Theatre History Podcast #48

Learning About Kutiyattam with Dr. Erin Mee

How can a play whose script covers less than ten pages take weeks to perform? That’s just one of the many questions we delve into when we explore the world of kutiyattam, which is a particular way of performing Sanskrit drama in the southern Indian region of Kerala. Dr. Erin Mee of New York University introduces us to this fascinating art form, which keeps bringing classical Sanskrit plays back to life thousands of years after they were first performed. This is the first of a two-part series on theatre in India: join us next week, when Erin leads us on an exploration of how Indian theatre has developed in the decades since independence.

Links:

- Watch Erin give a lecture on kutiyattam in this video from the Asia Society.

- Learn about the technique and training behind a kutiyattam performance in these videos, in which demonstrate eye and face exercises, the 9 rasas, and mudras.

- See a 2012 performance of The Abandonment of Sita, performed by Natanakairali.

- Watch additional footage of kutiyattam performers here.

- Visit UNESCO’s website on kutiyattam.

- Learn more about Erin and her work.

If you’re interested in learning more about kutiyattam and ancient Sanskrit drama in general, here are some reading suggestions:

- Scholarly studies:

- Plays and original texts:

You can subscribe to this series via Apple iTunes, Google Play Music, or RSS Feed or just click on the link below to listen:

Transcript:

Michael Lueger: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a knowledge commons by and for the theatre community. It's available on iTunes and HowlRound.com.

Hi. Welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Mike Lueger. The subcontinent of India is home to a dizzying array of cultures, many of which have rich theatrical traditions that go back hundreds or even thousands of years. Today we're going to discuss just a few of those traditions. And we're gonna do something a little different from what we normally do.

This is part one of a two-part conversation on the history of theatre in India. Today's episode will be an overview of Sanskrit drama, in particular the performance form known as kutiyattam. Next week we'll look at modern Indian theatre.

Our guests for these two episodes is Dr. Erin Mee. She's an assistant Arts professor at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts and the author of Theatre of Roots: Redirecting the Modern Indian Stage. She's also a stage director and the founding co-artistic director of This is Not a Theatre Company. Erin, thank you so much for joining us.

Erin Mee: Well, thank you.

Michael: Let's begin with some terminology. What do we mean when we say Sanskrit drama?

Erin: When people refer to Sanskrit drama, they're usually referring to the plays of Shudraka, Bhasa, Kalidasa, plays that include The Little Clay Cart, Shakuntalam, Urubhangam, Karnabharam, Bhagavadajjukam, Svapnavasavadattam, and a number of others.

Sanskrit drama originated between 200 BCE and 200 CE, when traditions of music and dance were combined with a type of recitation used in religious rituals. The aesthetic treatise called the Natya Shastra, which is attributed the sage Bharata, tells a wonderful story about Sanskrit drama in its early years. It's a creation myth that at a time when people were greedy and argumentative, the gods created drama to entertain them and give them something to do, but to educate them as well.

The demons broke up a particular performance, and the gods felt that drama was so important that they built a structure to protect it, known as a theatre. From the very beginning, Sanskrit drama has always been multidisciplinary, multimedia. It's always had aspirations to educate people as well as to entertain them, and it's always included dance and music.

In 1912, thirteen plays by the playwright Bhasa were discovered in the southwestern state of Kerala and these plays scholars discovered were being performed in a genre known as kutiyattam. Kutiyattam is a particular way of performing Sanskrit drama in the state of Kerala. Kutiyattam then, although it has changed radically over the last 2000 years, gives us some idea of how Sanskrit drama might have been performed. With classical Greek tragedy, we have only texts. With Sanskrit drama, we have a performance genre that tells us something about how Sanskrit drama might have been performed.

Bhasa's play Urubhangam is in its English translation about eight pages long. In New York City, an eight-page play would be part of a ten-minute play festival, but when this is performed in the kutiyattam repertoire, Bhasa's play takes about forty-one nights to perform. Plays in the kutiyattam repertoire are based on stories from the Mahabharata, the Ramayana, and other familiar sources, so most spectators already know the story going in.

Kutiyattam then is not about telling the story. It focuses on how the performer interprets the text and embodies the narrative. It's not unlike jazz. You don't go to a jazz concert to hear someone play the melody. You don't go to a production of Hamlet to find out what happens at the end. A kutiyattam performance doesn't present the play, but elaborates on it, and each play can take five to forty-one nights to complete.

Each scene within the play has its own title and is meant to be performed as its own entity. Then within each scene, a performer can spend up to three hours illuminating three lines of text by making political and social analogies, exploring emotional associations, and telling related or background stories.

On the first night of a kutiyattam performance, the main character will come out and give his backstory to the play. He'll talk about his own personal history leading up to the moment the play begins. He might tell the story that's told in the play from the perspective of his character. This might take several nights, depending on the character, so the character might come back on night two and night three. If not, then on the second night, the second character will come out and tell the story from his character's perspective, give background information about his own character and perhaps tell other, related stories. On the third night, another character will come out. On the fourth night, another character will come out, etc.

The equivalent for something like Oedipus Rex would mean that Oedipus comes out on the first night and tells the background to the story. He talks about growing up. He might tell the story of when he was taken out to the shepherd, etc. etc. Jocasta might come out on the second night and tell the story from her point of view, tell other background and related stories. The shepherd might come out and talk about how he raised Oedipus. Antigone might come out and talk about what it was like to grow up in this family. By the time you get to "the play," or what we think of as the play, you've explored all of the background and related stories. You've really had an in-depth exploration of character. It's almost like doing dramaturgical research with the audience as part of the play.

And then the vidushaka comes in. The vidushaka is the clown figure. His job is to translate the Sanskrit text of the play into Malayalam, which is the language spoken in Kerala, and to make political and social analogies between events in the play and events in the real world. One of the famous stories told about a vidushaka is that there was a judge in the courts of Kerala who kept falling asleep while people were giving testimony, and then he would wake up and give his ruling. He went one night to see a kutiyattam performance, and the vidushaka made fun of him and said, "Oh, this character in the play is like that judge who never listens to any of the testimony, but then he wakes up and just gives his ruling on the case without actually having heard any of the information. The rumor is that the judge never slept through another court case again.

Now, this may or may not be true, but what it tells you is the role of the vidushaka in society. His role is to make the play relevant to the audience. In this way, in these forty nights leading up to the final night, the story is told and retold from many points of view. The background to the story is fully explored, and the story is made relevant to the audience. This process is known as nirvahanam. On the final night of kutiyattam, what I grew up thinking of as "the play", is performed.

The play, the text without elaboration, is only a tiny fraction of the total experience. Spectators don't follow a linear plot across time. They explore each moment at many levels and in many modes. They have a sort of series of vertical experiences rather than a horizontal experience.

The nirvahanam, the elaboration, the interpretation, is the responsible of the performers. They improvise physically on the text during performance, and these improvisations are based on guidelines set out in the attaprakaras or acting manuals that are passed down from teacher to student during training. Because the elaborations actually take precedence over the text, the acting manuals are even more important to the performers than the text of the play. The acting manual, the attaprakaram, prescribes the ways in which each actor should perform his part and the important parts that he has to remember while acting his part. It also details the gestures to be used, and it discusses the various modes of acting, the denoted sense, the connoted sense, the wordplay, etc.

In fact, the performers in kutiyattam are not interpretive artists, they are creative artists. The idea is that they are not being faithful to the text. They are expected to elaborate, to comment on, to make connections with, to, one might say, remake or adapt the play. These elaborations are done through mudras, which are a way to give physical form to a thought or feeling.

The purpose of all the elaboration is to get out the emotional essence of the performance. The goal of kutiyattam is to create rasa, or to create a rasic experience for the spectator. According to the Natya Shastra, there is no drama without rasa. Rasa has been variously translated as juice, flavor, extract, and essence. In the context of performance theory, it's the aesthetic or emotional flavor or sentiment tasted in and through performance.

Bharata, the putative author of the Natya Shastra, tells us that when foods and spices are mixed together in different ways, they create different tastes. Similarly, the mixing of different basic emotions arising from different situations, when expressed through the performer, gives rise to an emotional experience or taste in the spectator, which is rasa.

Michael: Erin, I'm really curious. What is it like to be an audience member at one of these performances, given that they might go as long as forty-one nights?

Erin: Well, truthfully, I think in this day and age, the only people who are at all forty-one nights of the kutiyattam performance are PhD scholars writing their dissertations, to be completely honest, and other kutiyattam performers who are learning and studying kutiyattam from the masters, etc. etc. But it's really incredible. You get this incredibly detailed exegesis, if you will, on each part of the play, and Michael, I think for our podcast listeners, let me make an analogy that may or may not be useful.

If you have seen the Oresteia, you know that it begins with Agamemnon. In Agamemnon, there's a long kind of laundry list from the warriors returning from war, and they say, "We went from here, to here, to here, to here, to Aulis, to here, to here, to here." When they say "Aulis", if you know the story of Iphigenia in Aulis, or if you saw Ariane Mnouchkine's production, by the time you see Agamemnon, you've spent three hours the day before seeing Iphigenia in Aulis, which is the story of a father sacrificing his daughter to be able to go off to war, then that one word really punches you in the stomach. You get a real hit of emotion.

The experience of the spectator in kutiyattam is not one of following a linear plot. It's not a horizontal experience across a plot line. It's a series of vertical experiences. You explore each aspect of the play so fully that by the time you get to "the play" on the forty-first night, each reference carries with it a wealth of emotional experience, so that the word "Aulis" make you think, "Oh, right. That's where the father sacrificed his daughter, killed his own daughter."

The experience then of seeing kutiyattam on any of these first forty nights is the experience of seeing an incredible performer delve into particular moments in an extraordinarily rich way to bring associations and other stories, related stories. It's a way of going so deeply into the material and resurfacing. The experience of seeing a kutiyattam performance then is the experience of taking particular moments and taking the time to delve deeply into them and explore each moment in its richness with an entire set of associations that are political, social, emotional.

You bring that set of associations and depth to your experience of "the final play" on the forty-first night, which means that each time anything is mentioned in the final performance, you refer back to the three hours that you spent exploring that reference in great depth and detail. It might be like reading a paragraph with forty footnotes, and each night is an exploration of one of those footnotes, which is, in and of itself, a twenty-page paper. Then on the final night of performance, if you read the paragraph, you bring to it your experience of each of those footnotes.

Michael: For the audience, their bringing all these different associations built up over a number of different nights of performance, but if you're a performer in kutiyattam, how do you go from and eight-page script to this long, elaborate performance? What are you working off of?

Erin: Well, the responsibility for this thorough interpretation and elaboration is handed over to the performers, in fact. These elaborations are physical improvisations on the text, and these are based on guidelines set out in what are called attaprakaras, or acting manuals, and these are passed down from teacher to student during training. And in fact, because the elaborations take precedence over the text, the acting manuals are even more important to the performers than the text of the play. The attaprakaram prescribes the ways in which each actor should perform in his part and the important parts that he has to remember while performing. Details, the gestures to be used. It discussed the various modes of acting, the denotative sense of a line, the connotative sense of a line, the wordplay, etc.

Remember, I'm gonna talk about kutiyattam training in a moment, but the knowledge that these performers have is given to them through training which lasts for seven years, and they train for about eight hours a day six days a week for seven years. By the time they're performing, by the time they're actually improvising, the basis for the improvisation is deeply embedded in their bodies.

Michael: This buildup of associations leading up to the performance of the "final play" sounds like there's something a little bit cathartic about that, but that's not how this form of theatre works. Am I correct about that?

Erin: Yes. The question then is "What is the purpose of all of this elaboration?" The goal of Sanskrit drama, the goal of kutiyattam, is to create rasa. The Sanskrit term "rasa" has been translated as juice, flavor, extract, and essence. In the context of performance theory, it's defined as the aesthetic flavor or sentiment that is tasted in and through performance. The Natya Shastra notes that when food and spices are mixed together in different ways, they create different tastes, so similarly, the mixing of different basic emotions arising from different situations, when expressed through the performer, gives rise to or brings out an emotional experience in the spectator, which is rasa.

There's a later tenth century aesthetic theorist, Abhinava Gupta, who describes rasa as an act of relishing. Rasa is active, sensorial, experiential. It's in the body. It exists actually neither in the performer, nor in the partaker, but in their interaction. Rasa positions the audience member as an active participant and partaker, and co-creator of the event, in fact. Rasa is really an act of relishing, so the emotion that is embedded in the text or the situation is extracted by the actor, converted using the actor's imagination into a sort of emotional essence which is then made enjoyable and shared with the audience member, spectator, partaker I would say, who experiences the essence in this new way.

Michael: Now, what about the performers themselves? How do you create this sense of working together with the audience to create this feeling? What is required in terms of training, in terms of performance?

Erin: Kutiyattam performers train for at least seven years before performing publicly. Back in the olden days, the right and the responsibility for performing kutiyattam was handed down in the Chakyar family from father to son, from uncle to son, etc. etc. Often the form of learning, at least at a young age, would be relatively informal. You would sit around while people were working, you would attend performances that your family was performing in, and then as you got older, you would begin to train more formally in music, in acting etc.

Now training happens more formally in institutions such as the Kerala Kalamandalam, where students will begin at about four o’clock in the morning doing eye and face exercises for several hours, and then they'll have breakfast and a bath, and then they will work on hand gestures, mudras. I use this term mudra, it's often been translated as "hand gesture", but it actually is really a full-body gesture. Then lunch and then during the hottest time of day, most people will rest, and then in the evening when it's cooler, students will do leg exercises and study the stories of the plays and the mythology, etc. etc.

Students train for six days a week throughout the entire year, and then after about seven years of formal training, they will begin to perform publicly. The training is very, very intense. One of the reasons that the training is so intense is that the performers do improvise. The training is extremely formal.

There's a phrase that's used to refer to the kind of training that happens in kutiyattam, "Where the hand, there the eye. Where the eye, there the mind. Where the mind, there the emotion. Where the emotion, there the rasa." Performers who are training in kutiyattam first master the outward manifestations. The hand gestures, the body gestures, the eye movements, etc., and this phrase teaches you that if you do those well and execute them mindfully, if for example you are focusing on what you are doing, on your hand gestures, "Where the hand, there the eye," then your mind, your attention, your focus will follow. "Where the eye, there the mind." Where the mind focuses, there the emotion will arise, and where the emotion, there the rasa.

The training embodies a philosophy that we would call outside-in, and in fact, there's a feedback loop between emotion and physicality. We know that if you feel depressed or unhappy or sad, you often slouch, but it is also true that if you slouch, you will feel unhappy, depressed, and sad. There's a feedback loop between physicality and emotion, and the philosophy embedded in kutiyattam training is that if you master the physical manifestation of the emotion, of the scene, of the character, the emotion will arise in you, and then you can share that with the audience.

The kutiyattam performer does not build the character on his or her own personal experiences. In fact, the Sanskrit term for acting is "abhinaya", which literally means "to carry forward". It is the actor's job to carry forward, to present, to share with the audience the character, the emotion, the rasa. Rasa is in fact a shared experience. It exists neither in the performer, nor in the audience member, but in their interactions. The performer's job is to carry forward the performance and share it with the audience member, and in that sharing, in that interaction, rasa will occur.

There's a famous phrase that in order to do that, the performer doesn't have to become the character any more than a glass of wine has to become the wine to deliver the wine to the lips of the taster. Again, if we're using tasting and ingesting as the central metaphor, the performer is what's also referred to as the katapatram, the vessel that carries the story forward and shares it with the partaker. The performer really learns from the outside in, but of course, the performer is their own first audience member in the sense that if they are paying attention to what they are doing, their performance will evoke emotion in themselves as well as in the audience member, and that's how the performance becomes full and rich and dynamic.

I took some videos of one of the most amazing kutiyattam performers demonstrating eye exercises, face exercises, mudras, and the navarasas. When I was in Kerala in 1993... I've posted those on Vimeo, and Mike it would be wonderful if you would be able to at the end of this podcast give links to those videos so that anyone who's listening to the podcast can really see how this training works.

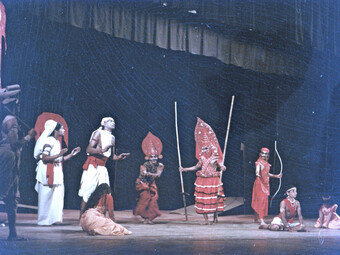

Michael: Now, Erin, what is a kutiyattam performer wearing during one of these performances?

Erin: Sanskrit drama doesn't hold up a mirror to life. Most of the characters are gods, heroes, or demons, so the costuming in kutiyattam is designed to look other-worldly. The costumes show character type rather than individual characteristics. Individuality is in the acting and not in the costuming. The make-up reflects the moral characteristics of the character, so the more distorted the make-up of the character, the more distorted, the moral characteristics are of the characters.

If you look at the video clips that Michael will post to the end of the podcast, you will see there are things that look like little ping pong balls on the face of some of the characters. If you look at the profile then, those white blobs distort the profile of the character. In the same way that the character is physically distorted on the outside, that's an outward manifestation of the moral distortion of the character on the inside. The costumes really are meant to tell you about the moral characteristics of the character rather than the psychological motivations or characteristics.

Michael: Erin, I have to make a confession here. As someone who's taught my fair share of theatre survey and theatre introduction courses, I'm always a little bit at a loss as to how to frame and teach a play like Kalidasa's Shakuntala. Can you tell us a little bit about how these ancient Sanskrit plays are different from what we might expect from an Ancient Greek drama or from a modern Western drama?

Erin: Shakuntala is a beautiful play. To be honest Michael, I always assign the plays of Bhasa to my students because I can then connect Bhasa quite directly to kutiyattam so that they then have some idea of how Bhasa's plays might have been performed. My students always have their minds blown when I tell them that this eight-page play that they read would take forty-one nights to perform, and I think that's one of the biggest differences, is that Sanskrit drama from what we know would not have been playwright-initiated, text-based, plot driven. The elaborations would really... The nirvahanam is what would be the focus of performance.

I think it's difficult to read Shakuntala and imagine how that might be performed over forty-one nights. I think one thing or more, given the fact that it's a longer play, that we need to remember about Shakuntala, about all of these Sanskrit dramas, is that the goal is not to create a cathartic experience but a basic experience. If cartharsis is about the purging of excess emotion, A leads to B leads to C leads to D leads to E leads to a cathartic moment and a denouement, because the ancient Greeks believed that moderation was the goal, that too much emotion was not healthy.

Catharsis was designed to purge excess emotion. In order to reach that climactic moment, you need a linear structure that builds, where the tension builds and the tension builds and the tension builds. You need to go from A to B to C to D to E, and in moving from A to E, tension has to continue to build until finally you reach a climactic moment, and there is a release of excess emotion. Then you wrap everything up and people go home.

Rasa is about savoring emotion. It's about relishing emotion, so it's fundamentally a different approach to an idea about emotion, which is that emotion is not something that needs purging. It's something that needs to be relished. These Sanskrit dramas are about generating, wallowing in, relishing, experiencing emotion, and to do that, you need a dramaturgical structure that allows you to go deep into particular moments and to relish them. And then you move along, and then you go deeply into another moment and you relish that and you roll it around on your tongue, metaphorically. Then you move on to something else.

I think students reading Shakuntala should know that they should stop and relish each moment for what it is, and think about the ramifications. In other words, I always think if you start creating associations as you read Shakuntala, that's what a performance of Sanskrit drama would be designed to do as well. Rather than sort of reading across the text, you want to get to a particular moment and then start daydreaming, having all of your emotional and political and social associations with that moment.

Michael: Kutiyattam sounds like a fascinating and complicated performance tradition. I'm curious how is it performed today, and does the way that it's performed today reflect any changes in modern India?

Erin: Well, it's performed in a number of different ways. There are still performances that last forty-one nights. They happen in temples, etc. there are performances on proscenium stages. There are performances that last for five days in temples. There are what I call tourist performances, some of which are about an hour long. There are performances that are what I would call excerpts of kutiyattam of particular scenes or moments that might last three hours. You can still see an evening of kutiyattam where the performers are elaborating on three lines of text, so you're not then seeing "the whole play", but you're seeing a traditional mode of elaboration on three or four lines of text.

Kutiyattam is then performed in what I would call secular situations on proscenium stages, as part of festivals, etc. There are adaptations of kutiyattam that have been performed, and [Ji Veno 00:32:00] has a two-hour version of the play Shakuntala. Now, if you're used to a forty-one nights version of kutiyattam, you can imagine that the two-hour version might feel incredibly different, so purists in Kerala will say that this is really no longer kutiyattam. It might be performed by someone who's trained in kutiyattam, someone who identifies as a kutiyattam performer, but if you don't have the elaboration, you're not really doing kutiyattam.

Others might say that if you're not performing it in a temple or as an offering to the deity, you're not really performing kutiyattam. Others might argue that if you have eliminated the vidushaka, the clown character, and if the play is not translated both literally and metaphorically, and the connections are not being made to the audience, then it's not kutiyattam. But I think that kutiyattam as a genre can stand to include the large number of manifestations of it that exist.

Michael: We'll post images and video of kutiyattam performances in our show notes. Join me and Erin next week when we'll discuss how theatre has changed in modern India.

Erin, thank you so much.

Erin: Michael, thank you so much.

Michael: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit HowlRound.com, and follow HowlRound and @theatrehistory on Twitter and Facebook. You can also visit our website at theatrehistorypodcast.net. Big thank you to the staff at HowlRound who make this show possible. Our music this week comes from the Center for Excellence in Kutiyattam. Thanks as well to Tim Cress, who designed our logo. Finally, thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here