Transcript:

Michael Luegar: The Theatre History Podcast is supported by HowlRound, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. It's available on iTunes, Google Play, and howlround.com.

Hi. Welcome to the Theatre History Podcast. I'm Mike Lueger. "Freak show" is a term with some ugly historical and cultural resonances today. But in the nineteenth century it was an immensely popular form of entertainment. Dr. Matt DiCintio has been studying the freak show, particularly in the context of its eighteenth-century origins and its relation to race. He joins us on the show today.

Matt, thank you so much for being with us.

Matt DiCintio: Thanks a lot.

Michael: First off, what was the freak show, and what do we mean when we use that term "freak"?

Matt: I think it's important to understand that any time a historian uses the term "freak show", we should understand the word "freak" to be in quotation marks. And so of course the word does indeed have a negative connotation. Historians use it as shorthand for the display of any person who had any sort of biological or physiological difference, anomaly, anything about their body that was different than what this historian Rosemarie Garland-Thompson referred to as people who are "normates", so people who have expected quote, unquote "normal" bodies. And people who have had different bodies have been on display for millennia. The Romans made "dwarfs" quote, unquote, so little persons fight in the Coliseum, and the tradition continues up to this day with any sort of show you might prefer on TLC, whether it's "My 600 Pound Life" or "The Little Couple", or there are many others. So the interest sometimes prurient, sometimes sexual of seeing people with different bodies has been a hallmark of human curiosity for millennia.

Michael: Now, we're talking about the end of the eighteenth century and going into the nineteenth century. What kind of cultural and intellectual things were happening in that period that helps to give rise to the freak show?

Matt: I study specifically early America. The early eighteenth century, of course, was when the colonies became the United States. Throughout the eighteenth century, irrespective of the founding of the United States, there was great anxiety among people living in the colonies, living in America, about what kind of world they were living in. There were many European "natural philosophers", as they were called then, who assumed and wrote extensively about the idea that the climate of North America was deleterious to the human condition. The French natural philosopher the Count de Buffon spent fifty years publishing volume after volume about how the climate of North America was dangerous. And so there was great anxiety about these people living in America about what kind of world they were living in.

Of course, when I say "those people", I'm talking about the white people. And anytime there was any sort of Native American encounter or insurrection or battle, that only enhanced the idea among British Americans, primarily, that the world they were living in was not safe. It reached comical proportions. There's a great little book by a historian, Lee Dugatkin, I believe is his name, about the attempts and the lengths to which Thomas Jefferson went to prove that the North American climate was in fact not harmful. He went to great lengths to find the largest moose that he could to send to France to the Count de Buffon to prove that, basically, "Look how big this moose is. Told you it's not dangerous here and that the climate is not harmful to us." And the story about how the moose was lost, he was found again, I mean it was farcical. The punchline is, Buffon never recorded his reaction to it.

And in part this was what partly fueled the expedition that he sends Lewis and Clarke on. It was not only to discover the land, but also in his instructions to them he was greatly concerned about whether they would find giants somewhere in the middle of America. As the eighteenth century rolled on and you get into questions about American independence, this only more greatly enhanced the anxiety about what kind of world are we going to live in, what kind of people are we going to become. Thomas Paine famously asked, "Are we going to be a nation of white men or of black men?"

So in an attempt to exorcize that anxiety, the ability to see other people who were "not like them", quote, unquote, was a way of working out that anxiety. If they could see a freak, they could reassure themselves that they were in fact on the right track. As many historians have noted, this was also the underlying urge that spurred Victorian era freak shows as the middle class rose and as people were looking for ways to coalesce and identify themselves as something and using the other as the marker of what they were not.

Michael: You've mentioned sort of this role that race plays. It sounds like it's kind of always lurking there as a factor in the popularity of the freak show. Could you tell us a little bit more about the specifics of that? In particular, can you tell us the story of a man named Harry Moss?

Matt: Sure. There was great anxiety as the nation was founded about who would be counted as Americans. And of course there was great consternation about what to do with the slave population and with the presence of black men, women, and children who were not slaves, and what kind of population America would have. Right, this is how we get that three-fifths compromise. Right? To be sure, it's not that black men, women, and children, and slaves were counted as three-fifths a person, it was three-fifths the population for the purposes of apportioning representation.

So there was great anxiety about what to do with the black population. And there were many, many, many people who wrote about this. Thomas Jefferson, perhaps most famously in his Notes on the State of Virginia from 1780-'81, pondered this and came down with the idea that, yes, we should free them, but basically, are they smart enough to live on their own. By keeping them as slaves are we doing them a service? So these are obviously white supremacist strategies. And there were events throughout particularly the late eighteenth century that exacerbated these anxieties: The slave uprisings in the Caribbean brought more quote, unquote, "colored bodies" into America, particularly in large cities like Philadelphia.

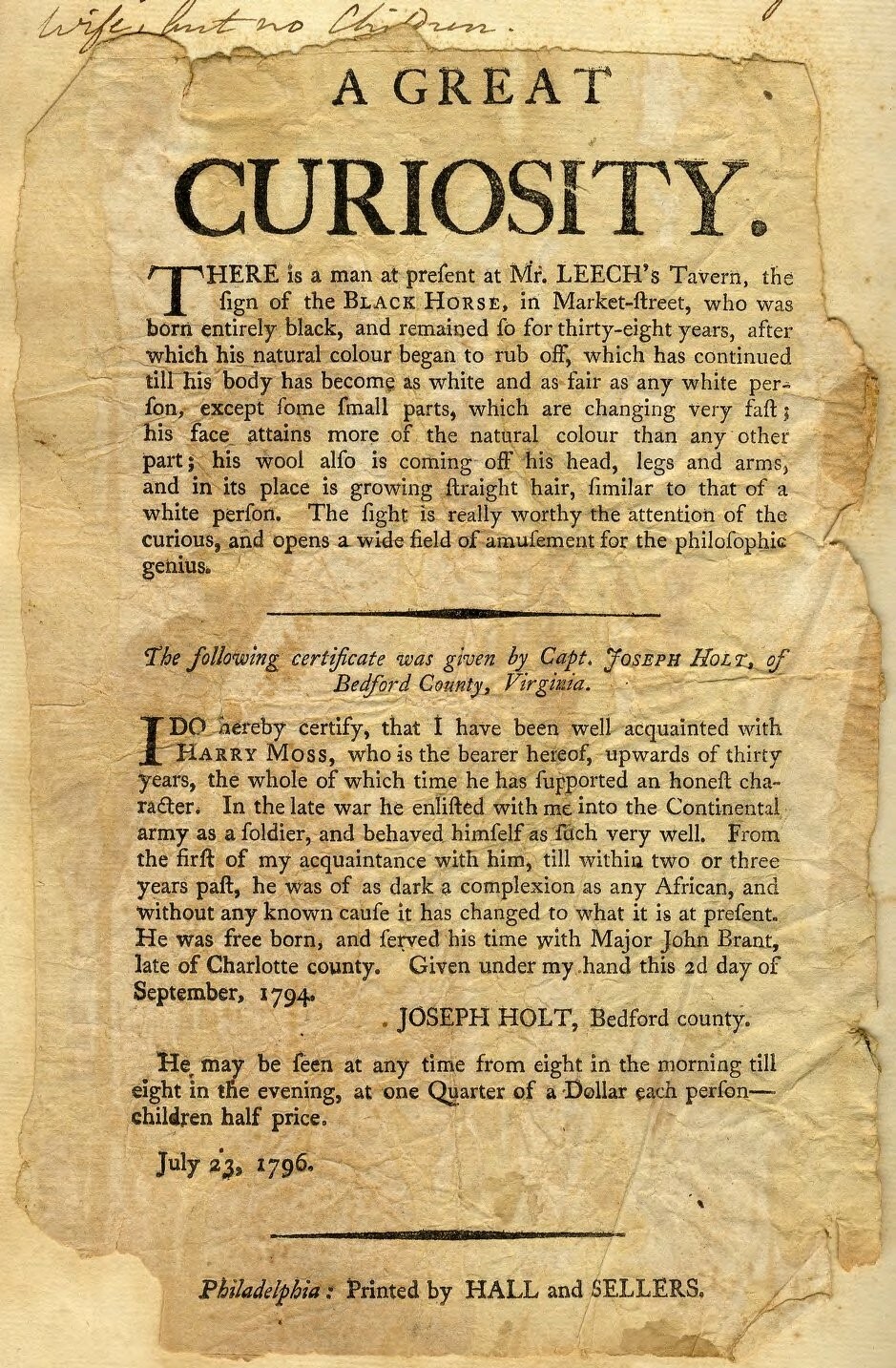

So among all this in the mid 1790s, Harry Moss put himself on display at a tavern in Philadelphia. Harry Moss was a native from Virginia. He was a freeman, and he had what we would likely diagnose today as a form of vitiligo, so a pigment deficient condition where dark skin begins to turn white in patches on the body, if not completely. So he put himself on display as a freak. He was among one of the most famous, probably the most famous of what they at the time called "white Negros". There was a substantial interest in the eighteenth century in white Negros, so black men, women, and children who either had vitiligo or were albino. This was not limited to America, all across the west.

So he put himself on display and many, many people wrote about him and went to see him, paying him to see him, touch him, feel his skin, make observations about what his skin looked like, what kind of family background he came from. He was of mixed heritage. The reports vary, but he may have come from grandparents who were Native American, perhaps Irish. It's not clear, the reports vary, but he did have skin as a black man that was beginning to turn white. As people went and visited him and spoke to him, they of course remarked on how articulate he was.

The fascinating thing about his display is that unlike many other freaks of the era and subsequently, most notable PT Barnum, Harry Moss did not have a handler. He was not managed by anybody. He put himself on display, charged admission, probably splitting it with the tavern owner, and let people talk with him, touch him, examine his body, his black body that was turning white, and took their money. One doctor who examined him and interviewed him made many observations about his sex life. He questioned him about the smell of his urine. He questioned him about when he got up in the morning, did any of his blackness rub off on the sheets. It did not, and apparently his urine smelled fine. But people, abolitionists in particular, were very taken with this. One person explicitly noted, "If it's so easy for Harry Moss to turn white, why would it be so difficult for us to turn black?"

So Harry Moss's appearance in Philadelphia, and all the accounts about him were really this flashpoint about questions about what kind of nation were we going to become, and who were we going to count as citizens of the new republic. What's all the more remarkable about his display was that the tavern was right around the corner from the London Coffee House, which was Philadelphia's slave market. When potential owners would go to a slave market, they would examine slaves quite in depth in terms of their behavior, but also their physical health and would inspect them in ways that were quite intrusive. The preference for slave owners was that their slaves be as black as possible. They believed that the darker the skin, the more healthy they would be, the better worker they would be.

So while this was taking place, around the corner Harry Moss was putting himself on display and submitting himself to physical examinations that were not all that different from how slaves would be examined. So it's just really remarkable summer in the 1790s when this one man who put himself on display really served as a focal point for anxiety about the racial makeup of the early United States.

Michael: Another instance of an individual whose race factors into her prominence in a freak show is somebody named Saartjie Baartman. I was wondering why was her time being displayed as the so called "Venus Hottentot" so important to the development of the freak show?

Matt: We often look at Baartman's exhibition as what really inaugurated the nineteenth century craze for freak shows. She was from South Africa. She was brought to London in 1810 and put on display, and by all accounts had a completely miserable life. Susan-Lori Parks has written a lovely play about this called Venus. What's remarkable about Baartman is that we don't even know that that's her real name. We actually don't know what her real name was. Saartjie Baartman is a sort of British English bastardization of what it could have been. So she died shortly thereafter. For the next two centuries she was on display. She had an autopsy, and then her body was on display, and then her skeleton was on display into the twentieth century. I believe it was in 2000 ... I don't know, about ten years ago, I don't quite remember the date, the French museum that housed her, held her body, finally sent her back to South Africa where she was interred.

So her display in 1810 and the few years after, really inaugurated what was the ... Oh, hesitate to say, golden era ... but I think your audience will understand what I mean ... of freak shows. Not long after, PT Barnum rose to prominence when he displayed a slave by the name of Joyce Heff, who he claimed was 180 years old and was George Washington's nurse. So that's how he originally came to fame.

Then thereafter as Barnum collected more and more people who were physically different, and many others did too, the freak show really became this venue where people in increasingly urbanized places could go and coalesce as white people seeing something different and therefore knowing that they were gonna be okay. And many of them had miserable lives. Many of them became quite wealthy and certainly quite famous by their exhibitions.

Charles Stratton, who is remembered as Tom Thumb, became incredibly famous. He was a little person. His visit to meet the queen of England was covered around the world. His wedding to another little person was on the cover of I think it was Harper's during the Civil War. Their wedding bumped the war off the front page. So they became incredibly famous, very wealthy, and many of them quite miserable by the end of their lives. There were many little people that PT Barnum displayed who wound up just drinking themselves to death. They all had names like General Stratton. So Tom Thumb was General Tom Thumb. There was a Major Moat, and there was a Major Adam, right, all these superlatives coupled with their smallness.

Michael: You also write about an individual named Emma Leach. Can you tell us about her and why you set up a little bit of a contrast between her and Baartman?

Matt: Sure. Emma Leach was a woman with some form of dwarfism. She was called the Maiden Dwarf in accounts of the time. She appeared once in Boston in 1782 and was reported on widely. There's a very famous picture of her, an engraving of her, that graced the cover of several almanacs of the time. People originally thought that Paul Revere did the engraving, he did not. But she was on display once in Boston in 1782, and people were very, very fascinated with her. It's dangerous to diagnose in hindsight, but she had several ailments. She couldn't walk, she had to be carried. She had some complications with the alignment of her spine, so her chin was very close to her chest, so she could not articulate very well. But she was apparently quite a character and would love to tease the people who went to see her. She was on display in the home of a woman, of a widow, and people would go and pay their entrance fee, half price for children, to go and look at her and try to converse with her.

The most extensive account about her talks about how ornery she could be during her presentations, but also notes that the author of that article apologizes to his readers that he could not offer as many details about her as they may want because she would not allow a minute examination, which probably means she wouldn't take her clothes off to let them investigate her genitals. This represents one of the pervasive questions about freak shows. There's a scholar by the name of Elizabeth [00:16:44], who wrote about the sex lives of freaks, that what we want to know is how do they do it. So it's no mistake that they refer to her as the Maiden Dwarf.

One of the issues with thinking about and talking about freak shows certainly with the rise of disability studies in the past several decades has been the issue of is there any way in which the freaks were able to find agency in their performances. Was there any way that they were able to do something more than get stared at? Was there any way in which they were able to stare back? So I'm fascinated with Emma Leach because I think that her refusal to let them all know everything that they wanted to know was her way of saying, "No. This is the one thing that I get to have control over." After her exhibition in Boston, she retired home to her small town in Massachusetts and was never on display again. She never appears in the archive again until her death several years later.

I did do some noodling around on Ancestry.com, which is how I found her family's death records. We all thought that she only appeared once in Boston in 1782, but newspapers misspelled her last name and they misspelled her first name, perhaps because she couldn't pronounce her name fully. She was on display once before in Salem in 1781 and was only there for a brief time. There's no indication about why she appeared there and why she appeared again in 1782 in Boston. THere's a reference to gentlemen convincing her, but the distinction I draw between her and Baartman is that at some point Emma Leach decided and had the power to decide that she was not interested in being stared at. Baartman really didn't have that option. It's also worth pointing out that Baartman was black, and Emma Leach was white.

Michael: What happened to the freak show, and in what ways does the freak show continue to influence the ways that we think about disability, physical difference, perhaps race, even to this day?

Matt: Scholars of freak shows point to the 1950s, right, where freak shows had their demise because basically the public got a conscience and thought maybe this wasn't a good idea. There are freak shows that still exist. Famously there is one in Venice Beach. There are many fairs that continue to have freak shows. I've been to several. Mostly, though, they're fake. The mermaid I saw, I don't believe was real mermaid, and many of the freak shows feature people who can do amazing acts and are not people who have some sort of physical difference that we can gawk at.

That being said, as we ... I mentioned TLC earlier. It's on TLC that we continue to see the freak show in all its traditional complications. The thing I show my students when I teach this is there's a clip from The Little Couple, which is a show several seasons long, I believe it's ended now, about a couple. They're little people and they have adopted children who are also little people. The show follows them throughout their normal lives. The wife has cancer at some point. The husband has a lot of physical problems that accompany people with dwarfism, a lot of back issues, so it follows them through their surgeries.

But there's one episode where the family is doing nothing but practicing a fire drill. People going through surgeries like back problems and cancer, those are TV shows that we've seen before. That was, you know, TLC did that when it was called the Learning Channel. But there's this episode where this couple, where this family is practicing a fire drill. There's absolutely nothing about it that is in any way extraordinary or in any way different than any family may practice a fire drill, except they're little people.

So the freak show is alive and well. We just don't call it that anymore. Right? As I mentioned somewhere around the 1940, '50s, the public got a conscience and thought maybe we shouldn't stare at people. We still stare at people, and what the freak show demonstrates is that we are both extremely compelled by people with physical difference ... and by "we" I mean normates, people who are not marked by physical difference ... so we are extremely compelled by then. On the other hand at the same time, it is really, really easy to forget them. So it's easy to turn of TLC after you've enjoyed your two hour special of My 600 Pound Life. It was easy to go to the freak show to see Fedor Jeftichew, who went by Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy. He had hypertrichosis, I believe, so excessive hair. Or to go see, you know, the Bearded Lady, and then to go home, having been entertained, and forget about it.

This dual notion of both being compelled and having amnesia persists today. The movie The Greatest Showman does this extraordinarily and, unfortunately, very well. So set aside the historical inaccuracies, and the movie of course completely ignores Barnum's rise to prominence by crating a slave woman around the country. And okay, fine, we can get our dander up about historical inaccuracies, and we should. What concerned me most about the film was, it's entertaining as hell, and on the other hand you watch the credits roll, and all of the freaks who are in the freak show, we know who they are, we know their names and they are listed in the credits only as dancer oddity or human oddity. They never name them beyond Stratton, beyond Tom Thumb. I was stunned that they would do that. These were very famous people, it's not hard to find out who they were, it's on Wikipedia for God's sake. So the simultaneous ability to be compelled by freaks and to utterly forget them ...

A great example of this in the ongoing debate about the elimination of plastic straws. So yeah, it's great to eliminate plastic straws in an attempt to protect the environment, but what a lot of people who are behind these campaigns forget is that a lot of people need straws in order to be able to drink, because of different physical conditions that they may have. There are issues with ... get on my little high horse here ... there are issues with straws that are not plastic that people with some physical conditions cannot handle: Pasta, straws, paper straws, can cause choking. Glass straws can be dangerous. So plastic straws can really be the only other option, and we forget about that when we have conversations about let's protect the environment and get rid of plastic straws.

People may counter with, okay, (1) can't they carry their own straws? So, okay, now they have to do something else for our benefit. (2) Can't they ask for one? They can, and then mark themselves again as other. So even in debates where many of us could agree let's get rid of plastic straws, we forget how ableist we can be. It's really easy to forget people with physical difference, no matter how much we are entertained by them.

Michael: We'll post additional resources in our show notes that will let you explore the freak show and how nineteenth century audiences encountered and thought of physical difference. Matt, thank you so much for explaining some of the complicated history and cultural dynamics of the freak show to us.

Matt: Thank you, Mike.

Michael: If you'd like to continue today's conversation, please visit howlround.com and follow HowlRound and @theatrehistory on Twitter and Facebook. You can also visit our website at theatrehistorypodcast.net where you can find links to all of our episodes. You can email your questions and comments about the show to theatrehistory@theatrehistorypodcast.net.

A big thank you to the staff at HowlRound, who make this show possible. Our theme music is "The Black Crook Galop", which comes to us courtesy of the New York Public Library Libretto Project and Adam Roberts. Thanks as well to Tip [Kress 00:25:23], who designed our logo. Finally, thank you for listening.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here