Knowledge Spaces

While working on stage productions, we have the possibility of using the museum’s collection of puppets, mobile stages, sets and props, text and directors’ books, scene photos and posters, programs, and playbills for insight into other or older puppetry play forms. Vice versa, our puppeteer’s gaze at the artifacts broadens our knowledge about the collection, which consists of approximately twenty thousand heterogeneous artifacts from Europe, Asia, and Africa. We understand the collection as a large knowledge space that is always in motion and that should be available to the general public. An important goal for the future is to make the collection, including the archive and the specialized library, available to research users worldwide, creating a digital research infrastructure that contributes to a transcultural, interdisciplinary exchange of puppetry knowledge.

The small marionettes effortlessly contrast their precise delicacy with the large figure, and the small theatre world contrasts with Shakespeare’s force of language and subjects.

Little to nothing is known about the puppets of non-European origin. In the form of the virtual exhibition “Colonialism and Puppetry – Untangling the Strings” last year, we tried to trace the path of non-European artifacts from the performative puppet to museum object. The exhibition was the beginning of a postcolonial perspective on our collection and offered us possibilities to deal creatively with the “empty spaces” around the collection objects. Instead of asserting from an institutional point of view ethnological or theatre historical contexts of the objects, we invite visitors to offer their knowledge and/or associations. To our current project, “Who’s Talking? Change of Perspective on Provenance,” we invited international and diverse expertise to approach questions of original performative contexts and of (post-)coloniality, racism, and appropriation through artistic research. We are developing working methods here, and although the results of the project are not yet finished, we are hoping to integrate them into our opening exhibition.

There is one loss that all our objects have suffered: that of the performative. The collection items are always only “traces” of scenic practice. How can these traces now be read, researched, and documented? How can cultural contexts be taken into account in addition to the performative ones so that the polyphonic and multilayered spaces of knowledge that surround the objects remain (or can be expanded)? These questions will continue to occupy our work in the future.

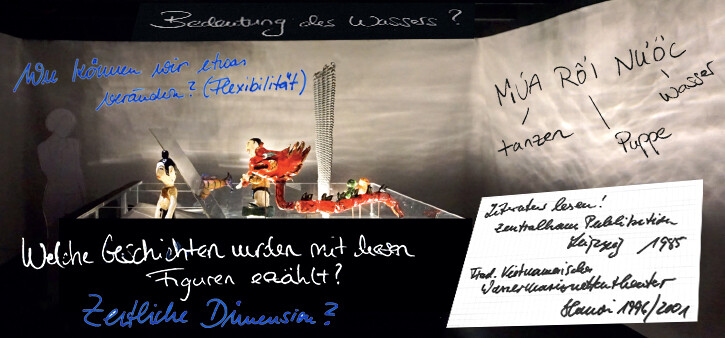

Exhibition Spaces

The spaces that are created in our exhibitions are another dimension of spaces of puppetry. They have different parameters: neither the performance nor the play determines them—the exhibition and its visitors do. The parameter of time also takes on a different role. While puppet theatre performances exist solely in the present, there are temporal dimensions in exhibition spaces, because even with historical (especially non-European) exhibits, past and present are considered at the same time.

We can make use of the fact that, at the Thinking Lab, there are both active puppeteers and exhibition practitioners: together, we can make puppetry theatre fruitful for exhibitions. We want to illuminate a wide variety of puppet theatre forms and the artifacts in our collection from different perspectives, and our collection of objects forces us to readjust these perspectives. Who is talking about the objects? Are we letting them talk? What stories are they telling?

As an interdisciplinary group, connecting to puppet theatre practice opens a whole new set of possibilities for taking on these perspectives: puppetry as a performative art that can effortlessly transcend boundaries and limitations of the human body, and that can vividly capture multiple perspectives and ambivalences in images by means of the puppet. This is an art form where many answers to questions of the day—racism, equality, decolonization of institutions—can be visualized and set rolling.

Everything influences how the performative space develops—even the audience and their reactions and backgrounds.

Our wish is that museums become more like theatres. Interpretations are subjective, fragile, mobile; exhibitions, like productions, should be understood as offers of interpretation and only excerpts from the multitude of possibilities. Puppetry in its European tradition left behind its fixed stage forms of the puppet booth and marionette stage with hidden puppeteers decades ago, aiming instead for the empty theatre space that is filled according to dramaturgical decisions: the story, the characters, and their demeanor, temperament, and gestures.

Everything influences how the performative space develops—even the audience and their reactions and backgrounds. An equivalent on the side of museum practice would mean to refrain from the fixed master narrative and, rather, to see exhibitions as interpretations, offers, and proposals to the audience, who are invited to participate. We must continuously explore and work on themes by a frequent and constant rotation of questions, to dispense with showcases as the only form of presentation and permanent exhibitions, to acknowledge the bodily dimension of the puppeteer as well as of the puppet in relation to the audience’s body. For our exhibition spaces, for example, we will consider different modes. What mode do we give a space: stormy, overwhelming, or even for once gentle?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here