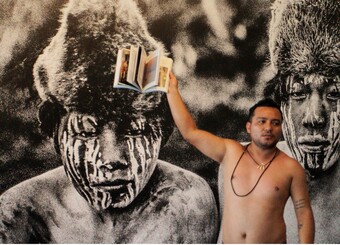

Through connection with these elements of Black cultural identity and immersion in Black ancestral values, the individual immersed in this experience “Blackens” metaphorically and socially—that is, activates their connection with their Black African descendent identity. Straddling the worlds of Candomblé and theatre, I have been developing a deep poetic process of eco-reconnection through my scenic practice. Teatro Preto do Candomblé uses a theatrical and lyrical approach developed through the scenic research method Ativação do Movimento Ancestral (Ancestral Movement Activation). It affords eco-reconnection between the individual and the environment.

The actors form a community incited and inspired by the ethics of Candomblé. The immersion into the terreiro shows the actors another type of social existence that both the original peoples of Brazil and the pre-colonial Africans enjoyed: their relationship with nature and their daily life was one and the same. Eco-reconnection consists of an actor and scenic action that takes our planet’s environmental reality as a daily theme for reflection, problematization, and artistic creation.

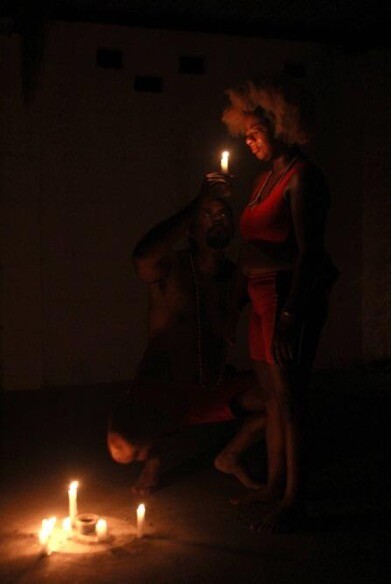

Besides connecting the actors with their African ancestry, Teatro Preto do Candomblé invites them to assume a more positive and less destructive attitude in their relationship with the environment where they live. This is a scenic-sensory-spiritual immersion that uses ceremonies for the construction of the scenic action. Organized and overseen by the yalorixá Mãe Rosa de Oyá and me, the ceremonies range from ritual offerings to energizing baths and requests for authorization of divinities and/or ancestors to carry out scenic improvisations through the intimate contact of the actors with the four essential elements of nature.

After organizing the deities according to their predominant nature element, we salute them liturgically and scenically in four rituals: fire ritual (Exu and Xangô), earth ritual (Ogun, Oxossi, Omolú, Ossãe, Obá, Iroko and Logunedé), ritual of air (Oyá, Oxumarê, Ewá and Oxalá), and water ritual (Oxum, Yemanjá, Logunedé, Ibeji and Nanã). The objective is to put the actors in contact with the energies, colors, music, dances, foods, aromas, textures, sacred signs and legends of each of these orixás and with the energetic emanations of each primordial element. Through this Afro-scenic-poetic immersion, the performer establishes contact with the divinities and the images and sensations derived from it to generate raw material for the scenic construction, alongside the reflection on ethical, liturgical, historiographical issues that yield materials for the performance and staging. The initiation rituals bring the actors into contact with the past, family and mythical memories; and lead the ori-ara-emí (head-body-spirit) to the dimension of spirituality, ancestry and nature.

Besides providing a closer contact with the daily activities of the terreiro, this immersion allows the actors to observe and learn about the cosmogony of the ancestral African and Afro-Brazilian cultures and establish a contact with the deity in question. The goal is to connect the actors with the energies, colors, music, food, and legends of each one of these orishas, as well as with the energetic reverberations of the element present in the personality of each deity. Through this process, actors are filled with images and sensations that are the raw material for scenic construction.

Once the priming activities establish the context of the research, we can them bring it into the rehearsal room, where we further discuss ethical and liturgical issues. These priming rituals served as launch pad in the methodology for the actor’s physical conditioning that we call bodily temple. This is a notion of a sacred body, a divine abode, a living altar where the presence of the orishas can be summoned. The elders of the axé introduced me to this definition of body during my earlier schooling into Candomblé. It was academically coined by Ana Claudia Moraes de Carvalho in her article “Corpo-encostado.” The bodily temple, in the religious sense, is the body filled with the cosmic forces in close contact with the divine, in deep eco-reconnection. In the theatrical sense, it is a body overtaken, connected to its ancestral roots, aware of a cultural identity, and in a state of readiness. This forms the actor’s “scenic self”—or their identity on stage—an element also present in Eugênio Barba’s Theatre Anthropology. Teatro Preto do Candomblé situates the search for this scenic self inside of Candomblé’s universe to create performance exercises that bolster the actors’ energetic creativity and their performative presence while strengthening the relationship between Candomblé and Theatre.

I have been developing this work in search of eco-reconnection, Black ancestry, and affirmation of the three important fields—Candomblé, theatre, and ecology—for a qualitative change in our societal construct and rights. This three-pronged consciousness provides training and ethics based on those of the original peoples of Brazil and of those inherited from the African peoples we keep alive in each ceremony performed in the axé communities. May the theatre, our restless art, with its powerful possibilities for meetings, reflection, and problematization, add to its repertoire such creative processes and performances that lead us to eco-reconnect.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here