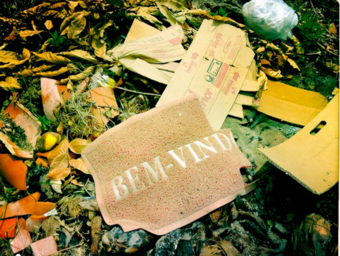

The group planted and then harvested for long hours. There were ritualistic moments that involved an exchange of experiences, eating together, resting—a series of actions that did away with individualism and the rushed timelines of capitalist productivity. The performance did not abandon routine or intend to create an extraordinary event. It was not only for homogeneous group, and it did not intend to shock or create an uncomfortable experience. The performance simply established a new daily routine, profound and simple, communal and diverse, engaged and affectionate. A welcoming spirit permeated the whole experience.

Yes, but welcoming of what? “Umuarama” suggested that spaces such as cities could welcome greater biological diversity and complexity. They could create routines that break the violence and logic of western mercantilism and individualism and that reestablish a connection with other possibilities of being.

“Umuarama,” in my opinion, is a work that opens possibilities for experimenting with creating a new routine in the hearts of the machine-like urban labyrinths of our consumerist and extractive societies. Each alternative routine spreads hope and hacks the system.

It is the obligation of the culturally white (myself included) to denounce and deconstruct this pedestal that colonization and racism has put under our feet.

This experimentation resonates with the concept of porosity—an idea originated by Walter Benjamin and revisited by Ernst Bloch, Mássimo Cacciari, and urban planner Bernardo Secchi, among others. Porosity disrupts the homogenizing of cities by embracing the multiplicity of lives within them: the lives of those elements that support them, the soil that feeds them, and all of their interactions with their environments. Porosity in cities allows for exchanges between subjects of different classes or species, seeking to respect mutual rights. It is the opposite of establishing barriers, walls, or sieges. In Eduardo Sombini’s recent interview with Italian architect and urbanist Paola Viganò, the architect states, “Each city, large or small, can participate and be part of this experiment… It is possible to imagine a capillarity with regard to relationships with non-human components, in which the key is to look at the whole territory as a being and inhabited by other beings. We must see them [non-humans] as beings. When you do that your point of view has already shifted.”

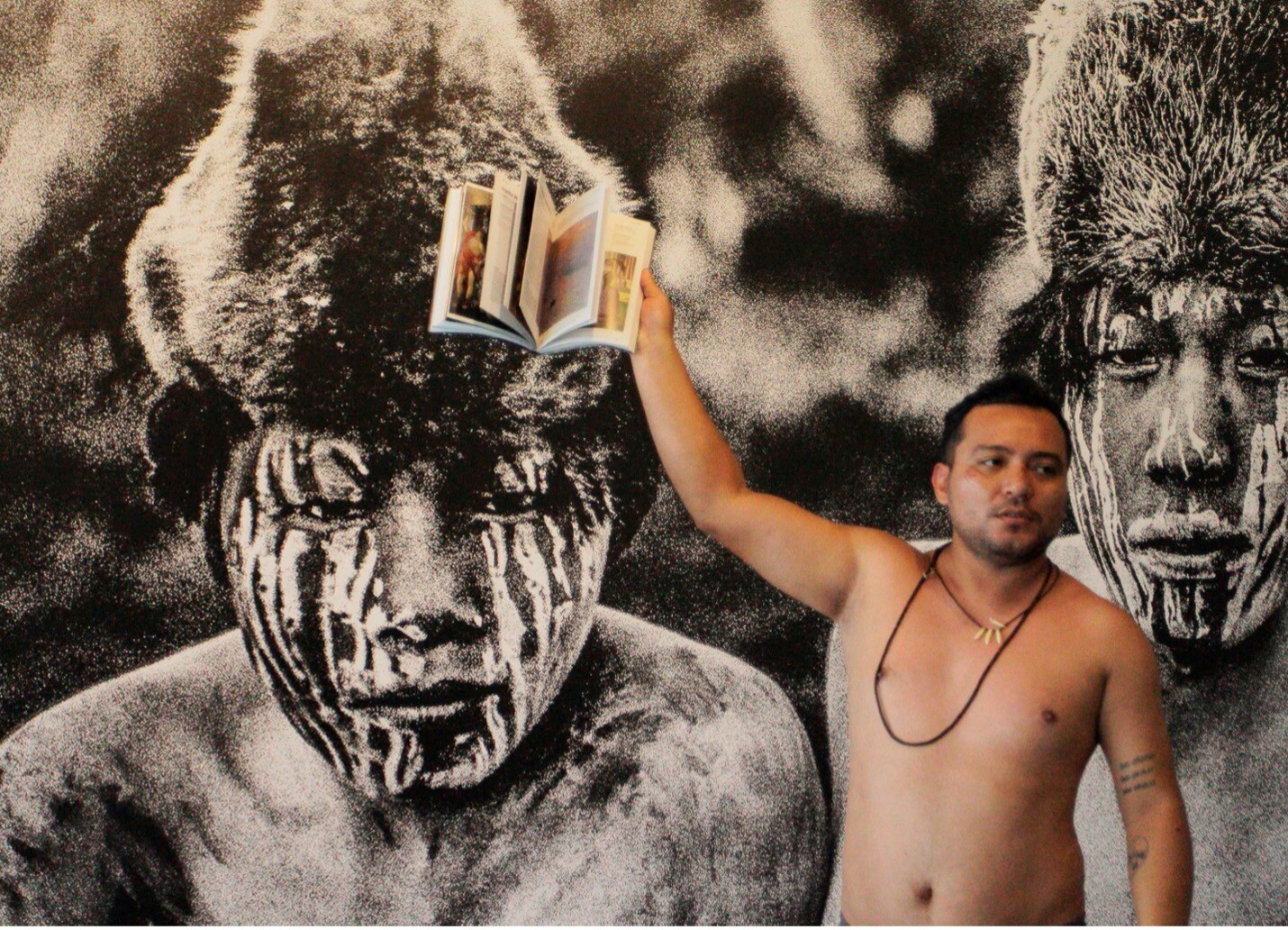

This means a new paradigm for Europe. From non-European perspectives, the paradigm is nothing new, though those operating in this way were the object of colonization in Africa, in Asia, and in the Americas. In the words of Ailton Krenak, a Brazilian environmentalist, philosopher, poet, and writer from the Crenaque Tribe, “when we depersonalized the river, the mountain, when we take their meaning from them, their sense, thinking that such things are uniquely human, we release these places so they become residues of industrial and extractive activity. Our divorce from integrations and interactions with our Mother Earth results in us becoming orphans, not only those of us who, at different levels, are called indigenous peoples, but all of us.”

This divorce manifests in the way big cities are built, in the way things are produced and consumed, in the predatory use of technologies and of knowledge, and in the violent deletion of everything that exists outside the neoliberal logic of competition, of individualism, and of the haste associated with consumerism and productivity. Nothing can be free, slow, useless, everlasting, simply beautiful, or spiritual. Everything becomes a commodity. One of the largest Chinese commercial companies launched a facial recognition app called Smile To Pay, which allows people to make purchases with a smile. The face, the most sacred manifestation of our human singularity, becomes a credit card. The smile, the most generous and subtle of expressions and of our infinite emotions, becomes a password to authorize payments. The logic of capitalism continues to commercialize every relationship with the world and beings both human and non-human.

“Memories of a Former River” by Gabriela Holanda

"Porosity is related to the ability of liquids to infiltrate rocks, depending on their type. Hence, we speak of social porosity, imagining cities where the relationship between different groups can be fluid. What we increasingly see in cities is a reduction in porosity and very difficult flows and exchanges between parts of the population. It is possible to imagine porosity in terms of relations with the non-human component, in which the fundamental thing is to look at the entire territory as a subject and inhabited by subjects. You need to see them [non-humans] as subjects. When you do that, your point of view has already changed. I consider water a subject, for example. The rationality of water in the city has to be understood, not only as a functional element that you can redefine as you wish, but as a subject that is bringing its own way of thinking and its own behavior." Say Paola Viganò in the aforementioned interview. In few words: Porosity implies allowing exchanges between subjects of different classes or species, seeking to respect mutual rights and respect. it is the opposite of establishing barriers, walls, sieges.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here