Tobi Kyeremateng: I thought it would be interesting to have this intergenerational dialogue about performance and activism in the UK—I’m a younger and very London-based producer, and you have more years behind you, and a wider sense of the UK, as an internationally renowned poet. What did things look like back when you were starting out, how have they evolved, and what does it look like now?

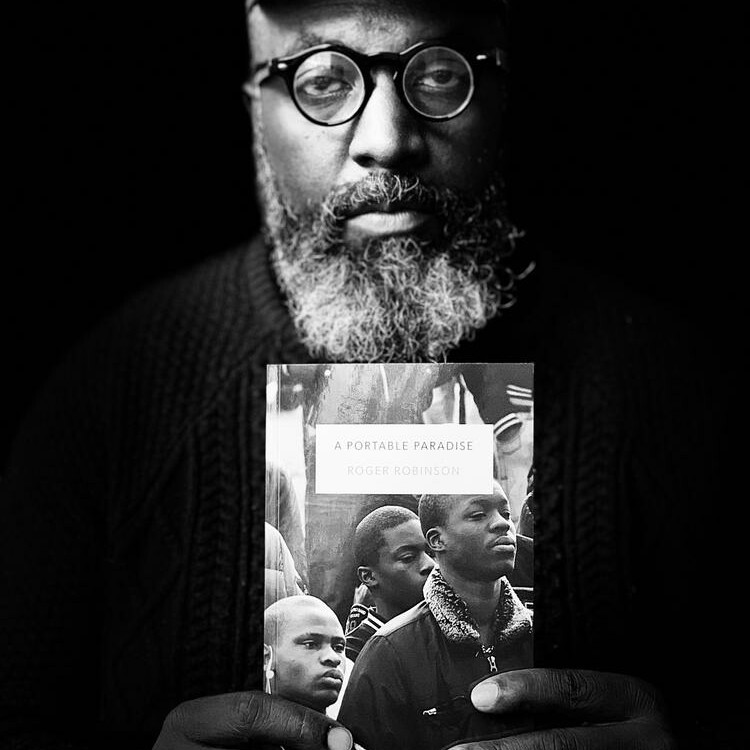

Roger Robinson: I’m celebrating twenty-five years of performing on a professional level. When I first started, Black writers and performers were literally invisible. People knew you in a small, small scene. You could be very popular there, but on a national and international level, Black writers and performers were invisible.

Somebody could come to the UK from America and they’d be like, “Do they have any Black people here?” Cause you couldn’t tell from the literature or from the shows. And even when Black people had shows, the shows didn’t necessarily represent Black people. Oftentimes they just reiterated the status quo of middle-class white men. Those were the ones that were allowed to trickle in. Not any show that was particularly Black or Black-space oriented or Black-life oriented. Cause nobody twenty-five years ago wanted to hear about Black life. It wasn’t a thing.

Here’s an example. Twenty-five years ago I was trying to look for a mentor. The few people who were Black, who worked in universities, were like: “No, absolutely not. Please don’t contact me again.” That generation before me was hard core! I kind of understand it now, as time has gone on, because they had to fight and struggle for every little thing they got. They didn’t have time to mentor anybody else. It’s not that they hated other Black people, but their concern was: “It’s hard enough for me to be in white society and try to do well.” Like, “I don’t have time.”

It’s not that I blame them. In fact, it definitely gave me—along with some of the other writers I was around, like Malika Booker—a sense of why it was necessary to get some type of creative citizenship. That’s the name we give it now, but back then we weren’t thinking about it. We just wanted to create a community. And if we knew anything, to pass it on to younger writers. That’s something that we did—Malika in particular, me, and some other writers who came under us, like Nick Makoha, Jacob Sam La Roses, and Rachel Long. We passed it on. It was an unwritten pact. Because the only thing Black writers really have is their relationships. The Black writer has never been about major money. It’s always been about relationships and the world.

For the people who were sharing the information, certain communities and bonds were built. That was such a big part of the politics of Black writing and Black success in England, much more so than funding or anything like that. The funding never really promoted anything that was long lasting. You’re a good, young producer, but I bet you can’t name ten Black shows from the eighties.

Tobi: No.

Roger: It’s not because the work wasn’t good. It’s because it was set up for it not to be resonant. Whereas in your time—the kind of things you’re doing now—you still have to struggle and you still have to fight, because the upper echelons of theatre are run by the same people. Nobody wants to say it, but theatre is built on status quo, and all the audiences are mostly middle-class white people. Middle-class white people who, to be honest, don’t really care about anybody else’s story. How do you break that?

Creative citizenship is looking at how to be a citizen with your art and debunking old state ideas and clichéd ideas of being a success.

Tobi: I want to go back to creative citizenship. Can you expand on that? I find that really interesting.

Roger: Creative citizenship is looking at how to be a citizen with your art and debunking old state ideas and clichéd ideas of being a success. Back in the day, when people wouldn’t put us on, we put ourselves on. All these shows that we used to do—for the first two or three years they were in venues only on Wednesday nights in the West End. We used to use this place called the Spot all the time. We got a mic and everything for free. Some of those shows were the shows that moved theatre forward.

Everybody was really interested in theatre combined with spoken word. We’d have two hundred people and up, all the time, because there was nothing else for them to see in the theatre. That was a form of creative citizenship: “We are going to put ourselves on. We are not gonna wait for anybody to call us. We are gonna provide for the underserved community.”

We always had that type of attitude. There was a point when we were so influential that a white establishment called us because we had crowds of people. We’d sell out all the house three nights in a row.

Two important links in this chain are Bernardine Evaristo and Kwame Dawes. They were a big part in the whole idea of setting up creative citizenship, even though they didn’t call it that. Kwame agreed to mentor me from Nebraska. Bernardine had brought him across to the UK to teach. We would get all the Black writers together and tell them they could come and do workshops at Spread The Word, which was in Brixton at the time, before it moved to Deptford. It was a whole bunch of Black writers, like me, like Malika, and a lot of people who probably don’t write anymore, actually. Bernardine knew that we had talent but didn’t have money to take courses.

Kwame spotted talent, he would say, “Send me the work! How can we help you promote yourself?” and “I just need you to pass it on, so make sure what I teach you, you’re teaching somebody else.” That started influencing Malika’s Poetry Kitchen, a collective of predominantly Black poets, which went on for twenty-one years or so. When we started it, it definitely was something. We never got paid for it or anything like that. From Malika’s Kitchen I started something at Theatre Royal Stratford East in London called Spoke-Lab. Which was again unpaid. I just wanted to get Black people—specifically those who did spoken word—into the theatre. Spoke-Lab ran for about two and a half years, every single week. Inua Ellams came for two years, every week, and the word broke out.

We would meet thirteen or fourteen times a year and hash out how to make this interesting. It was an experimental space. That’s another thing Black people don’t have, especially in theatre. A space where people can try things and fail. Theatre is hard. Lots of people who weren’t serious came and were like “Eh, yeah I’m not sure if I’m cut out for this.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here