Alabama/African American/American History

February invites a time to celebrate and consider the history of African Americans. It also attracts an interrogation of our American narrative, and a critique of educated America’s complacency with regional complexity and the romanticization of trauma.

“I wish Black History Month wasn’t relegated to a month,” said Rick Dildine, artistic director of ASF. “That’s something I’m personally interested in—that we don’t compartmentalize moments. Black history is American history; they run alongside each other. They are interwoven.”

At the heart of Four Little Girls, which focuses on the next generation of Alabamians telling the story of their ancestor’s past to the state elders themselves, is a critique of America’s immature, assumptive approach to understanding Alabama where, in the nation’s imagination, tragedy outweighs triumph, problems overwhelm potential, and cheap-and-loud stories of white noise have more currency than humble-and-rich stories of black courage and brilliance.

Reflecting on the play, Lisa McNair, the sister of one of the little girls, said: “My education had been denied of the goodness and strength of my people,” then added: “This is American history.”

Ham, whose mother was a member of the 16th Street Baptist Church—the site of the bombing—wrote the play with the aim to humanize Alabama’s civil rights history, “reminding people of [the victims’] names since they’re only referred to as the ‘four little girls,’” she said.

There is a tendency to demean Alabama’s presence in transatlantic history. Our Americana instincts tell us that Boston is where the against-all-odds American revolutions happen, not Montgomery. It’s a convenient simplification of regional identities, reckless in its erasure of African American figures. Considering the brave contributions of civil rights footsoldiers, “all of us are black history,” said Alabama’s Democratic Congresswoman Terri Sewell in a public conversation reflecting about the play.

There is a wide-eyed awakening happening at the regional theatre rooted in the space that saw the rise of the confederacy and the civil rights movement.

Montgomery Public Schools

“I think theatre is local,” said Dildine. “Once an audience feels like they’ve learned the rules, that’s the moment you change them.” According to him, the rules Alabama Shakespeare Festival had set up over its forty-year history were those of majority male and majority white stories, produced by artists who did not live in the state and who had no connection to the land, the people, and the culture. “That’s been the given,” he says. Now in his second season, Dildine has set out to revolutionize that institutional legacy through intentional, humbled listening.

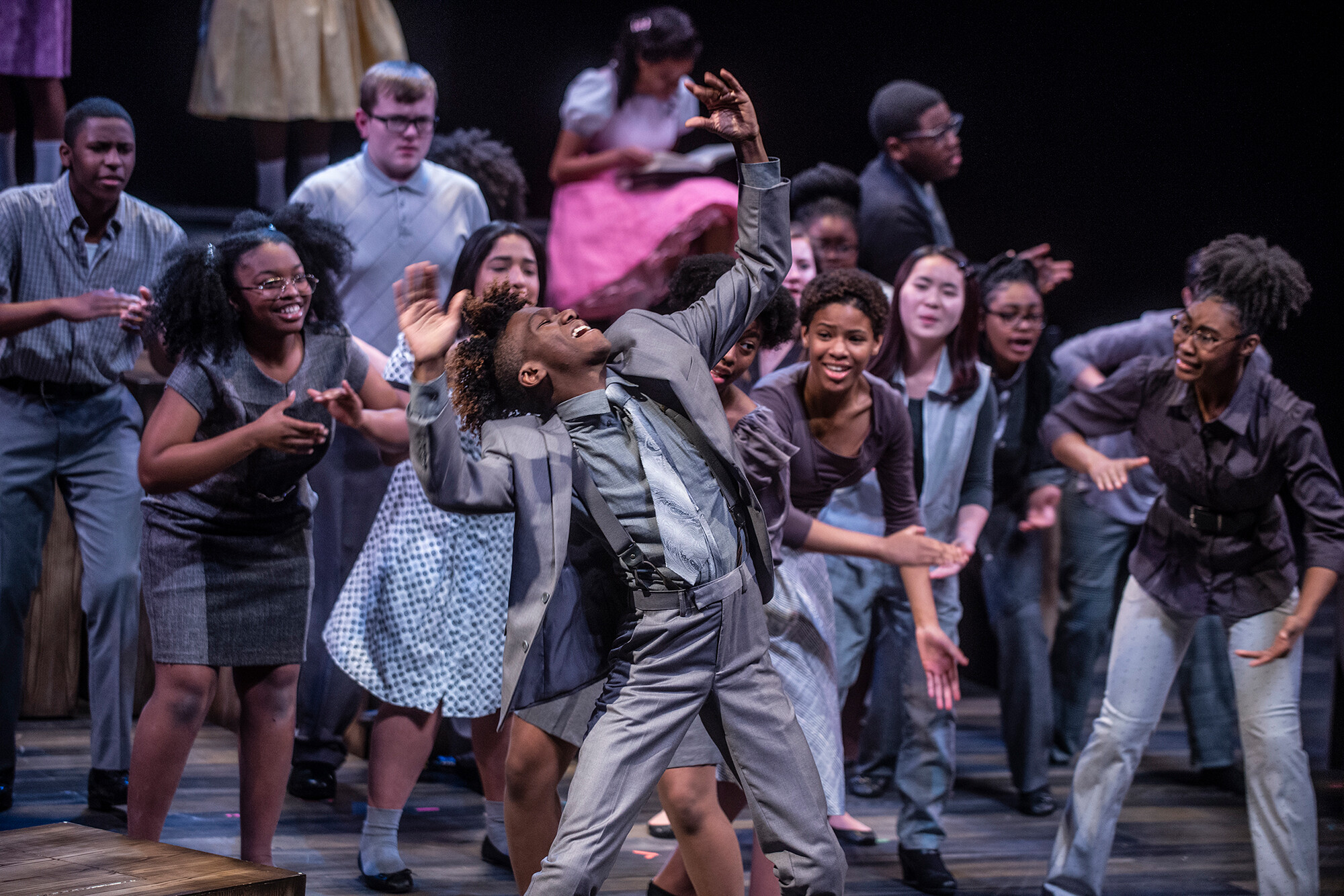

To envision the lifeforces of Cynthia, Addie Mae, Carole, and Denise for Four Little Girls, the Alabama Shakespeare Festival exclusively enlisted the young people of Montgomery Public Schools—a school district where 78 percent of who are African American, 9 percent who are white, and 4 percent who are Hispanic—to animate the history. This was a bold move for a theatre redefining its relevance and a school system in crisis. (Since 2017, Montgomery Public Schools have been going through a turbulent state takeover.)

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here