white directors to direct Middle Eastern plays. That still happens. I also feel like somehow predominantly white institutions have been making actually even more of an effort, because they’re somewhat worried about their image honestly, to be more representative.

Betty: Yeah. I just want to second what Tracy said and also say that I got to work with Samer Al-Saber at Stanford. And working with somebody who you have that comfort level in terms of representation is very, very important and so, so critical for the development of a new work.

I’m very, very excited that these conversations are happening, that people are responding. For ten years of my career, I was predominantly produced in Europe. In Greek… there’s really not a lot of Arab-Greeks. There’s just no way you can go to Greece and be like, “I’m sorry, you’re not casting any Greeks.” Especially because it was crickets, I had no productions of these plays, a couple of which were done in translation but have not been produced in English, which is so weird. That’s not normal. You’re not normally produced in translation before you’re produced in the language you wrote it in. And that’s just a testament to how difficult it has been as a Palestinian or an Arab-American who writes with an activist voice, and who insists upon not creating war porn. You know, that has been the trajectory.

It’s very, very challenging for me, and I’m not the only one. Somebody wrote an article that I really wanted to write, Larissa Fasthorse. She said, “Every time there’s a big hullabaloo over a white person being cast in a people of color play, I can feel”—and that’s how I feel too— “my play being thrown in the garbage across the country and literary magazines.” Because it’s easier to go and do an all-Black play with a Black director and feel really good about yourself than it is to do a Betty Shamieh play, which is hard to do anyways because of the political environment, and then have to deal with blow back because you cast an Italian or you cast a white person in one of the roles.

One of the things I’m really proud of myself is I gave, in my play, Roar, a young woman who had never had any acting experience an off-Broadway premier. That was a choice I made, and it was something that I committed to. I said even if this person has never been able to carry a role on the off-Broadway level, if I’m going to be at that level, I’m going to take at least one person with me. But the expectation that you can do an off Broadway play and have an entirely new cast, who’s never worked on that level, never carried a full role was the expectation, I think, in certain environments.

And so, like Larissa Fasthorse, I do feel that there is a real importance in saying, “Why are you tagging people who are trying, you know, at universities who don’t have the entire cast?” It’s interesting to me. I think we have to really be cognizant and careful about how woke-ism talked about in an environment where Palestinians have to leave the country in order to be produced. I think that it’s a hard thing to say, especially a hard thing to say to the Arab-American community. But I think it’s an important thing to say, and it’s one I’m going to insist upon because, unlike the African Americans or the Asian Americans, we do get white roles. And so that makes it more complicated. Like Wonder Woman was a Latinx actress because she was able to pass. She was just like Danny Thomas.

It makes, in my opinion, it very important to have people, and I’m increasingly doing everything I can to make sure that I have people in my plays. I’ve always committed to giving a platform to people even if they don’t have the experience or the kind of resume that gets hired on the off-Broadway level opportunities. But I do think it’s important to also recognize the complexity of the Arab-American identity, how we’ve been able to pass, how we’ve been passing. And how we insist upon telling our own stories in our own way in a way that also does not demonize, in a self-righteous way, people who are trying, white people or otherwise, to tell our stories, but may not have the student body cast that really wants to be representing. I think it’s a really challenging thing to do with our community. I think it’s easier when it’s Black or white than it is with our community.

Nabra: You’ve brought up so many of the complexities and the different elements that have to be considered when we’re having these conversations about representation. And to dig even deeper into the MENA identity specifically, our region, the MENA and SWANASA region, is huge and incredibly nuanced. And so, I want to go even a step deeper into this conversation and ask you each like how broad or specifically you think we should approach representation in MENA plays?

For example, in Egypt, there are two major ethnic groups; there’s the Egyptians and the Nubians. And even among the different ethnic groups, there are all these different traditions and subcultures. These are things that only really an Egyptian would know: all of the different dialects, all of the different tribes. Even casting a “Egyptian” character implies a certain generality unless the exact place each of their parents and grandparents are from is explained. So, casting anyone as MENA, for instance, as an Egyptian character is already greatly generalizing our cultures. How specific do we get? How do you approach and consider these nuances when it comes to representation, especially in our region?

Tracy: I think it depends on the play and the character and how specific it is. If it’s a really specific play about Nubian culture, you probably want someone who is familiar with that, if you can get it. I think it just depends. If it’s a more broad character or if it’s really specifically about a specific community and it’s helpful to have someone who has that knowledge and history from that community. Again, and as Betty said, sometimes it’s not possible to find someone that’s specific, especially if you’re in a university setting or something like that. But if you’re in a larger theatre and have the resources, if you take the effort to look, you can usually find someone.

But even with me, sometimes I’m offered things, like I was recently approached about workshopping something that was related to Egypt, but it was about a Muslim character. And I had to be real clear, “Yeah, I’m Egyptian American, not Egyptian. And also, my family’s Christian. I’m very familiar with Muslim culture and I’ve grown up around it, but that’s not my personal identity.” I had to be real clear with the folks, who are well-meaning folks, that were just like, “You’re Egyptian, right? Here’s the thing.” And I was like, “That’s cool. Might just be real clear. This is where I’m coming from; this is my background. I am aware of it, but that’s not personally where I come from. Although, I have probably more knowledge about that than someone who wouldn’t be Egyptian would in some regard.” I think, again, depending on the story you’re telling and the nuances, and who’s available, I think the more specific you can get, the better. Because even between countries and regions and even within countries, like Egypt, especially, it’s very complex in terms of religion and where you’re from. For me, it depends on the play and what your goals are. Betty, what do you think?

Betty: I think it’s so important, Tracy, the work that you guys are doing.

Tracy: Thanks, Betty.

Betty: I call you guys the young guns because you’re like five minutes younger than me. Just kidding. Even just the Maia directors, and the work that you guys are doing through that, I deeply, deeply admire what you’re doing for our community. It’s really, really important that someone does that work and insists upon advocating at places where there are resources. I think it’s incredibly and cannot be—and that’s what I was alluding to, the different heights in the American theatre and taking over and taking control and making space for our voices and insisting upon authenticity in a way that I did not think was possible in our community. I just really feel that this is an exciting moment. A lot of it is with much thanks to those young directors who are now in positions of power at different places who are making choices and insisting upon authenticity in a really, really exciting way.

Nabra: I love that you’ve brought up a lot of different elements of this complexity and also the importance of centering the storytelling: What is the story we’re trying to tell? What are all of the elements of representation? How do we hold that all within that process? So many different organizations like Maia directors, like MENATMA, are helping so much with supporting different organizations, different theaters, different groups in making informed decisions.

But that also brings up something both of you have brought up before, which is the importance of creative team members. That having somebody that has some type of cultural touchpoint into these stories will immediately serve as this kind of nuanced advisor in the process. You brought up, Tracy, in a certain play, it might be that, if you’re deeply diving into Islam, it might be even more important to have Muslim representation than it would be or other types of representation within the story. But that’s the type of thing that you as an Egyptian person can bring into that space and help to steer in the right direction. And, of course, the playwright plays such an integral role in that. I’m seeing a lot of, especially notes at the beginning of plays that are a lot more robust that outline how to approach representation for this particular story.

I would love for us to talk more about the creative team as a whole because that’s a space where there’s so much possibility for different types of representation. How do you all think about the benefit of having MENA creative team members, not just as directors, playwrights, but also even the lighting and scenic design, costume design; what is the tangible benefit to that? How have you seen that play out in the processes that you have been a part of from the inception of a play to its closing night?

Betty: Well, I can just attest to, during The Black Eyed, we had a wonderful sound designer, and he got there and did a great job, but there was no Arabic music. There was no Arabic sound in the play initially. That was something I had a hard time articulating what was, I felt, the issue at hand. The sound designer was in there. He was underscoring. I realized I have a problem with sound design in general. I’d flip out because I’ve had a lot of experiences where sound design overpowers the language, and I’m just like, “Wait, wait, stop! I spent a lot of time writing that.” And if you’ve got the wrong sound design... I get triggered by sound when.

I don’t think it’s like film in which you need to underscore things. I did not understand that the issue that I was having in that production was not directorial; it was design. And so, it took me a long time and a lot of a passage to understand that this director who had directed me personally in my play of monologues, Chocolate and Heat, meet with another Arab actor and really understood kind of my entire impulses as an artist. I didn’t understand what was the issue, and the issue at hand was design. As soon as we fixed that one little thing, which is, “This is an Islamic world, and this is an Islamic heaven. We can’t have coral chanting from the Appalachians. We can’t do that. We got to do something different.” Then everything fell into place with that production. I think I was a young enough playwright, and I didn’t understand the elements of what sound does, but if you have Appalachian Christian coral chanting as part of this portal into this different afterlife, I didn’t understand what was triggering me.

Now, as an older player, then we just go, “Okay, we need to get either somebody who’s an Arab musicologist to work with this guy or we need to find an Arab-American sound designer.” Now we’re in a situation where we’ve got spreadsheets of people who are of Middle Eastern descent in every category of design. That wasn’t the case, and even if it was the case, I don’t think I would have the muscle as a playwright to come in and demand authenticity with people that they weren’t working with. Now I do, and the environment is different. But at the time, I did not feel that was the case. But that was one instance, where I could not locate what was wrong with how the production was developing. As soon as we fixed that problem, everything else, in my opinion, fell beautifully into place.

Tracy: As a director, working with the design team, I feel like if I am working on a play that’s Arab-American characters or Arab characters, having designers, at least a couple designers, that are from that background gives you a shorthand. Because I feel like when you have designers or a creative team that has no awareness of culture at all, I end up being like a teacher in the room. I just feel… Honestly, it wastes time because you have to go through and explain why this is like this. And then, “Here’s some history,” and then you have to kind of also be this dramaturge.

There's uncomfortability about it that you can’t just relax, like, “Oh yeah, here’s that quick shorthand,” Like, you and I can talk about things, Nabra, in Egypt. For me, Betty, sound is not a thing I’ve had a huge problem with. Costume design is my pet peeve. For somehow, I don’t know why with costume centers, especially, there’s this veering towards stereotypes that’s real hard to pull back from. I remember working at place, and it’s like there might be Arab characters but modern world. And they’re like, “We have to add this textured, Middle Easterny ster—” and I’m like, “No! They’re just people. They don’t need to wear tribal clothing. Nobody wears that. That’s not a thing.” And then, feeling like I’m just screaming in my head all the time. This has happened many times to me. I don’t know why there’s always that veering there, like, “We have to make it look ethnic or cultural,” even if that’s not part of the world or the play at all. That’s annoying.

Betty: Yeah. That’s an element I can look at a design and go, “Hell, no!” Whereas, with sound, underscoring your language and entering portals in different worlds, going from living to afterlife sounds, for me, that was much more challenging. And the other thing is, I'm working on a novel right now, it’s about a theatre director. Also, in Middle Eastern, you’ll have a song that sounds like Yankee doodle to an Arab audience. Like, “Cue New York,” and they play “Yankee Doodle...” That’s an essentially American song, and that’s how obtuse I feel like the sound design is when it comes to the Middle East. It’s like, “Oh my God, now we’re playing, Fayrouz.”

Tracy: Yeah. They’ll find the most stereotype music possible.

Betty: Exactly. Arab audience is like listening to Yankee Doodle to represent, “We’re switching to New York now.” It’s interesting. For me, finding real sound designers who can underscore and play with, for me, it’s a balancing act. I got in theatre to play. I got in theatre to work with people who I vibe with and love, and they the same.

Just in the way that I've been embraced by African—I’m at a predominantly African American theatre company as their playwright in residence. That is very much part of my history. And so, for me, again, I have an ethos where it’s really important for me to feel connected to other people of color, particularly, those who have an activist net.

The Arab world is very politically diverse too. I want to be in the room with people who are on the same page with me about what it means to do plays that challenge the status quo and the narrative of power. That is to me very important and something I insist upon. We have to, as people of color, continue to complicate the conversation about, “What are the politics of these people? What are the politics of these people doing this play by this writer in this environment? What plays are you not doing instead of this play?” You know what I mean? “What does that mean? Why?”

I have always said, and I’ll say it a thousand times, if I wrote an honor killing play, I feel like that would be my most produced play if I wrote a play that just reinforced stereotypes. I just think I’m constitutionally unable to do that. Even though, I will say, when I went to Palestine in, I think, 2006, a Christian girl from my village, which was remote, and now it’s a big city. But when the my parents lived there it was a village, was killed by her father for running off with a Muslim. That was my “welcome home to your village.”

I have stories in me that I need to tell. Just like Alice Walker had stories of Black men being brutal to Black women that she needed to tell. One of the things in this idea of representation is I think I have overly taken up the mantle of “I have to represent well.” I was lucky enough to work with Marina on my last play, and one of the things I did was play with those stereotypes of me always trying to present Arabs in the light of, “We’re sophisticated. We’re cool. We’re educated. We’re fantastic. We’re fun and fabulous,” by making the granddaughter of this very sophisticated professor who speaks seven languages and has two PhDs, like a bumpkin who didn’t understand the difference between Bali and Bollywood to play with this idea of, “This is not the full Arab-American community. We’re just as goofy and ignorant as a lot of people.”

I was able to put both the representation of an Arab-American that I’ve been trying to do my entire career, which is, “Look at how sophisticated we are. Look how cool we are. Please don’t kill us.” If you grow up in an American environment and you’re not particularly a student and all you do is watch the Kardashians, this is what you get. Whether or not you're Arab-American or Indian American, or African American, this is who you are. But I feel like one of my struggles is I’ve so carried the burden of representation that I sometimes censor myself when it comes to writing about women. I have, up to a certain point in my life, felt being Palestinian-American was the most difficult thing about my identity.

But as I age and as I see how American theatre treats its mid-age women, I think being a woman may be the more difficult identity to carry as one tries to be a mid-career, or a master playwright, or even a director. I do not think I have worked with some of the best and most celebrated directors in American theater. And the women are not in the same stratosphere as the men. Not in the same stratosphere. That is entirely a function of people being hired because they look like people who have been hired before. That’s something that I’m grappling with.

Representation to me is not just who I put in place. It’s, “Do I have the courage to really tackle those stories? Really go into what it feels like to be a Christian girl to a village that was entirely Christian and see what is my cultural counterpart which is a Christian girl, who never left, being murdered for marrying outside of her religious community?” What so challenging for me was her father was let out of jail by probably predominantly Muslim men. It's like she ran off and converted, which is ridiculous because the Christian men get visas, and there’s not a lot of them. You either just wait around for somebody to date you or you look elsewhere. It was heartbreaking for me, and I do want to write about it. But do I want to in American theatre tell that story right here, right now? If the issue of representation was not so on the forefront of my mind, I might.

Nabra: Well, that’s what one of the tragedies of the consequences of lack of representation is we get less stories, we get less nuanced stories because we’re so careful about how we’re telling these stories, and which stories are going out there. We also lose time, we lose resources. As Tracy pointed out, if we have proper representation within creative teams, we don’t have to educate. We can make higher caliber art because we get that time back, which is such an important resource. It’s literally the way we tell our stories and what stories we are able to tell are actively being influenced by the status of representation of different MENA communities in the United States. There are really tangible consequences that you both have beautifully outlined.

Marina: And on the creative team front, it was so interesting to hear because the idea of the shorthand is so wonderful, right? That’s what we love in theatre is when we can create that shorthand. I recently talked to Palestinian author, Shereen Malherbe, I believe, is her last name. And she talked about how she’s rewriting, she’s making Jane Eyre and remaking it. I said, “Okay, that’s interesting. Why?” She said, “Well, Jane Eyre is steeped in Christian theology. And I want to see what this story is like when it’s steeped in Islamic theology.” I had never considered, one, Jane Eyre to be steeped in Christian theology, but, of course, it makes sense. But that’s the rehearsal room in the instances that you’re talking about are steeped in something more when we don’t have to teach people about a culture, or we don’t have to use Yankee doodle as a stereotypical thing. There’s something more that’s happening because it’s the world that is actually being developed, which is what we do. We create new worlds on stage. Just thank you for bringing so many thought-provoking points to the forefront.

I know we don’t have a lot of time left, but I have two questions that are on my mind, just generally, which is… The first is about in new play development processes, which you’ve both have been part of, if there’s a way that... Sometimes you get feedback that is really not useful if it’s coming from a group that is outside of the group of creatives that are making that piece. I’ve been in feedback processes where white audience members have often had unhelpful things to say in regards to representation, and that’s putting it, I think, mildly. But also, if you have a story that you want to share around representation that we just haven’t covered yet, if it’s positive or negative as specific or not as you want. But those are the two things that are left on my mind as we’re wrapping up our conversation today.

Betty: Well, as it playwright, I don’t know what to think about feedback. On one level, you’re getting feedback every minute of the day because you’re getting actors like, “This line doesn’t make sense. Can you change this? Can you do this? Can you— What? What?” With As Soon As Impossible, we updated it. I wrote fourteen years ago. It was 2007 in New York; both wars were happening in Afghanistan and Iraq. That was it. We were in it. And now, it feels like, especially to do at a Stanford thing where the kids are probably not cognizant fourteen years ago due to, you know, the culture. So we had to update it and make it in the time of the Muslim ban. That was challenging, and that was based on feedback. And so, I’m somebody who always is like, “No, you’re wrong! No, this is my work!” And then I go home and I’m like, “No, they’re right.”

I think that part of the creative process is knowing who you’re dealing with. And if you know that the person gets defensive and protective and freaks out and is going to calm down the next day, you can give them that time and space to do that. But I think the feedback within the rehearsal room is probably much more challenging for me than the feedback... The other thing is we did a wonderful reading of As Soon As Impossible with Samer right before we did the Stanford production directing. He really did one of the best Zoom readings I’ve seen because he put the set on and he created this thing where the people popped up where they might be in the set, which I had never seen with a Zoom reading, and I thought it was brilliant.

So, we got feedback from the subscribers of Theater Works. I kid you not, we got a hundred letters. They were glowing, loving, “This should be on Broadway,” “Best play I've seen at this place, and I've been a subscriber for forty years,” stuff like that. My mom wrote them all, and I got one person who said, “I found the main character, the girl, so off putting, I turned her off.” And that’s the only thing I remember from the hundreds of things that I physically have to look through. The only thing I remember is some guy not being able to hear an Arab-American woman be unlikable and be human and be flawed and do terrible things and laugh at herself and laugh at them and inch towards growth but not really get there. I said, “Wow!” As a writer, I’m trying to get that one guy to keep his TV on or his Zoom on. That’s my job. I can have a coterie of Palestinian-American women who really love my work, but I’m trying to reach that one guy who turned off his thing. I think that that’s one of the things about representation that’s interesting. I’m not sure if it’s just a function of being an artist and sensitive or it’s something particular to being a person of color or a woman that you want every single person to like it and to at least listen.

Tracy: I think feedback around new play development, I’m real careful and cautious about the process for receiving that feedback and who we’re getting that feedback from. It also depends on the playwright and what their intentions are. I’ve had playwrights that are like, “I don’t want any feedback. I just want to hear reactions from an audience,” or we might get really specific feedback from like some invited dramaturges that we know really well.

When I do do feedback for a new play workshop, I try to use like Liz Lerman-type methodology, where it’s very, very, very structured. And if something is unhelpful, we can avoid it or shut it down real quick to make sure that we aren't getting those helpful meaning, but not helpful suggestions or questions from folks in the process.

Nabra: Thank you both. I know that we are at our time and we’re so grateful for hearing you both speak about your experiences today and just really diving into it. I know that you got into some nuanced nitty gritty things that I think can be tricky to talk about, but we’re so grateful to have you with us today.

Marina: Thank you so much. You’ve uncovered so much, and there’s so much deeper to go. You couldn’t see all the head nods as you were listening to this podcast, but there’s so, so much behind what you each have touched on today. Thank you so much.

Thank you so much for having tea with us. This has been another episode of Kunafa and Shay. We're your hosts, Marina and Nabra. This podcast is produced as a contribution to HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of this series and other HowlRound podcasts in our feed on iTunes, Google Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you find podcasts.

Be sure to search HowlRound Theatre Commons podcasts and subscribe to receive new episodes. If you loved this podcast, post a rating and write a review on those platforms. This helps other people find us. You can also find a transcript for this episode, along with a lot of progressive and disruptive content, on howlround.com

Nabra: Have an idea for an exciting podcast, essay, or TV event the theatre community needs to hear? Visit howlround.com and submit your ideas to the commons.

Marina: We hope you tune in next time. Thanks for joining us on Kunafa and Shay.

Marine and Nabra: Yalla, bye!

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here